Cinema’s ultimate scene-stealers

In a landmark 2009 essay, the influential author John Berger argued that capitalist societies had commodified images of animals, reducing them to pictures of innocence. In our daily lives, he wrote, animals had been consigned to the realms of family or spectacle – most obviously, as pets or in zoos.

EO, the latest feature from the Polish filmmaker Jerzy Skolimowski, departs from the historically showy, contrived and stunt-packed performances of animals in cinema, from the early caper Bout de Zan Vole un Eléphant (1913), in which a child steals an elephant from a circus, to Fearless Fagan (1952), where a newly enlisted soldier brings his pet lion to the barracks. In his understated and yet emotionally devastating new film, Skolimowski, director of Le Départ (1967), creates instead a more subtly crafted portrayal of an animal’s experience. With shots that linger on EO’s pensive, wistful eyes and shot-reverse-shots that capture his gaze, the film makes a blisteringly compelling case for what it might be like to experience the world as a donkey.

More like this:

– 11 films to watch this February

– Films that scare in unexplainable ways

– The dark side of a children’s classic

EO begins as a circus goes bankrupt and its show animals are bundled into trucks, while a protest about animal welfare swarms portentously around them. From that point on, EO the donkey is passed around a flurry of handlers: illegal horsemeat traders, fox breeders, and an ex-trainee priest (Lorenzo Zurzolo) who tells EO that he has eaten salami “made with donkey meat”. In the interludes where he briefly breaks free, EO trots on, in hope of eventually returning home to his affectionate trainer, Kasandra (Sandra Drzymalska). “I treated human stories as much less important,” Skolimowski tells BBC Culture. “I practically reduced them to vignettes. The stories I was telling about those few people were not exciting – they are typical human situations, where [the actors] demonstrate the most typical human behaviour and moods: anger, love, the need for revenge. I only gave the minimum amount of information to the audience because they read between the lines. For me, the donkey – his reactions, his comments in those huge melancholic eyes – was the most important element of the whole film.”

EO makes a compelling case for what it might be like to experience the world as a donkey (Credit: Skopia Film)

Over the past decade, filmmakers – particularly in documentary – have looked beyond the human, foregrounding animals’ stories and perspectives. Kedi (2016) and Stray (2020) followed vagrant cats and dogs respectively, as they roamed the streets of Istanbul, attempting to carve out space for themselves within the rough-and-tumble metropolis. Bartek Konopka’s Rabbit à la Berlin (2009) was vaunted for showing a brand-new perspective on the fall of the Berlin Wall – through the eyes of the rabbits that lived quietly, mostly free from human conflict, in the zone between East and West Germany. Denis Coté’s Bestiaire (2012) observed the relationship between the captive animal and the human gaze, Emmanuel Gras’s Bovines ou la Vraie Vie des Vaches (A Cow’s Life, 2011), looked at the inner lives of livestock, and Victor Kossakovsky’s wordless barnyard-set documentary Gunda (2021) focused on a mother pig. British director Andrea Arnold’s first feature-length documentary Cow (2021) was about “show[ing] the aliveness of a nonhuman animal,” she told Vulture. “Our relationship with the millions of non-human lives we use is very much part of our existence. I made Cow to invite engagement with that,” she wrote in The Guardian.

