Why is the US banning children’s books?

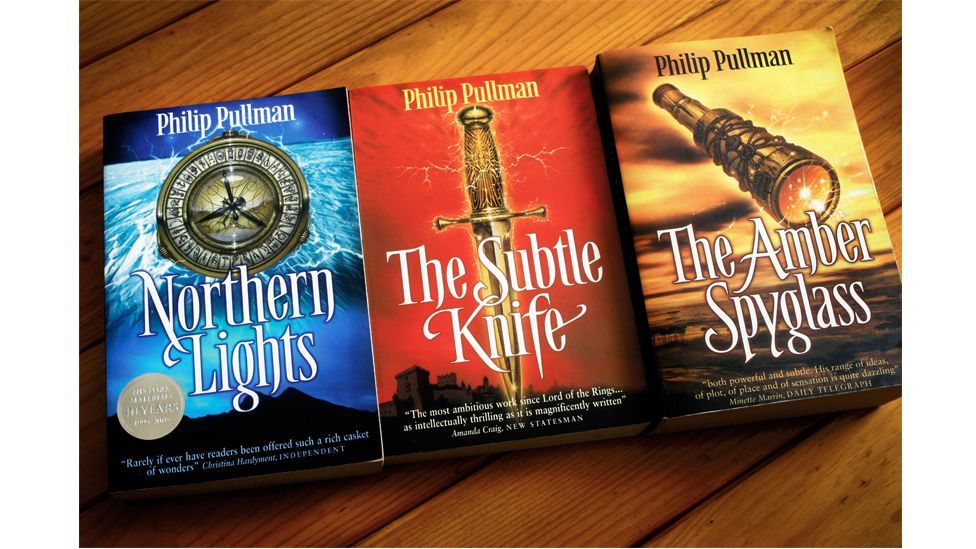

Philip Pullman’s widely acclaimed fantasy novel Northern Lights has been voted sixth in the BBC Culture 100 greatest children’s books of all time poll, and Pullman is the number one living author on the list. Yet when it was first published in the US in 1996, the novel – known in the US as The Golden Compass, and the first book in the trilogy His Dark Materials – was in some parts of the US banned, and by 2008 was the second most challenged book in the US.

Read more about BBC Culture‘s 100 greatest children‘s books:

– The 100 greatest children’s books

– Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

– The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

#100GreatestChildrensBooks

Northern Lights won the Carnegie Medal for children’s fiction in the UK in 1995, and in 2019 Pullman was knighted as well as honoured with the 2019 JM Barrie award, marking a “lifetime’s achievement in delighting children”.

His Dark Materials, the 1990s fantasy trilogy by Philip Pullman, was challenged by a vocal minority in the US (Credit: Alamy)

Yet the world view presented in Northern Lights and the rest of the trilogy – considered by some as atheist in sentiment – proved too much for some vocal minorities in the US. The American Library Association’s 2008 banned book list identified the title as the second-most challenged book in the country, with objections coming from the Catholic League. In fact the whole trilogy caused outrage in some sections of the US, while in the UK, columnist Peter Hitchens stated that Pullman was “the anti [CS] Lewis, the ones atheists would have been praying for, if atheists prayed.” (CS Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is also in the BBC Culture poll’s top 10).

