The most beloved French writer ever

“How long Colette has lived, even after her death!” wrote the journalist Janet Flanner in 1967. More than half a century later, Colette lives on still, and this week sees the 150th anniversary of her birth. To mark the occasion, NYRB Classics has published a new translation of her twin masterpieces, Chéri (1920) and The End of Chéri (1926), translated by Paul Eprile – and this seems like a good opportunity to explore the life and work of this uniquely beloved of French writers.

More like this:

– America’s greatest living writer?

– Why the most difficult novel is so rewarding

– The shocking memoir of the ‘lost generation’

Colette’s fame extends to being probably the only female writer known by her mononym – she is always and only Colette, though in fact this most feminine of names was her surname: she was born Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette on 28 January 1873 in the French village of Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye.

Her work – mostly at novella length, short and sharp – survives because her chief subject is one that never goes out of fashion. “Love, the bread and butter of my pen,” she wrote, though she put it more bluntly in her book The Pure and the Impure (1932): “The flesh, always the flesh, the mysteries and betrayals and frustrations and surprises of the flesh.” André Gide, that great connection point for 20th-Century French literature, agreed, praising Chéri for its “intelligence, mastery and understanding of the least-admitted secrets of the flesh”.

The story of Colette and her work is one of the most astonishing in modern literature. She was a pioneer of the French school of autofiction (autobiographical fiction), writing about women’s lives in ways that broke new ground. Her books were simultaneously popular and acclaimed – read by critics and the public alike – not to mention scandalous. And she made of her life a project just as fascinating as her books. But to understand her – her fertile productivity, her showiness, her expertise in the mysteries of the human heart, and her appetite for including herself in her books, disguised either lightly or not at all – we must first understand that she almost didn’t become famous in the first place.

A runaway success

Her first four books were the chronicles of fictional French schoolgirl Claudine – Claudine at School (1900), Claudine in Paris (1901), Claudine Married (1902) and Claudine and Annie (1903) – which she wrote at the behest of her first husband Henry Gauthier-Villars, a journalist and editor known by the less elegant pen-name of Willy. Once she wrote them – at times locked in a room to spur her to completion – and they were garnished with a few editorial suggestions by Willy (“Some girlish high jinks… you see what I mean?”), Willy had them published under his own name and kept the copyright and royalties.

Colette’s first husband “Willy” published her first books under his name, keeping the copyrights and royalties (Credit: Alamy)

In reports about Colette’s life, the usual word to describe Willy is “deplorable”, and so he was, but he did give Colette a taste for Parisian cultural life – she met Marcel Proust, Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy and more – and did his bit to boost the sales of “his” books, which were slow until he arranged for three of his friends to write favourable reviews. Soon Claudine at School took off, and by the time the series was complete, the books were so popular they spawned stage productions and a range of merchandise, including Claudine cigarettes.

The books are apprentice work by definition – Colette wrote them in her twenties, under duress – but for a writer who started reading Balzac at the age of seven, that is no criticism. Claudine became what Colette’s biographer Judith Thurman called “the century’s first teenager”, with her sponge-like absorption of adult behaviour, and in the books we see the development of Colette’s mastery of sensuous description, as well as her first ransackings of her own life for material (which can make reading the wedding night scene in Claudine Married a somewhat voyeuristic experience). It was in these books, too, that we saw Colette’s first handling of love in fiction – although Claudine in Paris is probably the last book where Colette would write about love uncritically, romantically, without the power dynamics and ambiguity that made her later work so piquant. (“Men are terrible,” she once wrote, adding, “Women, too.”)

Colette and Willy separated in 1906, and the following year she published (under the name Colette Willy) Retreat from Love, which continued the story of Claudine and Annie, and which she prefaced with the declaration: “For reasons which have nothing to do with literature, I have ceased to collaborate with Willy.” She was free at last.

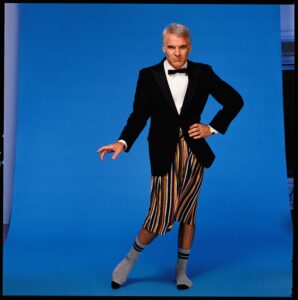

Colette as le petit Faune in Le Desire, La Chimere et L’Amour, c 1906 – her experience in music hall inspired her 1910 novel, The Vagabond (Credit: Alamy)

However, with Willy still retaining the royalties from the Claudine books, Colette was penniless, and to earn money she became a music hall performer. This appealed to her sense of performance and enabled her to play with gender roles: one minute dressed in drag as a besuited man, the next posing with a bare breast in the bodice-ripping pantomime The Flesh. Her experience in music hall inspired her 1910 novel The Vagabond, the highly autobiographical story of performer Renée Néré and a lover she calls “the Big Noodle”, which asks modern questions about the separation of love and sex, and how society seeks to control both through the institution of marriage. (An institution about which, of course, Colette and therefore Renée had great scepticism.) It was The Vagabond that catapulted Colette to literary acclaim for the first time, and the book won three votes for the prestigious Prix Goncourt.