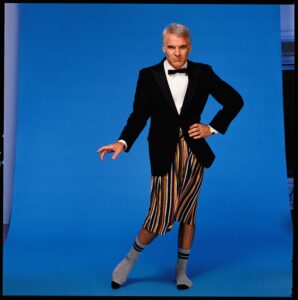

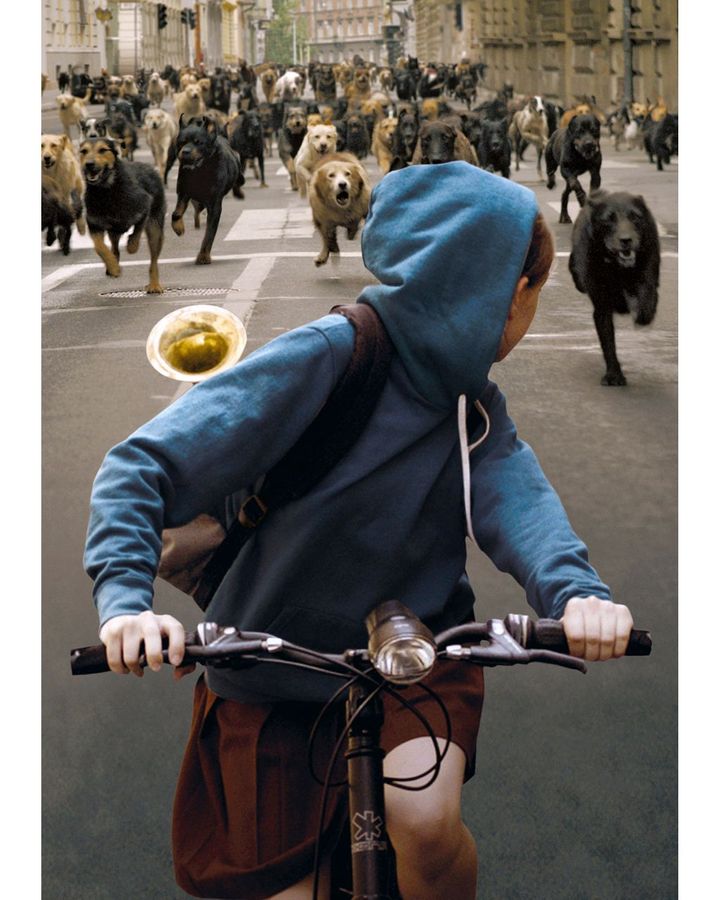

This new curiosity in a creaturely perspective is gradually finding its way into fiction filmmaking. White God (2014) subverts the typical animal-attack narrative of films like The Birds (1963) and Planet of the Apes (1968), portraying an animal uprising from a pound-bound dog’s point of view. Italian director Pietro Marcello’s Lost and Beautiful (2015) is a pseudo-documentary about the puppet figure Pulcinella, part-told by the buffalo who he leads to sanctuary. Michael Sarnoski’s Pig (2021), starring Nicolas Cage, was named after its truffle-hunting hog, in which the natural world seems to hang in the balance. This year, Martin McDonagh’s Oscar-nominated The Banshees of Inisherin features a standing-ovation-worthy performance from Jenny the Donkey and gives much more attention to the emotional gradations of its animal actors. In the past, animal actors have often been relegated to sentimental children’s films like Lassie Come Home (1943) or Babe (1995).

White God (2014) subverts the animal-attack narrative, portraying an animal uprising from a dog’s point-of-view (Credit: Alamy)

EO’s premise – of a donkey being passed between owners – is taken from Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), but in that film the animal is secondary to the human story, a narrative vehicle that shoulders the burden of the central characters’ actions. Said to be inspired by Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, Bresson’s parable centres on a man embodying Christian ideals, unable to survive the corruption of modern society. EO, is by contrast, enmeshed with contemporary environmental concerns, says Skolimowski. “This film was made out of a love for animals and love for nature,” he says. “Therefore, we were trying to express that love in every in every possible way, so not only the beauty of the landscapes, the gentleness of the behaviour of the animals but even by trying to add some humour into the story. We tried to tell it lightly, because the message was so important that we wanted to smuggle it in delicately.” That message, Skolimowski says, pertains to industrial farming methods: “Human nature is finally awake to the fact that meat consumption and especially industrial farming is something which ethically is very questionable. How can we allow ourselves to decide about the life and death of [other] living creatures?”

