The book that ‘could corrupt a nation’

When a book has been banned on grounds of obscenity, a reader may be forgiven for coming to it with certain expectations. In the case of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, those expectations are decidedly misleading. For all the clasping of hands and flushing of cheeks that fill its nearly 500 pages, this is no Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Both were published in 1928 and subsequently banned, but whereas DH Lawrence described his protagonists’ trysts in vocabulary that would still necessitate asterisks here, Hall stops at the bedchamber door. Aside from a kiss that is “full on the lips, as a lover”, the coyly phrased “that night they were not divided” is as racy as The Well of Loneliness gets.

More like this:

– A Soviet novel ‘too dangerous to read’

– The shocking history of books that were censored

– The books that really change the world?

The controversy of course stemmed not from what was being done so much as who was doing it with whom. If Lady Chatterley caused a scandal by showing lust to be no respecter of class boundaries, Hall’s novel was still more shocking because its protagonist, despite being named Stephen Gordon, is a woman, and her supposedly masculine proclivities extend far beyond her name. She weightlifts and refuses to ride side saddle; she gets her clothes made by a tailor rather than a dressmaker and longs to cut her hair short; and from a young age she’s prone to unusually intense feelings for other women.

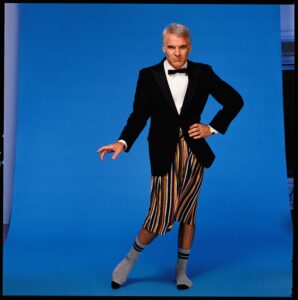

Hall dressed in men’s fashion, such as trousers, monocles and hats (Credit: Getty Images)

In early adulthood, those girlish crushes blossom into a torrid affair with a bored American housewife, Angela Crossby. After Stephen’s mother, Lady Anna, finds out and banishes her from the family home, Stephen becomes a writer and travels to Paris, where she’s taken under the wing of a lesbian salonnière. Later, she serves in the ambulance corps during World War One and falls for fellow servicewoman Mary Llewellyn – she from whom Stephen will be “not divided”.

The novel chronicles her nascent understanding of differences she’s sensed in herself for as long as she can remember – differences dubbed “queer” behind her back. However, what truly sealed its fate when it landed in the dock at Bow Street Magistrates Court mere months after publication is the case it dares to make for recognition and tolerance of Stephen’s sexuality. Hear her plea at the novel’s fevered end: “Rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!” Not only is this a novel that strives to humanise the experience of outcast lesbians, it also argues for equality.

In 2019, newly revealed papers from Hall’s archive at the University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Center showed that thousands of readers had written to her to protest the novel’s ban. “It has made me want to live and to go on,” wrote one. Unlike male homosexuality, lesbianism wasn’t in fact illegal in the UK in 1928, though that position should not be mistaken for tolerance. In fact, Stephen’s prayer was destined to grow only more radical-seeming for some decades to come, and for generations of women – and men – on their own difficult passages to sexual self-discovery, The Well of Loneliness became a beacon.

Speaking in a recording for the Hall-Carpenter Oral History Archive, a reader named Rene Sawyer, who was a teenager when the book was finally republished in 1949, explained its importance: “To me it was my bible. To me: it had every aspect of tenderness, of love, of heartache, of anguish, of problems – physical and mental problems – it had everything in that book. Which for me was a lifeline at that time.”

If the book’s historical and cultural significance is unquestionable, its text inevitably feels dated almost a century on. There’s Hall’s language, for starters. The first edition carried an “appreciation” by her friend Havelock Ellis, the sexologist whose theory of “sexual inversion” she supported, and his word “invert” – until then restricted to scientific literature – appears throughout Stephen’s story.

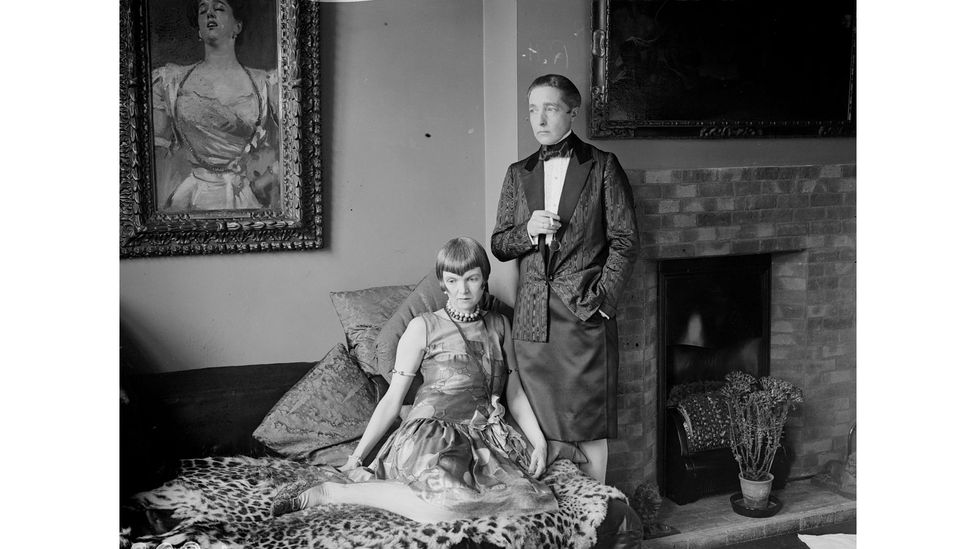

Hall described herself as a “congenital invert” – a phrase taken from the writings of Havelock Ellis and turn-of-the-century sexologists (Credit: Getty Images)

Also jarring is the apologetic way in which Stephen’s sexuality is framed, and the sheer pessimism surrounding Hall’s depiction of gay life. As a devout Catholic, it was no coincidence that she named her protagonist after the first Christian martyr, and ultimately, she has Stephen embrace drastic self-sacrifice in her love life.

