The masterpiece that changed history

In 1930, Henri Matisse, one of the giants of 20th-Century art, found himself in a discouraging creative slump. At the age of 60, the painter had been living in Nice, France, for 13 years, after spending years in Paris as an enfant terrible of the city’s avant garde art world. Isolated from the buzz of the Paris painting scene, Matisse focused on depicting alluring female models in interior studio setups, using vivid patterns and sparkling colours lit by the Mediterranean light. As he fell into a stylistic repetition, some critics, along with Matisse himself, wondered if the once-radical artist had lost his edge. “I have sat down several times to do some [painting],” he wrote to his daughter, Marguerite, in 1929. “But in front of the canvas, I am at a loss for ideas.”

More like this:

– The portrait that questions history

– The women who redefined colour

– Why we’re fascinated by art fakes

Now, a gorgeous, provocative exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art shows how Matisse broke free of his painting stagnation in the late 1920s, and transformed into a revived decorative artist during the 1930s. Matisse in the 1930s is the first major exhibition to look at the painter’s evolution during this phase of his long, creative life. Presenting 143 works, it offers a rare opportunity to explore Matisse’s process as he worked through a productive decline – especially relevant today, after many artists experienced isolation and creative paralysis during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Curated by Matthew Affron of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Cécile Debray of Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris and Claudine Grammont of Musée Matisse Nice, the exhibition travels to France in March and along the way asks, how does an artist forge ahead after a creative slump? What does it take to maintain a creative drive over a lifetime? A recent Americans for the Arts study found that 64% of 20,000 artists surveyed said they experienced a decrease in their creative productivity during the pandemic. More than half said their decline was due to stress, anxiety and depression about the state of the world. Matisse’s creative painting output fell during the start of a world-wide economic depression, the rise of fascism in Europe and, more immediately, a personal sense that his approach to easel painting was in crisis.

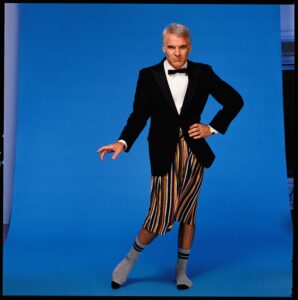

The exhibition shows how Matisse – pictured in 1951 – broke free of creative stagnation and transformed as an artist in the 1930s (Credit: Alamy)

Organised chronologically, Matisse in the 1930s begins with a look at the Nice period, exemplified by his voluptuous Odalisque with Grey Trousers (1927). A seductive model in harem pants lays on a green bedroll, surrounded by brilliant red and yellow wall patterns. The touchstone painting is quite stunning, as are others in this section. But after leaving the room filled with pleasing nude after nude, we see a fixation setting in. It seems that outside of the noisy Paris art world, Matisse had perhaps become complacent late in his career, turning inwards, painting interior studio worlds in traditional perspective, illuminated by the striking Mediterranean sun.

“Fixation can play a part in creative blocks,” says Yale University professor and creativity expert, Jonathan S Feinstein, author of the forthcoming book, Creativity in Large-Scale Contexts. For a creative person, Feinstein tells BBC Culture, fixation means that an artist has been using a certain mindset, set of tools, themes or styles and then becomes fixated on this way of seeing the world and creating.” It can be difficult psychologically to break the fixation because this way of thinking has been reinforced in your mind over years of thinking about, in this case for Matisse, his approach to painting,” adds Feinstein.

The 1927 Odalisque with Grey Trousers, though beautiful, showed how the painter had become creatively paralysed (Credit: Musée de l’Orangerie / H Matisse / ARS)

And the critics at the time noticed. By 1927, they viewed Matisse as “the ageing painter of the odalisques,” according to the exhibition’s catalogue, “the man André Breton described as ‘a discouraging and discouraged old lion’.” Furthermore, his easel painting output slackened and between 1928 and 1929, he produced only a few oil works on canvas, though he was still drawing and working in sculpture. It looked as though Matisse had internalised what the critics were saying: his best years as a renegade painter were behind him.

Creativity maven Julia Cameron, whose 1992 book, The Artist’s Way, has helped thousands of artists around the world harness and maintain their creativity after a block, notes that even artists as renowned as Matisse can internalise criticism and fall into a slump. “This is true even if we’ve had wonderful reviews in the past,” she tells BBC Culture.

One of the world’s most renowned contemporary artists, Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei, who was recently in London’s Hyde Park giving away art to support global refugees, says he went through a similar creative block when he moved from the US back to China in 1993, albeit without the criticism that Matisse faced. After 10 years of producing notable photography while studying art in New York, upon his move in 1993,”I became very confused because I could not find an appropriate relationship with the Chinese culture, although I was both familiar and unfamiliar with it,” he tells BBC Culture. “I actually wanted to shun it but couldn’t process how.”

