Why 5 October, 1962 changed Britain

“Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three… / Between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban / And the Beatles’ first LP.” So wrote Philip Larkin in his 1967 poem Annus Mirabilis, reflecting on how British society was transformed in the early 1960s. This was only the beginning of a liberating cultural revolution that would eventually sweep the world, with “swinging” London as its wellspring. Time Magazine correspondent Piri Halasz captured the mood vividly; “In a decade dominated by youth, London has burst into bloom. It swings; it is the scene… The city is alive with birds (girls) and Beatles, buzzing with mini cars and telly stars, pulsing with half a dozen separate veins of excitement,” she wrote in April 1966. “London is not keeping the good news to itself… London is exporting its plays, its films, its fads, its styles, its people.”

More like this:

– Why Bond is the ultimate spy hero

– The Beatles’ greatest album

– The poster girl for the swinging ’60s

Chief amongst these cutting-edge cultural exports were the music of The Beatles and the films of James Bond. These two great pop cultural phenomena would help to redefine Britain and Britishness for a receptive global audience. They were also, incredibly, born on the same day – 5 October 1962 – with the release of the first Beatles single, Love Me Do, and the premiere of the first James Bond picture, Dr No. The serendipity of this moment probably passed entirely unnoticed at the time, but the world we inhabit today is still enjoying its aftershocks. As Ian MacDonald writes in Revolution in the Head, his seminal history of The Beatles’ records and the sixties, the release of Love Me Do “blew a stimulating autumnal breeze through an enervated pop scene, heralding a change in the tone of post-war British life matched by the contemporary appearance of the first James Bond film, Dr No…”

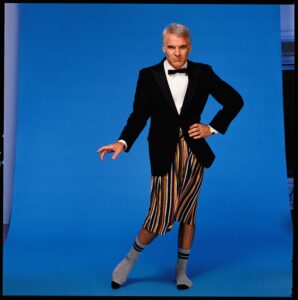

When they emerged in 1962, The Beatles shook up the whole notion of who could be great artists (Credit: Alamy)

Within Britain, the years immediately following World War Two were marked by austerity, while the Suez crisis of 1956 made it painfully clear that the UK was no longer the political or military superpower it had long prided itself on being. “Britain at that point needed a new story and a new way of understanding itself,” John Higgs, author of Love and Let Die: Bond, The Beatles and the British Psyche, tells BBC Culture. “During the previous couple of centuries, we knew what we were – a global empire. The story we told ourselves was one of Britannia ruling the waves, and the sun never setting on the British Empire. Our sense of identity had gone. We needed a new one. This is where Bond and The Beatles – and the embrace of the modern – came in. They gave us examples of who we wanted to be.”

The sudden fall of the imperial status quo, along with a growing consumer society, set the stage for a radical transformation of British values, spearheaded by popular culture. As working-class, northern English musicians with little formal training, The Beatles defied all preconceived notions of where great art could emerge. Their appearance was startlingly androgynous, their accents undiluted, and their followers adoring. “The band’s unique sound and image suggested to young audiences that success did not mean following a prescribed path,” Christine Feldman-Barrett, author of A Women’s History of the Beatles, tells BBC Culture. “The Beatles demonstrated that trying something new and channelling your talents – no matter your background or who you were – could be a winning combination. That was a powerful message in 1962. It seemed to herald the future. And given the way that young women featured in the band’s early history – including their devout, female fanbase – it was a future that also included women as key players. In this new, vibrant world The Beatles symbolised and implied, everyone mattered, and everyone was welcome to take part in the fun.”

Love Me Do peaked at 17 in the UK charts, the first step in a meteoric rise to unprecedented heights of celebrity. Much of the British establishment had no idea what had hit them. The Conservative politician Ted Heath, then-Lord Privy Seal and future Prime Minister, snobbishly remarked in 1963 that he found it hard to recognise the Beatles’ Liverpudlian accents as “the Queen’s English”. John Lennon shot back, “We’re not gonna vote for Ted”. Two years later, Heath’s party had duly been voted out of office and The Beatles were at Buckingham Palace to collect their MBEs.

