An ‘unapologetically Indian’ universe

A video depicting an otherworldly India flashed across screens in New York’s Times Square in 2022. In one scene, a warrior resembling Lord Ganesha appeared in Transformers-esque battle armour. Elsewhere, a tower in the style of a minaret from the Mughal era glimmered with gold and lasers. These powerful visuals featured in a trailer for Indus Battle Royale, a video game set in space and based on the Indus Valley Civilisation – one of mankind’s oldest urban societies, which arose on the Indian subcontinent around 3000 BCE.

More like this:

– The stories hidden in an ancient craft

– The sci-fi genre offering radical hope

– The music most embedded in our psyches?

Combining Indian mythology and architecture with science fiction, Indus Battle Royale is one of the latest manifestations of a philosophy known as Indofuturism – an aesthetic, a genre and a narrative that envisions what India could look like in the future. These visions, whether expressed through science fiction, music or art, are rooted in staples of traditional Indian culture such as spirituality and folk customs. But they’re also universally appealing, thanks to provocative design, cutting-edge technology, captivating sonics and their emphasis on diversity and self-reliance.

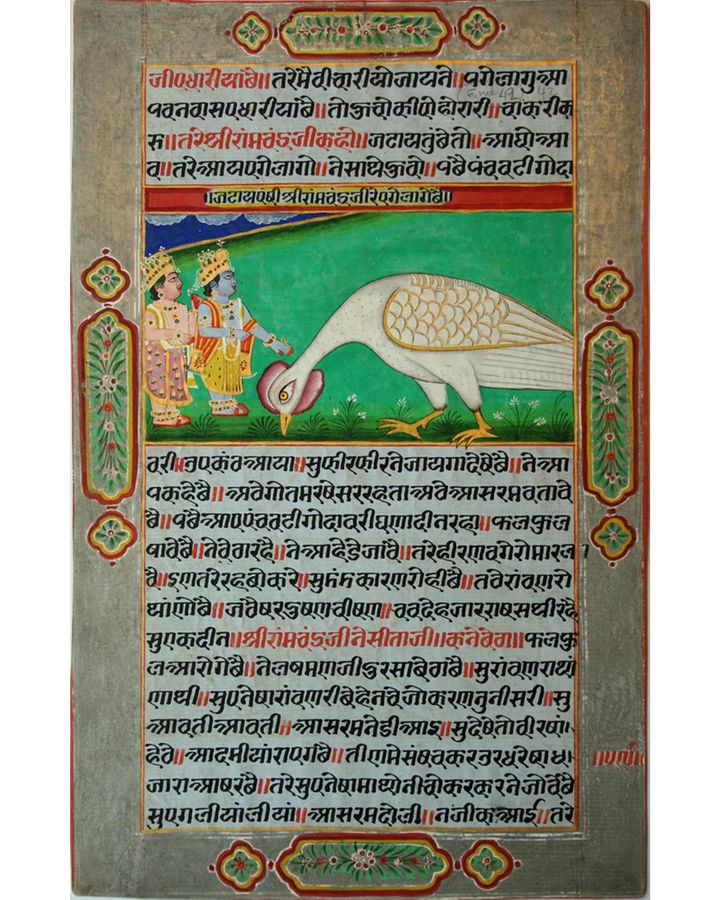

Based around the idea of the Indus Valley Civilisation advancing to a planet in outer space instead of going extinct, the game alludes to various mythological icons, including the eagle demi-god Jatayu, traditionally a symbol of bravery, who is shown with the addition of phoenix wings. “Indofuturism is about setting your mind free and imagining a world that is unapologetically Indian,” Roby John, co-founder of SuperGaming, the company behind Indus Battle Royale, tells BBC Culture.

The video game Indus Battle Royale is based around the idea of an ancient civilisation re-locating to another planet (Credit: Indus Battle Royale)

Indofuturism isn’t new but it is increasingly prevalent in popular culture. More and more creatives are concocting alternative realities based around Indian spirituality and folk customs, in a process that challenges Western visions of the future. “The discourse around futurism is often deeply rooted in Eurocentric ideas of the world,” says Sarathy Korwar, a London-based jazz musician who describes his latest album, Kalak, as “an Indofuturist manifesto”. Just like Afrofuturism, “Indofuturism is moving the focus to the Global South,” Korwar tells BBC Culture.

Other non-Western futurisms include Gulf Futurism, Sinofuturism, Indigenous Futurisms and of course, Afrofuturism, the catalyst for it all. Each of these philosophies possess varying visual languages and motivations but they all lay their own claim to modernity using an indigenous methodology. In Indofuturism, that means applying localised knowledge to alternative realities. On Kalak, Korwar’s polyrhythms are informed by India’s cyclical understanding of time. “In South Asia, culturally, we envisage our relationship to the future and the past in ideas of cyclicality,” the percussionist explains. “Time doesn’t have to flow in a line but can be understood to flow in a circle”. Korwar describes his music as “circular” alluding to a composition technique in which a song’s beginning and end are indistinguishable. This is evident on Kalak’s single, Utopia Is a Colonial Project, in which glistening synth lines both start and end the track. Music’s “inherent hierarchy”, ie reading notes from left to right and top to bottom, pushed him to think about a circular notation system instead.