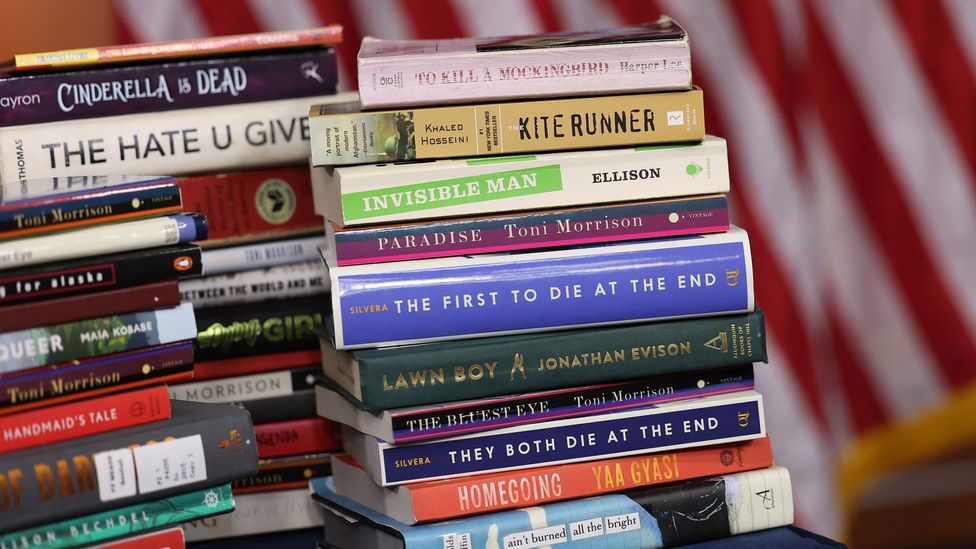

The banning of Northern Lights could be considered a precursor to censoring books for “moral”, world view or religious reasons. Now the banning and challenging of books in the US has escalated to an unprecedented level. The ALA documented an unparalleled number of reported book challenges in 2022, more than 2,500 unique titles, the highest number of attempted book bans since the ALA began tracking censorship data more than 20 years ago. Books for young people that have been targeted for topics such as race, gender and sexuality include Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, George M Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and Jonathan Evison’s Lawn Boy.

“Ultimately, attempts to ban books are attempts to silence authors who have summoned immense courage in telling their stories,” ALA president Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada tells BBC Culture. “Most books that people object to are by or about LGBTQ+ individuals or people of colour. Those books are on library shelves because someone in the community wants to read them. It’s the job of a librarian to provide access to those authors and stories, whether they mirror the experience of a reader or shed light on an unfamiliar perspective.”

She adds, “Americans enjoy the freedom of expression and the freedom to engage with others’ expression. We get to choose the books and ideas we want to engage with, but we don’t get to decide what our neighbours can read and think. We don’t get to silence stories that we don’t like.” The movement to ban books is driven by a vocal minority demanding censorship,” Kasey Meehan, director of PEN America’s Freedom to Read project, tells BBC Culture. “This school year saw the effects of new state laws that censor ideas and materials in public schools, an extension of the book banning movement initiated in 2021 by local citizens and advocacy groups. These efforts to chill speech are part of the ongoing nationwide campaign to foment anxiety and anger with the goal of suppressing free expression in public education.” Bans occurred in 32 states, affecting four million children and young people. The surge of banned books includes more titles that touch on violence and abuse, health and wellbeing, or instances or themes of grief and death.

Some of the banned books from various US states and school systems, photographed in March 2023 (Credit: Getty Images)

Reasons given by challengers include “gender ideology propaganda”, “transsexual material”, “embracing trans ideology which is an assault on girls/women”, “sexual misconduct”, “drug/alcohol use”, “LGBTQ content”, “violent”, “anti-police”, “racist”, “obscene”, “paedophilia”, “grooming”. “In the past 10 to 13 years, the LGBTQ books have gotten very sexually graphic,” Jennifer Pippin, a Florida mother and book challenger, and founder of Moms for Liberty, told the Washington Post. The concern over LGBTQ books is not homophobia, she said, but the “sexually explicit” nature of the texts.

Censorship and sensibility

“While the book banners are a minority of the population, they are a vocal minority… and an organised one, determined to impose their wills on every level of governance,” author Jonathan Evison tells BBC Culture. Evison’s novel Lawn Boy, about a young Mexican-American yard worker who struggles to forge his way in working-class Seattle, is seventh on the ALA most-banned list. “Thus, it is very important that we be diligent and organised in our efforts to defend free speech.”