Writing ‘immoral’ books

Colette’s time in music hall might have galvanised her interest in putting herself centre-stage in her fiction. One of her finest examples of this is the late novel Chance Acquaintances (1940), in which Colette the narrator visits a health resort where wealthy women (with fashionably bobbed hair) undergo dubious cures: “nasal douches, steam rooms, flushing the kidneys”. There she meets a husband and wife, the Haumes. Mme Haume is unwell, while M Haume has the appearance of “someone with very few thoughts in his head”. Colette discovers, however, that M Haume is having an affair and that his lover, back in Paris, has gone silent on him. Naturally, this is Colette’s ideal territory, and she agrees to visit his lover in Paris to find out the true story. The plot shows Colette’s appetite for mischief, as well as her enduring interest in the vagaries of the human heart, while M Haume finds that “when intrigue is called into play, a woman never forgets that feminine instinct is the older in guile.”

After Willy, Colette’s second husband, Henry de Jouvenel, could only be an improvement, and as editor of leading newspaper Le Matin, he was also able to publish his wife’s work. But even this came unstuck, as he was forced to abandon the serialised publication of a new book, Ripening Seed (1923), due to the shock it caused readers, and he asked her why she could not write novels that were not immoral.

Colette had relationships with women as well as men, including Mathilde de Morny, the niece of Napoleon (pictured) (Credit: Alamy)

Ripening Seed was the novel that extended Colette’s interest in love, power and sexuality to the crimson red period of adolescence, through teenage friends Philip (impatient to be older) and Vinca (with her eyes of “white and periwinkle blue”). They have been “15 years together as pure and loving twins” and seem likely to develop their friendship, though Philip will find that “possession is a miracle not so speedily accomplished.” But their simple relationship is complicated when Philip is seduced by an older woman: and this too came from life, as at the age of 47 Colette had a relationship with her 16-year-old stepson, Bertrand de Jouvenel. Ripening Seed is a highly sensual novel, revelling in not just bodily pleasures (“ripe lips like fruit scorched by the heat of the day”), but in the smells and sights of the seaside landscape on the Brittany coast.

Ripening Seed was published between Colette’s greatest artistic achievements, Chéri and The End of Chéri. The first book tells of an ageing courtesan, Léa de Lonval, and Chéri, the “very beautiful, very young” man with “hair like the plumage of a blackbird” and “firmly muscled chest” whom she has been educating in the field of love for a number of years. The complications, as ever, arise when Léa decides that it is time for her Chéri to move on. The novelist Amy Bloom called Chéri a “book about the importance of love, the failure of love [and] the way people in love often manage to fail themselves as well as their beloveds”. In the closing lines of Chéri, our hero is “filling his lungs with air like an escapee”. But he is not done with her yet: the companion piece, The End of Chéri, warns us of its ambiguity from the opening lines as Chéri leaves his home, having not thought about Léa for years (“‘Ah! It’s nice out’. He changed his mind at once. ‘No it’s not.'”). And when he enters a society apartment, finding an overweight old woman with “upper arms as fat as thighs”, he recognises her laugh – and we know that all will not end well this time.

“Full of life and laughter”

When she published The End of Chéri, Colette was 53 years old, with great works still to come. The Pure and the Impure, which she considered would one day be regarded as her best book, was a work of reminiscence on a theme of gender and sexuality: Colette had relationships with women as well as men, including Mathilde de Morny, the niece of Napoleon. The book explores relations between men and women, women and women, and covers transvestism as well as homosexuality (or, as Colette puts it in her description of her friend Pauline Tarn, “this poet who never ceased claiming kinship with Lesbos”).