The word Kalak itself is also a palindrome, echoing the idea of continuous loops, while the album artwork features a circular symbol of sacred geometry. Several strains of Indian folk music are usually performed by a group of musicians sitting in a circle, and this communal aspect of music-making was another influence on Korwar, who describes his style as “future folk”. In this setting, a player’s role is fluid as they can be an audience member and performer at the same time, he explains. All these references are his way of breaking up the Western construct of linearity.

Origins of Indofuturism

It’s hard to locate the exact origins of Indofuturism. Some experts point to early Indian modernists such as poet and thinker Rabindranath Tagore who, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, sought to install a new form of education in West Bengal. His school, Santiniketan, integrated indigenous knowledge, nature, art and pan-Asian beliefs in an effort to create a curriculum that would surpass the British colonial model, and create a new generation of Indian free-thinkers. Begum Rokeya, a writer and political activist, also embodied Indofuturism in her early fiction. Her 1905 short story Sultana’s Dream depicts a society ruled by women who invent solar ovens, flying cars and cloud condensers that offer abundant clean water. Published at a time when widows were burned alongside their deceased husbands, the fictional work is an influential critique of patriarchal science, and one of India’s first examples of feminist science fiction.

A folio dating from 1820-40 depicts the eagle demi-god Jatayu, who also features in current Indofuturist imagery (Credit: Alamy)

Just as Afrofuturism seeks to liberate the black diaspora from past and present-day socio-political issues, the examples of Tagore and Rokeya show how Indofuturism was also born from frustrations with the status quo. For contemporary creators, a lack of Indian representation on the global stage was a key motivator. Antariksha Studio, a media company that has produced Indofuturist games since 2016, entered the space in order to boost India’s position in gaming. “India has always been very poorly represented, as well misrepresented,” says Antariksha Studio co-founder Avinash Kumar. Popular video games such as Tomb Raider and Assassin’s Creed all have chapters and entire games set in India. But, says Kumar, “the irony is that while India might be the subject as well as the base for creating these productions, it is forgotten in the actual narrative beyond stereotypes.”

By contrast, Antariksha Studio’s worlds are rooted in Indian heritage, with added steampunk motifs. One game, Antara, features a biomorphic aircraft designed like a dragonfly with the metallic texture of Chola Bronze, a type of artisanship from the 9th Century. Based around Indian space exploration and aeronautics, Antara sees space travel as a way to restore harmony among cultures, as opposed to the conquest-and-survival narratives pervasive across mainstream media. Elsewhere in India is another game about conserving lost artefacts of traditional culture, and follows Meenakshi, an out-of-work cyborg built for preservation work. One character is seen carrying a hybrid instrument that combines an antique sarod – a lute used in classical North Indian music – with a synthesiser to create what’s described as “electro-classical” music.

There is a difference between general science fiction set in India and science fiction under Indofuturism. The former typically superimposes Indian storylines on to Western representations of futurism – think flying cars, mass surveillance and towering skyscrapers. Examples include Ramayan 3392 AD, a comic book about Hindu gods in a post-apocalyptic future, or Bollywood films about aliens. Indofuturism, on the other hand, aims to create a future that doesn’t fall victim to Western tropes. The crew behind Indus Battle Royale were all too aware of juxtaposing Indian culture on to standardised aesthetics. To avoid it, they invested their energies in world building. “This meant envisaging an entire civilisation,” and not just using existing imagery, Roby John explains.

Western visions of the future carry political connotations, so reproducing them in the context of the Global South could lead to unconscious bias, warns critic Rahel Aima, who has written extensively about non-Western futurisms. Techno-orientalism, for instance, is an aesthetic that refers to Asian visuals such as neon signs and mega-corporations in Hollywood’s brand of cyberpunk. It originated in the 1980s – amid fears in the United States about an increasingly powerful Japanese economy – and spread negative representations of North Asia.

Musician Sarathy Korwar’s album Kalak – artwork, pictured – is based around a circular notion of time and music (Credit: Sijya Gupta and Fabrice Bourgelle)

There has been a recent backlash against the term Indofuturism. “Indofuturism looks to Hindu mythology and that just feels increasingly loaded,” says Aima. As a result, cultural theorists are now gravitating towards the more inclusive term South Asian futurisms, which encompasses Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Nepal as well as India.

Some manifestations of the genre point to a more pessimistic future, an indication perhaps of the country’s current complex political climate. Leila, a 2017 book, for example, explores religious fundamentalism and air pollution – both present-day problems. Indofuturism is likely to keep evolving as the world’s largest democracy deals with climate change and political tensions. For the most part, though, Indofuturism is imbued with positivity. While it doesn’t shy away from problems, it does so with a healthy desire for transformative change.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.