A changing perspective

In eco-critical studies, the term “anthropocentrism” – treating humans as the superior entity in the universe – has become key to discussions around environmental disaster. Many animal studies experts claim that countering this assumption is crucial to tackling the climate crisis, while the rise in vegetarianism and veganism over the past decade – spurred by greater public knowledge of unethical industrial farming methods – has also increased awareness of the non-human. “There has been a shift in the public in how we think about animals, mammals in particular,” Dr Anat Pick, a researcher who specialises in the intersection of animal and film studies, tells BBC Culture. “It may be the sentience of animals is no longer up for debate. It’s also partly to do with the climate crisis and people’s understanding that human beings are not alone in the world, that we are a part of something.”

“Anthropomorphism”, whereby a nonhuman animal or object is given human characteristics, is at the heart, John Berger suggested, of humans’ warped relationship with the animal world. Children’s books such as Beatrix Potter’s or films such as Homeward Bound (1993), which present a cast of talking animals, arguably turn them into mouthpieces for human issues and concerns. EO reaches for a much less anthropomorphic representation of its animal protagonist

EO borrows its premise from Robert Bresson’s 1966 film, Au Hasard Balthazar (Credit: Alamy)

Midway through the film, the donkey, having made his escape from a sanctuary and trekked through field and forest, wanders into a small Polish town. “The donkey was supposed to look at fish in a [shop window] but it looked, and it saw itself, its own reflection, and started to make a noise,” EO’s chief wrangler Agata Kordos tells BBC Culture. “That was a spontaneous reaction and was actually used in the film. Unlike a dog, which you can train to make noise on command, a donkey doesn’t do that. Sometimes you think that you’ve trained the donkey to make a noise on command, but it doesn’t work that way – he does whatever he likes.”

Moments like this, Pick suggests, are appearing more frequently in arthouse films and are what mainstream cinema should aim for: “Animals are narrative disruptors. Unless they’re trained, unless their movements are predictable, they introduce all these things that makes cinema feel wonderful – spontaneity, unpredictability, movement, dynamism and liveliness. If the director is committed to allowing that to happen, I think that makes for a great animal film.”

Animals taking centre stage

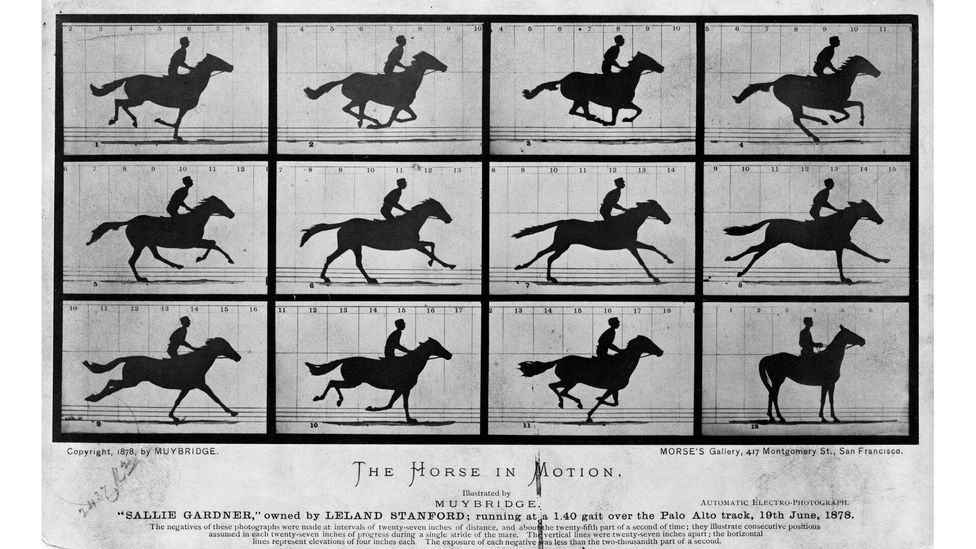

Animals have been on camera since cinema’s inception, with the first filmic technology producing Eadweard Muybridge’s Horse in Motion (1878). The earliest film to star an animal actor, Rescued by Rover (1905), saw a brave dog reunite a kidnapped baby with its parents, featuring collie Blair – soon to become a household name – as the hero. “These narratives of love, loyalty and affection from animals have travelled all the way through cinema,” Dr Claire Parkinson, author of Popular Media and Animals, tells BBC Culture. “There’s this romanticised reassurance of the human-animal bond.” In his 1993 book, Picturing the Beast, Steve Baker argued that animals have stood in as symbols for a nation in war films. Think War Horse (2011), which follows a four-legged hero on the frontline, or Dog (2022), starring Channing Tatum, a sentimental story about an army hound.

