The unruly ancient rituals for now

Once a year, on the island of South Ronaldsay, off the north coast of Scotland, the community prepares for two traditional events: The Festival of the Horse and the Boys’ Ploughing Match. Families reach into cupboards and bring down the richly decorated costumes that the town’s girls will wear in a parade through the streets. Passed down through generations, the dresses mimic the trappings of the majestic Clydesdale working horse, with embellished yokes and harnesses, and little woollen fetlocks. Meanwhile, the boys gather on the broad scope of Sands o’ Wright beach where, using exquisitely-made miniature ploughs, they carefully draw “furrows” in the sand. The lad with the most finely tilled furrow wins.

More like this:

– The Scandinavian folk clothing for now

– The ancient enigma that resonates now

– The UK’s mysterious pathways

The Festival of the Horse dates back to the 1800s, when other Orkney villages performed their own versions; today, South Ronaldsay is the last. It is anything but fading: “When I went there, what I found incredibly moving was that the entire community was involved,” says Simon Costin, director of the Museum of British Folklore. “The grandparents, the parents, everyone would be rallying the boys on from the side.” The costumes, old but constantly evolving, are another sign of this resilience. “Over the years, they get increasingly embellished – with pieces of jewellery, Christmas decorations, bells; anything that catches the light.” says Costin. “They become emblems of how the community chooses to express itself.”

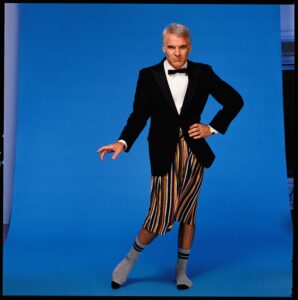

The Festival of the Horse and the Boys Ploughing Match take place annually in the Orkney Islands, Scotland (Credit: Simon Costin)

Today, the Festival of the Horse is just one among many celebrated at Making Mischief, an exhibition opening next week that explores British folk customs and costumes. More than 40 costumes, made, customised and worn by participants will be on display. Curated by Costin and Mellany Robinson, of the Museum of British Folklore, and Professor Amy de la Haye, from the London College of Fashion, the exhibition takes place at Compton Verney, a stately home in Warwickshire already known for its collection of British folk art, including a pull-along toy bull, shop signs and weather vanes in the shape of cockerels and hunting dogs. In Making Mischief, the disciplines – together with loans from the English Folk Dance and Song Society and the English Folk Costume Archive – come together to shine a light on an area hitherto overlooked by museums: the thriving culture of British folk custom.

Those expecting reflections of a bucolic past, of garlanded maidens in halcyon British landscapes, will be disappointed. “Mention seasonal customs and folklore and people get all misty-eyed,” laughs Costin. “They imagine a Victorian version of Merrie England. It’s totally not that.” The Festival of the Horse is fairly sedate but other customs are often rambunctious, even lairy. Take the tradition of the Tar Barrels in Ottery St Mary, every 5 November, during which flaming, tar-soaked barrels, each sponsored by one of the town’s central public houses, are carried, briskly, along the town’s streets. As the day progresses, the barrels get larger; by midnight, they weigh at least 30kg.

Camaraderie and a rowdy competitiveness exist side by side as generations of the same family tout the barrels (“You do get the feeling that a lot of old scores get settled on the periphery,” reflects Costin). The Tar Barrels “proudly perpetuates Ottery St Mary’s great sense of tradition, of time and of history,” proclaims the Visit South Devon website. Folk origins, however, are often lost in time. While the Tar Barrels are believed by some to have been born after the gunpowder plot of 1605, other theories abound: that the burning barrels belong to a pagan ritual that cleansed the streets of evil spirits; that they helped, more prosaically, to fumigate cottages; and that they served as a warning of the approach of the Spanish Armada.

The Jack in the Green May Day festival dates back to the 16th Century and is still celebrated annually in the seaside town of Hastings (Credit: Henry Bourne)

The rowdiness at Ottery St Mary, however, may sound like a tea party compared to the mayhem that is Haxey Hood, in North Lincolnshire . In this night-long event, opposing villages attempt to get hard cylinders of leather – the “Hoods” – into one of the four pubs in either Haxey or the nearby village of Westwoodside. “They lock down into a rugby scrum called the Sway – and the Sway can go on all night,” says Costin. The event takes place in January. “I remember looking across the village and seeing 300 men locked into each other, in this snow-covered field, with the steam rising off them,” he says. “It’s very visceral and archaic. You’re witnessing something primeval.”

Haxey Hood’s (professed) origins lie in the 14th Century, when Lady de Mowbray, the wife of a local landowner, was out riding. As she went over a hill, her silk riding hood was blown away by the wind. Thirteen farm workers chased the hood all over the field, before it was finally caught by one. Too shy to hand it back himself, he gave it to one of the others to hand back to the Lady. Amused, she named the worker who had returned the hood the “Lord”, and the one who had caught the hood, the “Fool”, leading to two of the key characters in the tradition, alongside 11 mercurial Boggins, “custodians of the tradition,” says Hield. “They’re there to keep it safe – but also make it happen.” Lady de Mowbray is then said to have donated land to the workers – on condition that the chase for the hood would be re-enacted each year.

While St Ottery barrellers wear heavy gloves and practical clothing, costume is key in Haxey Hood. The Lord and chief Boggin are dressed in red hunting coats and top hats covered in flowers and badges; the Lord also carries a staff of office, made from twelve willow wands with one more upside-down in the centre, representing the twelve apostles and Judas. His face smeared with soot, the Fool is covered in multicoloured scraps of materials. He leads the procession, beating nearby parishioners away with a bran-stuffed sock and claiming the right to kiss any woman along the way. His welcome speech ends with a traditional rhyme: “hoose agen hoose, toon agen toon, if a man meets a man knock ‘im doon, but doan’t ‘ot ‘im” translated as: “house against house, town against town, if a man meets a man, knock him down but don’t hurt him.”

Deeper meanings

Rowdiness aside, every folk custom – in every community around the world – is unique to its time and place. “People really are passionate about them,” says the University of Sheffield’s Professor Fay Hield, director of the Contemporary Folklore Research Centre. “And the meanings are far deeper than you’d grasp simply by attending. A lot of understanding is held within the community. “Someone coming from the North to an event in the South, for example, wouldn’t get all the references.” What customs do have in common, she says, are the “purposes they serve”: as ways of connecting and responding to the physical, natural and societal worlds around them.

The players in the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, photographed around 1900 by Sir John Benjamin (Credit: Alamy)

“Folk culture refers to the products and practices of relatively homogeneous and isolated small-scale social groups living in rural locations,” wrote George Revill for Oxford Bibliographies. “Thus, folk culture is often associated with tradition, historical continuity, sense of place, and belonging – manifest in song and dance, storytelling and mythology, vernacular design in buildings, everyday artifacts and clothing, diet, habits, social rules and structures, work practices such as farming and craft production, religion, and worldviews.”

Most key of all, says Costin, folk culture is about the people. “It’s not the Lord Mayor’s festival or something run by the county council,” he says. “These are seasonal custom events generated by ordinary people who want to celebrate something particular to them. That’s what delineates a folk custom.”

Horses are a recurring motif in folk tradition. While Making Mischief occupies Compton Verney, Maidstone Museum hosts Animal Guising and the Kentish Hooden Horse, an exhibition uniting the museum’s two old Hooden Horses, from the ancient winter folk custom called the Hoodening, with other similar artifacts, including Morris Dancing horses and Obby ‘Osses. The custom celebrated, the Hooden tradition – like its Welsh counterpart, the Mari Llywd, and Padstow’s Obby ‘Oss – revolves around a wooden hobby horse mounted on a pole and carried by someone hidden by sackcloth. In its contemporary form, the Hooden is accompanied by local people who are also performers in a humorous play, which is typically performed in pubs and at parties.