The renowned contemporary artist, Ai Weiwei went through a similar creative block when he moved from the US back to China in 1993 (Credit: Alamy)

Ai needed to remain in China to work through his block. But at the end of the 1920s, when Matisse realised he needed to revitalise his creativity, he began to travel, first to Tahiti and then the US.

The US abstract installation artist Judy Pfaff, who was heavily influenced by Matisse when she started painting in the 1970s, says travel helps many artists like herself to reinvigorate creativity when feeling stuck. “Travel has kept me moving forward,” the MacArthur Foundation Award-winner tells BBC Culture. “Whenever I’m in a new place, be it India or China, that gets incorporated into my work.”

Finding a new style

After touring around the US by train, in the autumn of 1930 Matisse went to Philadelphia to meet collector Alfred Barnes at his museum in one of the city’s suburbs. There, Barnes lightly confronted the ageing painter, pointing out that his Nice paintings were sensuous and appealing, but a bit lightweight compared to earlier works, according to Cynthia Carolan, a docent at the Barnes Museum, now located in the heart of Philadelphia. Barnes offered Matisse a commission: to create a painting that would fit under massive arched windows in his new museum. Matisse accepted the commission and, in turn, faced an enormous challenge. Firstly, he had never created anything this large, Carolan notes: the area of the museum for the mural was about 45ft (13.7m) wide and three separate canvases were needed to fit between two windows. Secondly, he had never had to make a painting fit architecturally accurate proportions, which is much more complicated than painting on a portable canvas.

To start the project, Matisse looked back to an earlier painting he made in 1910, now called The Dance I, to distinguish from the Barnes piece, which was named The Dance II. The first dance painting represented one of Matisse’s early turns towards a more simplistic approach to painting, using the basic elements of line, colour and form. Reacting to the introduction of photography, which could render details much more realistically than a painter could, The Dance I was an attempt to push painting to convey emotions through basic visuals rather than compete with a photograph’s ability to depict exact reality.

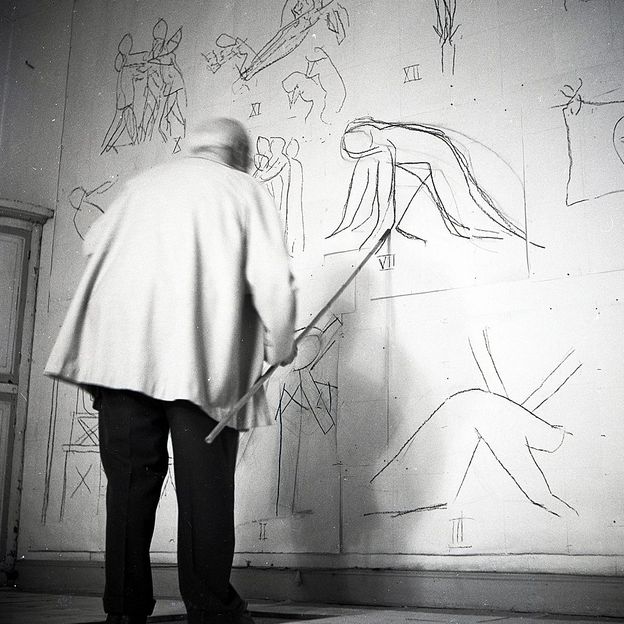

Photographs, plans and preliminary sketches in the exhibition detail how Matisse worked through these challenges. To create the mural, he rented a garage large enough to work on the outsized canvases. Wanting movement in the piece, he looked back to his earlier work to move forward and decided to recreate a group of dancers from his seminal The Joy of Life (1906) as the basis for what would become The Dance II. He first made a small drawing and blew it up to fit the canvas, but the proportions were off, according to Carolan. He needed to figure out a way to sketch his drawing on a large canvas where it would be difficult to wipe it out or paint over it to make changes.

Matisse then realised his normal tools of oil paints and brushes couldn’t make his vision come to life, so he found new ones. He began by using a long bamboo pole attached to a pencil as an elongated drawing tool to sketch the dancers’ shapes. Then, over the course of months, he tried cutting large pieces of pre-coloured paper and pinned them up, which helped to set the piece’s proportions. For the first time, Matisse used scissors as an art tool, ushering in the age of his renowned cut-outs. He also began using a camera to document his process so he could compare changes from day to day.

