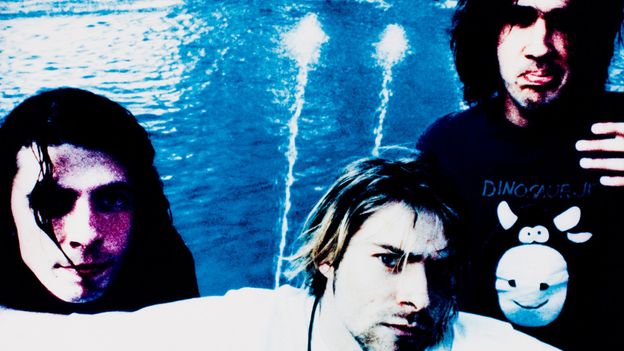

The album that shook the world

When Nirvana released Nevermind in September 1991 (on major label Geffen, following the band’s emergence on Seattle indie SubPop), the album’s explosive success followed a European tour and proved a shock to the mainstream system (Geffen president Ed Rosenblatt described it as “one of those ‘get out of the way and duck’ records”). Back on the Seattle DIY scene, the mood was less celebratory: “My memory of Nevermind is that it felt like a betrayal,” says Keshavarz. “People were protective because Nirvana were representative of a community and so many ideas. In retrospect, I have great sympathy for the band, because I think they legitimately made beautiful music that touched people’s hearts. In fact, I remember visiting Iran soon after Nevermind came out, and smuggling in tapes to play to friends and relatives; you’d see their faces, like: ‘What is this? It’s kinda cool… can I get a copy?’

“But within Seattle at the time, people were super-upset; it was that DIY ethic that believed you couldn’t achieve liberation through a major label. We knew rents and ticket prices would go up, and we were really protective of our spaces. Kurt would often turn up at the Old Fire House and just be quiet in a corner; he was a gentle soul, and everybody loved him – yet sometimes, he wouldn’t be welcome, depending on who was playing, because the anger levels were high. That must have been hurtful.”

Global reverberations

Nevermind has reportedly sold over 30 million copies worldwide, making it one of the biggest albums in music history. It also arguably forged a kind of globalised youth culture, fuelled by the increasing reach of MTV (which had its videos, including Smells Like Teen Spirit, on heavy rotation). Brazilian cultural studies academic Moyses Pinto, now a professor at Lutheran University in Porto Alegre, was struck by Nevermind’s initial release when he was 11. “I thought: ‘this is perfect’; it sounded like a bright synthesis of noise and pop music,” he says.

Neto points out that Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964-1985) inspired many rebellious musicians, including pysch-rockers Os Mutantes (one of Cobain’s favourite bands). The end of the dictatorship extended the range of rock, punk and post-punk sounds in Brazil, though Neto describes a “time lag” between international influences, before the age of Nevermind: “We had punks in Brazil, but almost a decade after their peak in the UK and US – and there was ’80s pop culture and mainstream arena bands,” says Neto. “But the impact of Nirvana and MTV made it synchronised; a new youth – including me – began to hear the same music, and wear the same styles; there was a cultural homogeneity probably never experienced before. Grunge culture became dominant very quickly; all that had been ‘cool’ suddenly became ugly and exaggerated, and Kurt was the symbol of transgression.”

Another Porto Alegre kid in ’91, Rogerio Maia Garcia, was intrigued by Nevermind’s “swimming baby” vinyl artwork (the album arguably heralded an era of visual iconography, as well as musical influence), right before the music captivated him: “We were all listening to rock and metal, but Nevermind sounded totally different – like ‘normal kids’ playing at home: raw, and really loud,” says Garcia. “It certainly opened our ears to the grunge scene; after Nevermind, bands like Soundgarden, Alice in Chains and Pearl Jam became well known in Brazil, and many kids started learning to play; in early ’90s Porto Alegre, live music had been losing out to dance music, but suddenly there were local band gigs every night.” He adds that established Brazilian bands such as Titas also incorporated the influence, working with Seattle producer Jack Endino for their own album Titanomaquia (1993).