Animals have been at the centre of cinema ever since the first technology created Eadweard Muybridge’s Horse in Motion (1878) (Credit: Getty Images)

In cinema’s early years, animals were subjected to a fandom equal to that of human actors, from Rin Tin Tin – the German Shepherd who reportedly snagged the most votes for the first Academy Awards and saved Warner Bros from bankruptcy – to Rex the Wonder Horse, the madcap mare who acted in blockbusters across the 1920s and 30s. “Animal stars, particularly dogs, were treated in almost the same way in marketing and publicity as human stars were,” says Parkinson. “They got the same kind of coverage in the fan magazines. They would talk about what the dog was doing in the same way that they would talk about what humans were doing, as if the dogs were completely autonomous agents.”

Changes in regulations around animal welfare, led by the American Humane Association, have also steered today’s filmmakers away from using wild animals, such as lions and chimpanzees, as was once common. “In Hollywood, a lot of studios had their own zoos, and they would bring animals in from various different countries. They would have people who would go out, capture them, and bring them in,” explains Parkinson. This was evident in early skits such as Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus (1928) or, later, the infamous Bedtime for Bonzo (1951) – during its production, lead actor Ronald Reagan was nearly strangled when the monkey yanked his tie. “Certainly, in the first half of the 20th Century, people were fascinated by this idea of the African subcontinent, by the people and the animals,” says Parkinson. “So a lot of the films of the first half of the 20th Century would be promoted on the basis that they had these wild animals in them.

“If you went to a zoo, you would see animals doing tricks and performing,” Parkinson continues. “People were fascinated by the idea of animals behaving like humans. In the first half of the 20th Century, there was a lot of coverage of scientists who were bringing chimps up as if they were human.” The introduction of a film rating system in 1968, Parkinson says, is when audiences for animal films diverged, with two genres emerging: family-friendly films or the eco-horrors of the 70s and 80s. Dogs (1976), Long Weekend (1978) and Night of the Lepus (1972), for example, were about nature biting back, reflecting worries about human-inflicted damage.

These same concerns drive this latest wave of animal films, though the impetus seems to stem from empathy rather than fear. Pick is concerned that the compassion may end there: “We’re trying to reconcile our terrible relationship to other animals in our daily lives with our ability to empathise with them and recognise them as persons,” she says. “For me, there’s something very consensus-building and reassuring about these films. People go to the cinema, they watch animals suffer, they feel good about themselves for feeling bad.”

In cinema’s early years, animal stars like the German Shepherd Rin Tin Tin were celebrated as much as their human counterparts (Credit: Getty Images)

Parkinson believes that it will never truly be possible to convey an animal story on screen without forcing it in some way to fit the human mould. “Films are human-to-human communication, so for a narrative to work there has to be a human interpretation of animal behaviour and that’s on a spectrum: on one end, making an animal behave like a human would, to the other end which is to have human narration of animal behaviour,” she says. “It has to translate into a humanised story at some level, otherwise it would be incredibly difficult for us to make sense of.”

For Skolimowski, this was part of the appeal. Before embarking on the project of EO, the director and his wife and co-producer Ewa Piaskowska yearned for a storytelling method going beyond the classic linear structure – “which was a bit boring for us,” he says. “We wanted to do something different. In casting the animal character as the main character of the whole story, or even further of telling the story through the animal character, we were trying to offer a voice to the voiceless, of those who couldn’t speak for themselves.”

EO is released in the UK on 3 February.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.