Ninety percent of the challenges in 2022, according to the ALA study, were lists compiled by organised censorship groups (40 percent were of 100 books or more). “The book banners have developed a kind of playbook – a list of targeted books, and the offending passages from each book,” Dave Eggers, author of, most recently, the “all ages” novel, The Eyes and the Impossible, tells BBC Culture. Eggers visited Rapid City, South Dakota, after his novel The Circle was banned in high schools there, and all the school district’s copies destroyed.

On 17 May, George M Johnson, whose memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue navigates boyhood and adolescence from the perspective of a queer black boy, joined PEN America, publisher Penguin Random House, several other authors, and parents of two children in the school district, to file a lawsuit in Florida to fight against a county that removed books, violating the first amendment and the 14th amendment, and asking for books to be returned to school library shelves where they belong.

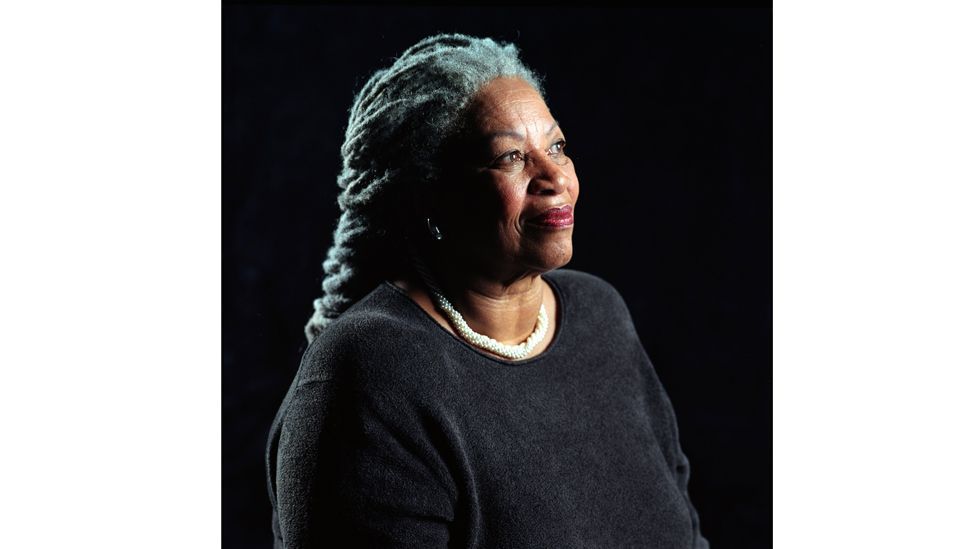

Toni Morrison’s 1970 coming-of-age novel The Bluest Eye is among the young adult books being challenged (Credit: Getty Images)

“What gives me hope,” Johnson tells BBC Culture, “is that the majority of the country is against book bans. The fact that the bans are activating students to fight for their rights to have books. And that we are winning in a lot of counties, and keeping the books on shelves. We are galvanised and organised and ready to continue this fight for as long as it takes. Furthermore, the banning of books has not stopped publishers from allowing more stories to be written. Eventually, there will be so many stories that you can’t ban them all.”

Nobel laureate Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, a coming-of-age story that explores the effects of racism on a young girl’s psyche, is third on the ALA’s most challenged list. Morrison once explained that the book’s title was inspired by black childhood friend who, at age 11 told her she had been praying for two years for blue eyes. “This kind of racism hurts,” Morrison said. “This is not lynchings and murders and drownings. This is interior pain.”

As BBC Culture honours the 100 greatest children’s books of all time, it’s a good moment to envision the children’s books still to be written (and illustrated), the myriad of voices still to be heard, the stories still to be told. And to consider Morrison’s eloquent argument against book banning in Burn This Book, the PEN America anthology she edited. “The thought that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing underground, essayists’ questions challenging authority never being posed, unstaged plays, cancelled films – that thought is a nightmare. As though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.”

Read more about BBC Culture‘s 100 greatest children‘s books:

– The 100 greatest children’s books

– Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

– The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

#100GreatestChildrensBooks

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.