Bond and the Beatles’ affinity

Like The Beatles, the cinematic James Bond established a new model for British life. Ian Fleming’s novels, beginning with 1953’s Casino Royale, had depicted Bond as a broadly reactionary figure. It was the casting of Sean Connery, a working-class actor and former bodybuilder from Edinburgh, that transformed the big screen Bond into a dynamic and modernising hero fit for the sixties. As the producer Albert R “Cubby” Broccoli reflected in his autobiography, “Physically, and in his general persona, he was too much of a rough-cut to be a replica of Fleming’s upper-class agent. This suited us fine, because we were looking to give our 007 a much broader box-office appeal”. The modern action hero was consequently born, combining a classically English sense of style with a tough, transatlantic insouciance, entirely divorced from the effete and aristocratic “gentleman heroes” of earlier British thrillers like Bulldog Drummond. Some cinemagoers were as confused by Connery’s regional accent as Ted Heath had been with The Beatles’. “If you look at the reviews of Dr No, the American reviews, they can’t place his accent, they think he’s Irish,” Llewella Chapman, author of Fashioning James Bond, tells BBC Culture.

Connery’s first scene in Dr No is surely one of the finest character introductions in all of cinema, unveiling our stylish hero at the baccarat table in Mayfair’s exclusive Les Ambassadeurs Casino. “The audience is slowly introduced to the character, framing the quality of his dress and location before you even see Connery’s face. He’s defined by a penchant for quality, from clothes and casinos to his relations with very beautiful women,” says Chapman. As a suave and sexually liberated citizen of the world, Bond was the perfect fantasy figure for a new age of jet travel and the contraceptive pill. Indeed, director Terence Young felt that the secret to his film’s financial success was little more than timing. “I think we arrived not only [in] the right year, but the right week of the right month of the right year,” he is quoted as saying by James Chapman in Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films.

Sean Connery’s tough-guy James Bond was very different from the secret agent imagined in Ian Fleming’s novels (Credit: Alamy)

It might seem obvious why the exotic adventures of Bond and the exhilarating melodies of The Beatles appealed to teenagers of post-war Britain, but their success across the globe is probably more vital to their enduring legacy. They represented a British identity that was younger and, crucially, friendlier than the pith-helmeted colonialists who had exported the British way of life for the previous few centuries.

What they symbolised about Britain

The Beatles had already conquered Europe by the time they began their invasion of the US charts in early 1964, and they soon moved on to Oceania and Asia. Thanks to their influence, the youth of the world adopted mop-top haircuts and the modish styles of London’s West End tailors, but this cultural exchange was not a one-way street. Rock-and-roll music had originated, after all, as an African-American artform – an influence that John Lennon keenly emphasised in a 1972 interview with African-American weekly magazine JET. From 1966, The Beatles’ embrace of Indian culture, largely on the initiative of lead guitarist George Harrison, helped to popularise practices like yoga and meditation across the western world.

The band’s open-minded embrace of the new and the radical was their strength, but their subversive influence, particularly on the youth, was not always welcome. The Soviet Union banned Beatles records, while the Ku Klux Klan staged burnings of them. In Japan, protestors took offence when the Beatles commandeered the sacred Nippon Budokan as a concert venue, and death threats were made. Even James Bond himself, the self-appointed arbiter of good taste, complained in a scene from the third Bond film, 1964’s Goldfinger, that drinking warm champagne was “as bad as listening to The Beatles without earmuffs”. But it was pointless trying to hold back the tide – The Beatles were blazing an unstoppable trail of youthful energy that would be followed by generations of pop stars.

James Bond’s position as a symbol of Britishness is a little more problematic. As a violent agent of Her Majesty’s Government, Bond represents an explicit projection of imperial power, conveniently arriving at just the time that Britain’s ability to wield such power in the real world was on the wane. This is arguably more explicit in Dr No than subsequent instalments, as Bond’s mission takes him to Jamaica – then in its last months as a British colony. The idea that MI6 had the practical or moral authority to police the world was already the stuff of fantasy by 1962, but it was a vision many found appealing, even reassuring, in the face of Britain’s actual decline against the ascendent United States. As Jeremy Black argues in The Politics of James Bond, 007’s “unflappable competence offered protection against the schemes of villains and, more generally, served both to shore up traditional notions about Britain and to support notions of an effective new Britain”.

Furthermore, the aspirational appeal of James Bond’s lifestyle won him admirers across the world. Time Magazine observed in June 1965, “There seems to be no geographical limit to the appeal of sex, violence and snobbery with which Fleming endowed his British secret agent,” calling him, “the biggest mass-cult hero of the decade”. The term “Bondmania”, derived from the adjacent “Beatlemania”, described the clamour for Bond films and their related products, from soundtrack LPs to children’s toys and 007-branded cufflinks and shirts. Bond’s world of luxury and hedonism no longer seemed the preserve of an oppressive elite, as Tony Bennett and Janet Woollacott argue in Bond and Beyond; “in the context of ‘swinging Britain’, Bond produced a mythic encapsulation of the then-prominent ideological themes of classlessness and modernity,” they write, “a key cultural marker of the claim that Britain had escaped the blinkered, class-bound perspective of its traditional ruling elites and was in the process of being thoroughly modernised as a result of the implementation of a new, meritocratic style of cultural and political leadership; middle class and professional, rather than aristocratic and amateur.”