The novel has been slated, too, for its limited depiction of lesbianism as being so determinedly butch, it might almost seem a form of heterosexuality. And it’s been called bi-phobic for the way it depicts Mary Llewellyn, who has relationships with men as well as with Stephen, and misogynistic for the way in which it denies her any say in her own future. Its descriptions of gay men, meanwhile, read like crass caricature. There’s also its racism and classism, which can be shocking to encounter in a text that’s gone down in literary history as being so radically progressive.

Pulp fiction

Nor is there any getting away from the fact that this is simply not great literature. The book is long-winded and full of stilted dialogue. Change a few pronouns and in some ways, it resembles the pulp romances of its era. Writing in The Times in 2008, Jeanette Winterson didn’t mince her words, declaring that “The Well of Loneliness is one of the worst books yet written”.

As with other banned books, this is a novel whose status is intrinsically linked to its having been censored. As Professor Laura Doan, who co-edited Palatable Poison: Critical Perspectives on The Well of Loneliness, tells BBC Culture, “In a way, the function of The Well of Loneliness is to convince you that lesbianism matters – lesbianism matters so much that the government can ban us and silence us, and that works very well to put you on the cultural map.”

In recent years, however, discussion of the novel has been turbocharged by fresh debate. This time, the controversy stems less from its content than from the extent to which we choose to view it through the lens of 21st-Century gender identity politics. A woman who dresses like a man, goes by a man’s name, and is described as being “midway between the sexes”: could it be that one of the world’s most famous lesbian novels has all along been a trans novel? Whatever you conclude, there’s no denying that this book continues to challenge received beliefs and to polarise readers, sometimes in ways that not even its author could have anticipated.

Hall was with her partner Una Troubridge for many years; the two collected Dachshunds (Credit: Getty Images)

Born in Bournemouth on 12 August 1880, Marguerite Radclyffe Hall did not have an easy childhood. Her wealthy, philandering father left the family when she was a baby; her mother, an American who’d already been divorced once before and was prone to violent outbursts, rejected her daughter’s boyish ways. She later remarried an Italian singing master, and there are hints that he abused Hall.

At the age of 21, Hall came into a substantial sum of money from her father, giving her the security and freedom to leave home. She’s said to have written poems and songs from the age of three, and in her twenties, published some books of poetry. She was encouraged by her first long-term lover, amateur singer Mabel Batten, to try her hand at short stories, and was then persuaded by a publisher to write a novel. Her first, The Unlit Lamp, was published in 1924. Two years later, her fourth, Adam’s Breed, won a clutch of prizes and sold 27,000 copies in its first three weeks.

Its success emboldened her to risk writing The Well of Loneliness. By then, Batten had died and Hall was in a relationship with Batten’s cousin, Una Troubridge. The pair were as “out” as it was possible to be in 1920s England – a life made easier, undoubtedly, by the privileges of wealth and class, but there were furtive elements to their existence all the same. Troubridge supported Hall’s decision to publish The Well, and in the spring of 1928, Hall wrote to her publisher, Jonathan Cape, to warn him: “I have put my pen at the service of some of the most persecuted and misunderstood people in the world”. She added: “So far as I know nothing of the kind has ever been attempted before in fiction”.

The Well of Loneliness was eventually published in 1949 (Credit: Alamy)

Is it autobiographical? Despite very different childhoods, there are certainly physical similarities to be spotted between Stephen and her creator: both are tall and “handsome in a flat, broad-shouldered and slim-flanked fashion”. Stephen is her protagonist’s given name – having been convinced she’d be born a boy, her father decides “Stephen” will work equally well for a girl – but from her mid-twenties, Hall was known to her intimates as “John”, a nickname given her by Batten. Like Stephen, she wore men’s clothes.

The novel garnered positive reviews in The Times Literary Supplement and Time and Tide but no critic was as convinced of its potency as James Douglas, editor of the Sunday Express. Certain that it would contaminate and corrupt English fiction (his words), he wrote an article damning it as “unutterable putrefaction”, notoriously declaring: “I would rather give a healthy boy or girl a phial of prussic acid than this novel”. The book should be withdrawn, he thundered, or else the Home Secretary, Sir William Joynson-Hicks, must act to suppress it.

On trial

It was sensationalist journalism but Joynson-Hicks was a man who had even found cause to object to a revised version of The Book of Common Prayer. He threatened Cape with criminal proceedings if the book wasn’t withdrawn. Cape complied, though not without first licensing the rights to Pegasus Press, an English language publisher in France. Inevitably, copies found their way back into Britain and a trial ensued – with the Home Secretary claiming the novel “supports a depraved practice and that its tendency is to corrupt, and that it is gravely detrimental to the public interest”.

Among the writers who rallied to the novel’s defence were EM Forster, Vita Sackville-West and George Bernard Shaw, though not all were convinced of its artistic merits. Virginia Woolf, for instance, thought it a “pale tepid vapid book” and dreaded having to take the stand for it. She needn’t have worried: the magistrate, Sir Chartres Biron, ruled that authors could not testify as literary merit was irrelevant. On 16 November 1928, he found the novel to be obscene on the basis that it had the ability to corrupt, ordering its immediate removal from circulation. An appeal the following month similarly failed, with judge Sir Robert Wallace labelling The Well as “more subtle, demoralising, corrosive, corruptive, than anything that was ever written”.

The judgements did nothing to dent support for Hall, who appeared in the courtroom wearing a leather driving coat and Spanish riding hat. She was described by the Daily Herald as “well-chiselled”, and at the conclusion of the obscenity trial, according to the Daily Express, two women approached her from the crowd, took her hand and kissed it.

Hall’s legacy endured – her photo appeared in a 1982 Pride Parade in New York City (Credit: Getty Images)

Suppression would be the making of both the novel and its author’s reputation and yet in the decades since, this supposed Sapphic survival guide has continued to attract plenty of criticism from diverse quarters. In the 1970s, for instance, it became the focus of a backlash from Second Wave feminist critics for its patriarchal worldview. And by 2017, Winterson still hadn’t warmed to it – although she chose it as the book that helped her come out, and argued that “A book can be bad and still have a place in history”. Writing this time in The Guardian, she asserted: “The Well reads like a misery memoir long before they were invented. It’s the fictional story of Stephen Gordon and her struggles with the fact that she thinks like, acts like, loves like and wants to be a man. Radclyffe Hall had no idea that sexuality is a spectrum, not a binary”.

Hall’s beliefs definitely complicate the book’s legacy. Contrary to what might be expected of a pioneering lesbian author, her politics were reactionary at best. As an expat living in Italy in the lead-up to World War Two, she not only supported Mussolini’s Fascist government, she also supported its censorship – of books. And if Victorian womanhood wasn’t for her, she fully supported it for others, believing that a woman’s place was in the home.

For Professor Doan, much has changed in terms of how the novel is discussed. “When you read it today you do feel that there’s a lot in it that makes you feel pretty embarrassed by it,” she says, noting that its racism, for instance, was scarcely talked about even a couple of decades ago.

These days, she prefers to direct anyone interested in learning more about Hall to Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself, a short story written in 1926 in preparation for The Well. This story holds the key to the novel’s real meaning, Doan believes. “To me, that story is about a human who is trapped in the wrong body, has been designated as a female and doesn’t feel like a female and has a fantasy of becoming a male. There’s no desire or love or romance in that story, and it made me realise that The Well of Loneliness isn’t about love between women either.”

Doan says she was never really convinced that The Well was a lesbian novel. As she explains, “It would be a better text to think of in the context of trans history. The publishers would be missing a commercial opportunity right now if they didn’t try to push its cultural meaning to the trans community. If they want to identify a text that is at the start of the awareness in culture of the possibility of a trans existence, it’s got to be The Well of Loneliness.”

So should we be using a different set of pronouns for Hall and Stephen? Some scholars, including Jana Funke, associate professor of English and Sexuality Studies at the University of Exeter and editor of The World and Other Unpublished Works by Radclyffe Hall, now use gender-neutral pronouns for both author and protagonist.

Maureen Duffy takes a different view, seeing Stephen’s gender nonconformity as a function of Hall’s discomfort with her own lesbianism. Writing in her introduction to the most recent Penguin Modern Classics edition, Duffy uses a pivotal scene from the novel to make her point: defending herself to her mother, Stephen justifies her sexual intimacy with Angela Crossby by explaining that she’s “never felt like a woman”. It’s an argument Hall insists upon, Duffy suggests, “in order to justify her own very active homosexuality, which she embraced in spite of her espousal of Roman Catholicism”.

It’s worth noting that even readers for whom Hall clearly had a desire, however latent, to transition, The Well of Loneliness is by no means a straightforward text. Oliver Radclyffe, the trans author of a forthcoming monograph, Adult Human Male, changed his surname in homage to Hall. He’s written on the website Electric Literature about how his feelings for the book changed as he undertook his own journey from Englishwoman raising four children in the Connecticut suburbs, to femme lesbian, to trans man. As he puts it, “it looked like Radclyffe Hall had not only been a gay rights activist but also a patriarchal misogynist with consensually-ambiguous domination issues”.

Ultimately, it isn’t possible to know whether or not Hall would have identified as transgender – a term not coined until much later – and labelling this long-dead queer person as such is innately problematic. What is certain is that more than 90 years after it was banned, this decidedly flawed piece of literature continues to make readers think anew. As Doan says, “We’re confronting its complexity, and that can only be a good thing.”

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.