The Hooden and the ‘Oss, key figures in Padstow’s May Day festival, are reminders that some of folk’s central characters can, at least to outsiders, appear unsettling and otherworldly. “When you’re in the community, you don’t see them as otherworldly,” says Hield, briskly. In 2019, folklorist and historian Ronald M James described the ‘Oss as “a menacing image,” consisting of a large round platform supporting a black apron. “The man who carries the beast puts his head through a hole at the centre of the structure. He wears a mask with a tall, pointed cap. At one end of the platform is a tail and at the other, a stylised head with snapping jaws,” he continued. The ‘Oss’s similarity to a dragon has not gone unnoticed over the years.

The Abbots Bromley Horn Dance is still celebrated today, and is featured in the exhibition at Compton Verney museum (Credit: Henry Bourne)

It was a visit to Padstow as a child that sparked Costin’s long interest in folk custom. “We spent the holidays in Cornwall,” he recalls. “It was May Day, and I was this seven-year-old turning the corner and suddenly seeing this enormous, bizarre, terrifying figure of the ‘Oss, swaying above the crowds and the singing and the music. It was so potent. It was a moment of true magic, when people stepped outside the mundane reality of the day-to-day and became something else.” At events, participants are “no longer the banker, the baker, the nurse, the schoolteacher,” says Costin. “They’ve taken on this persona and they’re engaging in a community-led activity, where all those things are forgotten because they’re celebrating something very powerful.”

Curiosity in folk customs ebbs and flows but, broadly, surges coincide with periods of deep reflection as well as malaise with current systems. “The first revival was around the Industrial Revolution, with the feeling that big industry was having a negative effect and that this way of life was getting lost and needed re-capturing,” explains Hield. The second, better-known, revival took place in the 1960s and 1970s, with a “big rejection of the idea of ‘The Man’. The revival of the 1960s was a shared rejection of mass leadership.”

As Britons wrestle with a perfect storm of societal challenges – from the fallout of Brexit and economic turmoil, to the rapidly encroaching climate and ecological emergencies – today’s revival of interest in folk culture feels like a search for continuity. “In England, there’s currently a real confusion about how to be and how to feel English, yet we still want to do it,” reflects Hield. “It’s a human need to want a sense of pride in our place – and, at the moment, England is an uncomfortable place to be in. People are looking back to an older sense of England in order to reconnect with an identity that’s not bound with more recent political histories.”

The Making Mischief exhibition includes images and artefacts from the world of British folk custom (Credit: Jonathan Cherry and the Simple Things)

While the Making Mischief exhibition celebrates grassroots traditions, it offers a challenge to the idea that these traditions are fixed. “We look at the way folklore retains its potency,” says Costin. “Because, if these things die out, it’s because they’ve lost their relevance. People don’t want to keep these customs in amber and ossified. These are living traditions.” Thus, for example – just one among many – in the early 20th Century, Padstow saw the introduction of a second ‘Oss, known as the Peace or Armistice ‘Oss. Each year, a new script is written for The Hoodening, featuring themes such as death and resurrection and peppered with references to local and international news.

Making Mischief highlights the rise of all-female Morris sides (including Gloucestershire’s Boss Morris) and the inclusion of LGBTQ+ performers in some customs; Costin himself is one of the instigators of the Gay Bogies collective of Hastings. But nothing highlights the resilience of the British folk custom better than this year’s speech from the Fool at Haxey Hood: “This game is 664 years old today. And like all good traditions, it’s been modern enough to last for the time, but old-fashioned enough to last forever. And it will last forever!” he roared, to cheers, laughter and the trill of mobile phones. “There are lots of things that will remain, like Chris Leighton’s home brew, and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, God Bless Her. Long live the King! Tonight, we have roast pork, but we also have a nut and mushroom roast for vegetarians and vegans. What a diverse set of people we are!”

Making Mischief: Folk Costume in Britain is at the Compton Verney museum from 11 February to 11 June 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.