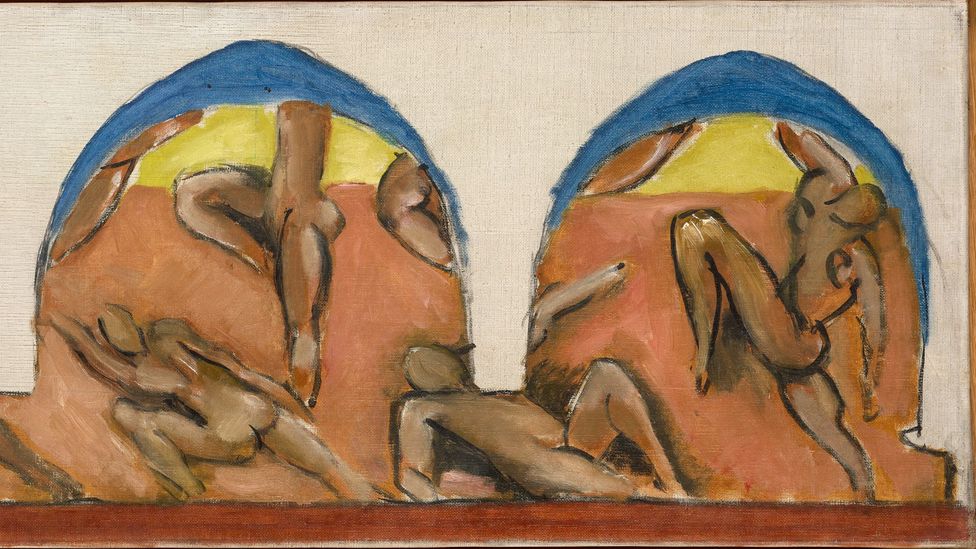

A study for the Dance II, at the Barnes Foundation, which required Matisse to overcome several challenges of scale, and proportion (Credit: Musée Matisse, Nice / H Matisse / ARS)

Matisse spent three years on The Dance II, and in the process marked a return to a modernist style, ultimately creating a dynamic composition depicting bodies that seem to jump across abstracted space of pink and blue fields. “He was able to transform his creative work through a certain kind of environment and tool,” says Ai Weiwei. Most artists usually work in a reverse direction, he points out, and use familiar techniques on different subject matters. “Matisse used diverse methods in subversive manners,” Ai adds, and in the process of trying to master these methods, an artistic language emerged that allowed the French master to enter a relatively free state of creativity.

The last sections of the exhibition are revelatory, showcasing Matisse’s new style, which distilled paintings down to pure line and bold colour. For example, in 1937’s Yellow Odalisque, Matisse’s mind was no longer confined to ideas of perspective and depicting an interior reality. Instead, the painting features a flattened composition with a black line-drawing within bright blocks of yellows, greys and reds. The bright, decorative Woman in Blue (1937) also reflects Matisse’s new artistic language, focusing on a balance of serenity between bare lines and pattern movement. With a new studio assistant and model, Lydia Delectorskaya, Matisse was now invigorated and less interested in perspective than in how space interacted between objects and patterns. He returned to still-life and model paintings aiming to evoke pure emotions, no longer beleaguered by negative reviews or fixations.

The colourful Woman in Blue (1937) reflects Matisse’s new artistic language (Credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art / H Matisse / ARS)

His shift from canvas painting to using pre-painted paper cutouts in The Dance II profoundly influenced generations of contemporary artists from Romare Bearden to Robert Motherwell and Pfaff. Ultimately, the exhibition proves Matisse lived up to his own famous words: “An artist should never be a prisoner of himself, prisoner of style, prisoner of reputation or prisoner of success.”

When Ai Weiwei was detained by Chinese authorities for nearly three months in 2011, he had no way to create art, he says. Instead, he challenged his mind to understand the people who imprisoned him and the system they worked under, he tells BBC Culture. “Imprisonment for me is a special training for a language, a new way to speak instead of what is commonly understood as a deprivation of freedom.”

Ai worked through the challenge to come out with a new strength and perception of how to be creative, going on to make some of his most engaging, culturally challenging work from 2012 onwards. “The kind of freedom I obtained there was something I could not have [developed] if I hadn’t been imprisoned in the first place,” he says.

Like Ai Weiwei, by working through creating The Dance II, Matisse broke through the quarantine of his own mind to come out the other end with a revolutionary new style of creative expression. His new focus, strictly on simple lines and bold colours, represents a complete departure from realism, speaking to his and his viewers’ emotions rather than just intellect. The invention of cut outs resulted from a profound creative process that went on to influence artists and enchant audiences into the next century.

Matisse in the 1930s is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until 29 January, at the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris from 27 February to 29 May and at the Musée Matisse, Nice from 23 June until 24 September.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.