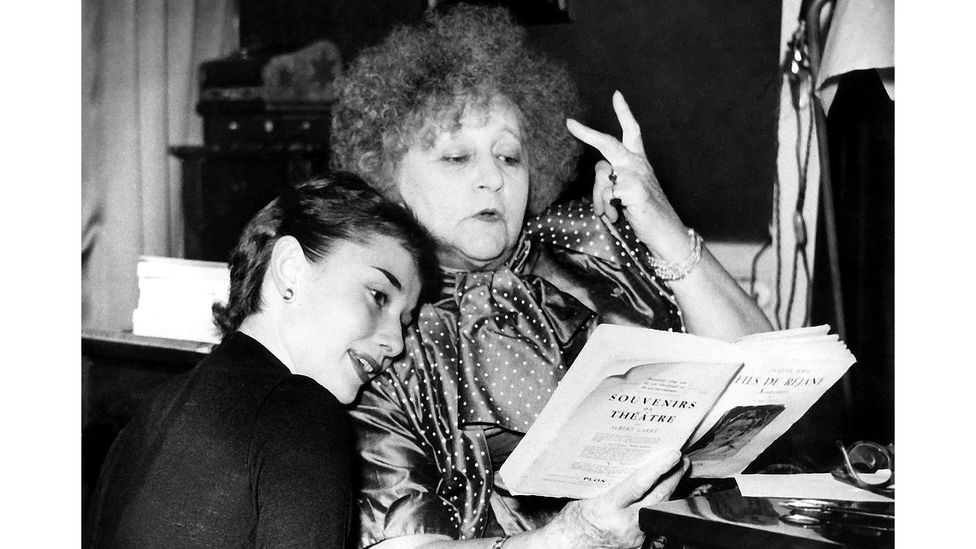

Colette’s best-known book in the English-speaking world is Gigi (1944), which became a celebrated musical starring Audrey Hepburn, and a 1958 film (Credit: Alamy)

But the work she became best known for in the English-speaking world was Gigi (1944), which had familiar elements – the story of a young woman and an older man (the reverse of Chéri), with the young woman being trained as a courtesan. It was one of the last books she wrote, aged 70 and crippled with arthritis, and as a reaction to her circumstances she made it lighter, less cynical and more optimistic than much of her earlier work. (It is perhaps these qualities that have made it so popular.) Gigi became a celebrated stage musical and film; the stage production made a star of Audrey Hepburn, who was personally chosen by Colette for the role.

Colette’s acclaim in France was not always, at the time, matched abroad. Time magazine in 1934 referred to Colette as a “below-the-belt” writer, having previously written that she was a “purveyor to those who like mild aphrodisiacs in print” (while acknowledging that this category included “99.44% of all readers”). Nonetheless, astute readers adored her, including Truman Capote, who puckishly told their mutual friend Jean Cocteau that Colette was the living French writer he most admired (including, that is, Cocteau). Cocteau gallantly set up a meeting in 1947, though Capote – who described the encounter in his essay The White Rose – was so starstruck that he spent much of his time with Colette admiring her collection of antique crystal paperweights.

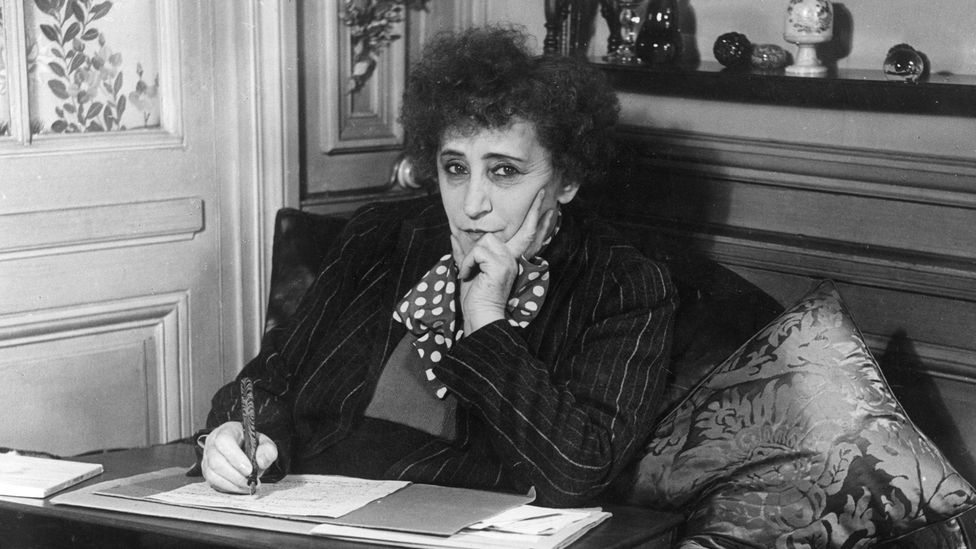

Colette was a huge star in France; she was the first woman to be given a state funeral, after she died in 1954 (Credit: Getty Images)

Back home in France, Colette was a star. She was the second woman to be made a grand officer of the Legion of Honour, and the first to be given a state funeral, following her death in 1954 at the age of 81. Her work did not trouble the reader with politics or world affairs. Her canvas was what Tolstoy called “man’s most tormenting tragedy – the tragedy of the bedroom”. She explored her field without exhausting it or repeating herself, varying her approach as she grew older and more experienced, the perspective shifting like a shadow as the day draws on. Intense and sensuous, her fiction is full of life and laughter, as she proceeded to tell the story of a woman’s life, from childhood into age. That is why, 150 years after her birth, Colette lives on.

Chéri and The End of Chéri, translated by Paul Eprile, are published by NYRB books.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.