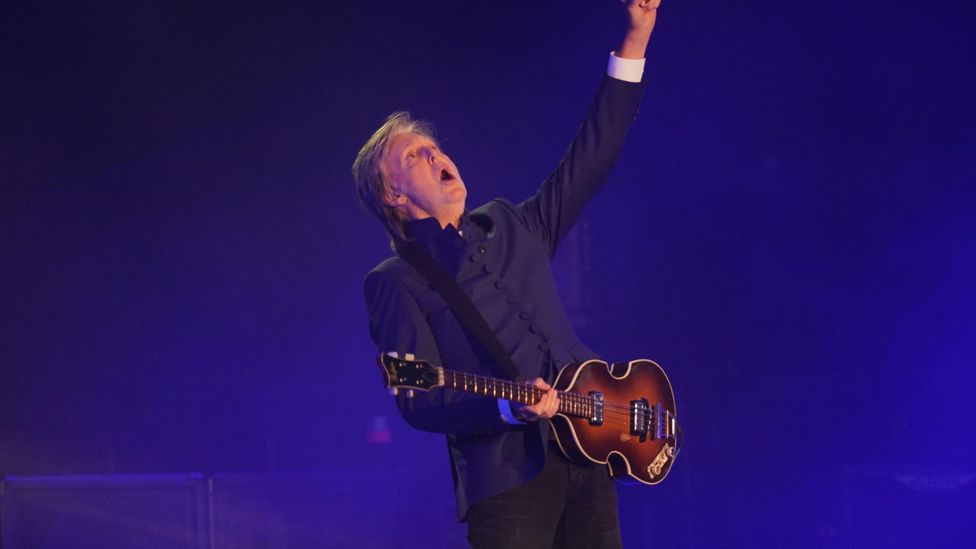

Paul McCartney’s triumphant, Beatles-filled set at this year’s Glastonbury is testament to the sheer durability of the Beatles’ appeal (Credit: Alamy)

The Beatles, meanwhile, became a lodestar for a generation of musical talent. In a recent BBC documentary series, My Life as a Rolling Stone, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards acknowledge the influence of The Beatles’ early records, and particularly Love Me Do, in inspiring them to write their own pop songs. Wherever The Beatles travelled, others would follow; for two years following their momentous appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964, the US charts were dominated by British artists who looked and sounded an awful lot like the fab four.

The mid-1960s also saw an explosion of espionage-themed films and television, self-consciously produced in the James Bond mould. Some, like Sidney J Furie’s The Ipcress File and Martin Ritt’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (both 1965), distinguished themselves with a more realistic tone than that of the Bond films. Others, such as the Matt Helm series (a star vehicle for Dean Martin), were less ambitious. As Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury write in their biography of the Bond films, Some Kind of Hero, “If James Bond represented The Beatles of the genre, Matt Helm might be considered The Monkees.” Even The Beatles grabbed for a slice of Bond’s pie, their 1965 film Help! functioning as a 007 spoof. This trend reached its cynical apotheosis with the 1967 Italian film OK Connery, starring Sean Connery’s brother Neil.

Six decades later, however, and it’s still Bond and The Beatles who remain the foremost icons of their era. James Bond is now the longest-running film franchise in history. The 25th instalment, No Time to Die, arrived in cinemas in 2021 and became the highest-grossing release since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. A few months later in June 2022, Paul McCartney headlined Glastonbury Festival with a setlist dominated by Beatles hits. The secret to this longevity is really no mystery. “Ultimately, it must be because they are good,” says John Higgs. “Artists and creators create work which they cast into the great lake of culture, and successful works float for a moment before sinking down into the dark depths. It is rare for things to bob back up again, and the things that do have to be not just of their time, but timeless. They need to speak to people across decades. That can only happen when things are good.”

The Beatles themselves might have recoiled at the idea that the peace-and-love mantra of their music had anything to do with the violence and destruction wrought on screen by 007. But together, these two fashionable institutions wove a new national myth that Britain was not only benevolent and exciting, but cool. From the ashes of former imperial power had risen a cultural behemoth.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday