The black composer erased from history

The Western classical music canon is notoriously white and male – so you might assume that a black Renaissance composer would be a figure of significant interest, much-performed and studied. In fact, the story of the first known published black composer – Vicente Lusitano – is only now being heard, alongside a revival of interest in his long-neglected choral music.

More like this:

– How the first pop star blazed a trail

– The singing contest that made history

– The music most embedded in our psyches

Lusitano was born around 1520, in Portugal. In a 17th-Century source, he is described as “pardo” – a commonly used term in Portugal at the time meaning mixed race. It is most likely that Lusitano had a black African mother and a white Portuguese father; Portugal had a significant population of people of African descent, due to its involvement in the slave trade.

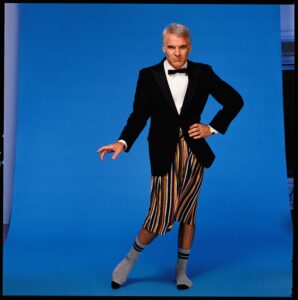

Among other things Lusitano was an expert music theorist – this is a page from his composition manual Introduttione Facilissima (Credit: IMSLP/Public Domain)

Comparatively little is known about Lusitano’s life – a fact which has certainly not helped his historical legacy – although what we do know is dotted with juicily intriguing details. “There’s a lot of things you could say about how cool he is as a person, and how exceptional he is as a figure,” promises composer, conductor and early music specialist Joseph McHardy, a recent Lusitano champion.

What we do know is that Lusitano became a Catholic priest, composer, and music theorist, and in 1551 left Portugal for Rome – a multicultural musical capital of Europe at the time – most likely following a rich patron, the Portuguese ambassador. Lusitano appears to have done very well for himself there, publishing a collection of motets: sacred, polyphonic choral compositions (where voices sing several layers of independent melodies simultaneously). Then, Lusitano became embroiled in a high-profile public debate around the rules of composition and the use and juxtapositions of different tuning systems or keys, with a rival composer, Nicola Vicentino. Consider it a Twitter spat of the Renaissance age – although with an official judging panel of eminent performers from the Sistine Chapel choir, no less.

In the final adjudication of their intellectual duel, Lusitano was unanimously judged the winner: an unlikely victory given that, as a foreign outsider, he was something of an underdog compared to the well-connected Vicentino. But, unwilling to let it go, Vicentino conducted a smear campaign against Lusitano, discrediting him and his ideas. In what would become a famous, printed 1555 treatise, Vicentino fabricated a misleading version of the debate so it looked like he had the better ideas, really – and it was this document that endured and this version that was later repeated in many textbooks.

Sometime after 1553, Lusitano converts to Protestantism – itself an unheard of development for an Iberian composer in the era. He also gets married, and moves to Germany; we know he receives payment for some music there in 1562, and applied for a job in Stuttgart.

But although his achievements in Rome suggests Lusitano won significant respect for his music in his lifetime, it wasn’t as widely copied or performed as some of his contemporaries, and seems not to have spread across Europe; this has led to some musicologists in Portugal appreciating him, but a failure to cut through among non-Portuguese speaking scholars since. Occasional flashes of academic interest have never transformed into sustained attention, an accessible and readily shareable modern score, or performances of the thing that really matters: his music.

The new Lusitano champions

Until, that is, very recently. During the pandemic, two Renaissance music lovers separately discovered Lusitano, and are staging concerts and bringing out records of his work, while a new piece reimagining a Lusitano composition is currently on tour across the UK.

In what he describes as the “darkest days” of the first lockdown, Rory McCleery – founder of British vocal ensemble The Marian Consort – read an article about Lusitano by an academic, Garrett Schumann from the University of Michigan, in VAN Magazine. Keen to find out more, McCleery was delighted to discover that Liber primus epigramatum, Lusitano’s 1551 collection of motets, had been digitised and put online.

“My proclivities have always been in finding Renaissance composers who have fallen between the cracks,” he says. “It’s always super exciting when you find a composer and start looking into their music and go, actually, this is very good. You want to evangelise about it – music is there to be shared.”

And share it, he did: The Marian Consort were including a Lusitano piece, Inviolata, integra et casta es, in concert programmes by December 2020 – probably the first time it had ever been performed live in the UK. Last summer, they weaved it into a Prom celebrating a much more famous Renaissance composer, Josquin des Prez. It was apt, given that Lusitano’s work is clearly in dialogue with Josquin – in Inviolata, Lusitano riffed on a hugely technically accomplished five-part composition by Josquin, impressively expanding it further, for eight voices.

A woodcut of composer Josquin des Prez, with whom Lusitano’s work was in dialogue; by contrast, there are no known pictures of Lusitano in existence (Credit: Alamy)

“Lusitano obviously liked to go, well this is all very clever – you’ve done one Rubik’s Cube, now I’m going to do four Rubik’s Cubes at the same time…” jokes McCleery. “But for me, what is so exciting is it’s a very beautiful piece of music, as well as a clever one.”

The Marian Consort release a full album of Lusitano’s music this autumn, and have also already teamed up with the organisation Classical Remix to tour a new installation, titled Lusitano Remixed, to both art galleries and music venues in the UK. Acclaimed opera singer and composer Roderick Williams was commissioned to write his own response to Lusitano’s Inviolata. It plays out of eight speakers arranged in circle, one speaker for each of singer, which the listener can move around; experiencing it at the Samuel Worth Chapel in Sheffield, I found it offered an immersive, spatialised experience, soaking you in a soaring surround-sound while also allowing you to get up-close and intimate with individual voices.

“I, like most people, had never heard of Lusitano,” admits Williams when discussing his piece, which directly quotes Josquin, then Lusitano, before “exploding” into his own contemporary interpretation. “The whole idea of The Marian Consort doing their research about him is that he has been forgotten by history – through malice, through ignorance. We are beginning to wake up, all of us, to the idea that there were mixed-race composers in the past.”

McCleery was not the only one who had a fortuitous chance encounter with Lusitano in 2020. During Black Lives Matter protests, McHardy saw a picture on Twitter of someone holding a placard depicting black composers through history, reading ‘teach these composers’ – including Lusitano, who he’d never heard of. McHardy googled him, also found Schumann’s article, and got in touch.

Since then, the pair have been working on the fairly mammoth task of turning Lusitano’s part books – all the separate, individual vocal parts for his motets – into one unified score with modern notation, so they can be more easily understood and performed. A scholarly edition is planned, alongside a recording (likely out early next year), while there are three concerts of his work this week by black and ethnically-diverse vocal ensemble Chineke! Voices.

You might expect some rivalry, from two early music specialists, both uncovering this forgotten figure simultaneously. But both, really, just seem delighted more people might hear Lusitano’s music.

“Lusitano’s moment has come – he’s in the zeitgeist, which is fantastic because his music really does deserve to be better known,” says McCleery. And both men are also staunch in insisting that this revival of interest is not just about the eye-catching fact that Lusitano was a composer of African descent – it’s that his music stands up.

The beauty of his music

“It’s really difficult choosing the pieces [to include], because they’re all really good!” says McHardy, promising that Chineke!’s record, as with the concerts, will feature 90 minutes of “top level Renaissance polyphony”. He also wanted to include a range of Lusitano’s work: some of his “really complex eight-part masterworks” but also pieces that are significant to his story, such as his adventurously weird, chromatic motet Regina coeli, which is thought to have kicked off that feud with Vicentino.

What exactly appeals, then, about Lusitano’s music? “Fundamentally, it’s just really beautiful,” says McCleery. “There are very long arching phrases that seem to spin out into eternity. But also this interesting use of chromaticism: slightly spicy moments – the musical equivalent of feeling metal on metal.”

If you have ever encountered Lusitano, it’s likely to be his most chromatic piece, Heu me domine, which has attracted some interest since the 1980s precisely for its experimental dissonance. In fact, this etude comes from within a theoretical treatise on counterpoint and improvisation that Lusitano wrote – it was more intended to illustrate a point, than as a composition to be performed.

Composer and conductor Joseph McHardy has been one of the music experts helping to champion Lusitano (Credit: BBC)

“It’s a very cool piece. But it isn’t super representative [of Lusitano’s music],” says Schumann. Instead, Schumann also reaches for the word “beautiful” when trying to summarise Lusitano’s richly layered polyphony: “It’s just really, really gorgeous.” “‘Opulent’ is a good word for it,” chimes in McHardy.

The music is worth revisiting, then. But for contemporary audiences, Lusitano’s identity and biography – patchy as it is – of course proves a source of enormous fascination, too.

What do we know about how his race may have affected his career prospects – in his own lifetime, and since? Much is speculation – but it is likely that Lusitano faced some prejudice, and there are specific ways his identity certainly disadvantaged him. In Portugal, he would have been barred from getting a job in one of the big, major churches because of his race. “The papal bill that allowed African descended men to be ordained Priests specifically forbad them from holding benefices in the Portuguese church,” explains McHardy.

One piece that McHardy is recording, Quid Montes, Musae?, is a rare secular composition, based on a poem asking the muses to relocate to Italy with the Portuguese ambassador. McHardy speculates that Lusitano may have written the words himself – another cool and unusual thing for a composer at that time. And one that may provide a glimpse into how Lusitano felt about being pardo in Portugal…

“It talks about Portugal in some derogatory language: ravening beasts and inhospitable rocks, everything is scary and everything promises death…” explains McHardy. “On the surface, you go ‘OK, this is a Renaissance person writing neo-classical stuff’. But if you put it in context – that this comes from the pen, and may well have been sung in the mouth, of someone who was discriminated against [via] Portuguese legal and societal racism – I think it has some more layers to it. It feels like his personal voice.”

In terms of how Lusitano’s race may have affected his reception since… well, that’s a tale of two parts. Lusitano is described as pardo in an unpublished manuscript about Portuguese musicians by João Franco Barreto, written in the mid-1600s – but in 1752, Diogo Barbosa Machado, the author of the first printed encyclopaedia of Portuguese composers, chooses not to repeat this detail. So anyone reading about Lusitano after that would likely not have even know he had African heritage. It was only in 1977, when Portuguese musicologist Maria Augusta Alves Barbosa returned to the original unpublished manuscript, that this fact became widely known.

Was the decision not to include Lusitano’s racial identity in the 18th Century itself racist? Possibly. Schumann wonders whether it may have been an act of erasure by Machado, seeking to promote a certain view of their nation through music. “At the time Portugal was being extremely legalistic about racial categories because they were trying to exclude people of African descent from property rights, so it may have been a political motivation. But it is [also] part of a broader scheme of making it seem like the only people who participated in this tradition were white men.”

Vocal ensemble The Marian Consort have been performing Lusitano’s music, after their founder came across a feature about him during lockdown (Credit: Lusitano Remixed)

Which leads us on to a point Schumann finds even more depressing: even today, he continues to meet resistance to the idea that Lusitano was black mixed-race.

“People have been talking with confidence that he is black for at least 50 years – and yet it is still considered controversial! Music scholars refuse to believe it,” he says. “And the reason people find it hard to swallow is we were told there were no black composers, when there were. There is evidence that there were [unpublished] black composers in Europe in the 14th-Century. Lusitano is an important landmark – but he’s not the start of that story.”

Not that it’s all gloom. There seems to be an increasing appetite among the public for uncovering a more diverse musical history, and renewed efforts by people programming concerts to showcase a greater variety of work. And at least now we can put paid to the idea that there simply weren’t any non-white composers writing music in the Renaissance, McHardy points out.

“We found the music for you, here it is: it’s pretty, it sounds nice, you can read it really well… That can move things on a bit,” he acknowledges. “Then people have to make a choice about whether they want to perform it or not. Which is a different situation to going ‘I couldn’t find any’.”

“I think the more Lusitano’s music gets heard, the more people will be interested in performing it,” concludes Schumann. “It’s really good music.”

‘Lusitano Remixed’ is at St George’s Bristol until 27 June 2022, classicalremix.org. An EP of the recording is out now, and The Marian Consort’s album, ‘Vicente Lusitano: Motets’ will be released 23 September.

Chineke! Voices perform ‘The Music of Vicente Lusitano’ at St George’s, Bristol on 16 June; Worcester College, Oxford on 17 June, and St Martin’s in the Fields, London on 18 June, chineke.org/events

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.