Five ways to be calm and why it matters

Is calmness a passive state of being, involving numbing oneself to what’s really going on? Is it in some cases unnatural – sociopathic even? Or is a sense of tranquillity one of the greatest qualities we can have? Here are five ideas about calmness, from the philosophy of serenity, to the music, art and poetry that can make us feel peaceful – and how to find our “flow”.

More like this:

– Eight nature books to change your life

– The sci-fi genre offering hope

– Inside Japan’s most minimalist homes

Stoic serenity

“Stay calm and serene regardless of what life throws at you,” advised the Roman philosopher Marcus Aurelius. Sounds easier said than done, you would think. But in fact, the Stoic Aurelius had a knack for making calmness seem easy to achieve.

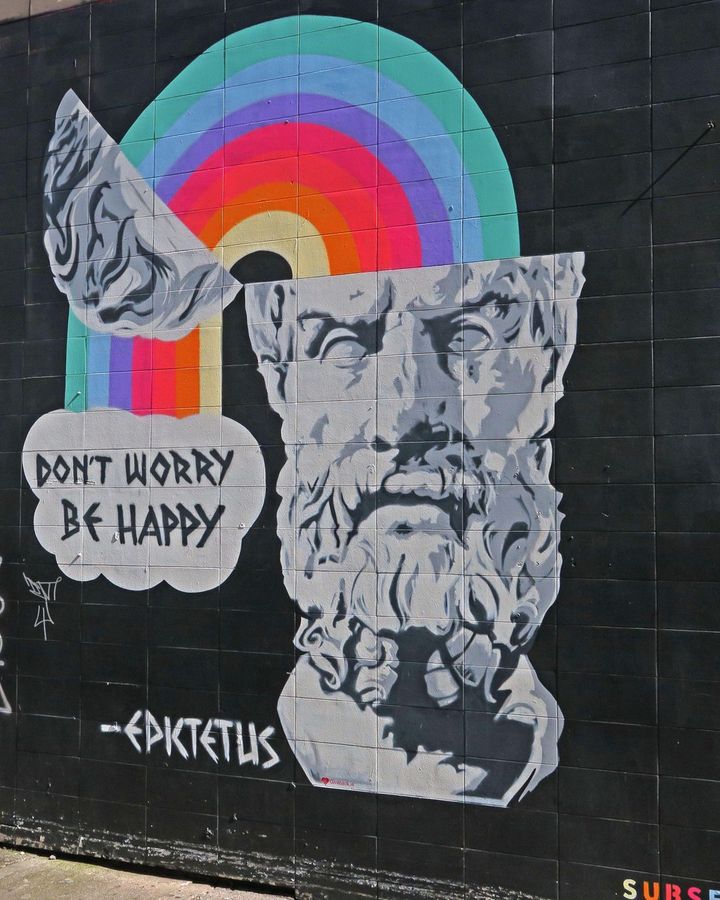

The philosopher Epictetus and other Stoics believed that finding calm was essential – and within our control (Credit: Alamy)

Aurelius’s famous work Meditations is, according to John Sellars – author and Reader at Royal Holloway, University of London – all about “putting our everyday cares and concerns into wider perspective”. As emperor of Rome, Aurelius faced huge pressures but, Sellars tells BBC Culture: “He often reminds himself how brief his life is compared to the vastness of time, and how small it is compared to the whole of the cosmos.”

In line with his Stoic life view, Aurelius also reminds himself constantly that “whatever frustration or negative emotions he might be feeling are ultimately the product of his own judgments or interpretations about situations, and so, as a consequence, things within his power to control,” says Sellars.

But why the emphasis on being calm? Is it really that important to find peace? In the Stoic mindset, it seems, calmness is everything – it is strength. As Aurelius writes in Meditations: “The nearer a man comes to a calm mind, the closer he is to strength.”

Sellars explains: “Calmness is essential to living a good, happy life, Marcus and his fellow Stoics would insist. This is because a disturbed or troubled mind isn’t going to be able to make sensible, rational decisions. The person in the grip of violent emotions, for instance, literally isn’t thinking straight. They have been overcome and may act impulsively or violently. In order to make good decisions we need a calm frame of mind so that we can pause and reflect before behaving merely reactively.”

According to the Stoics, we just need to see that calmness is within our control. Whatever is going on in the world, “it all depends on our judgments and interpretations of situations, not the situations themselves,” explains Sellars. The philosopher Epictetus, he adds, who was Aurelius’s primary influence, wrote: “When we are frustrated, angry or unhappy, never hold anyone except ourselves – that is, our judgements – accountable.”

This core Stoic idea was, says Sellars, “a huge influence on the founders of modern cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and its effectiveness has been proven by the many studies of CBT that have been made”.

The electronic album Stellar Drifting by George FitzGerald is inspired by the cosmos – Setting Sun is a particularly tranquil listen (Credit: George FitzGerald)

Electronic escape

From supposedly soothing pan pipes to ambient rainforest sounds, we are all accustomed to the stock idea of soundscapes as a calming backdrop. But of course the sounds that each of us find restful are by definition a personal thing, and there is no one-size-fits-all soundtrack that will promote peacefulness for all.

Just as the Stoics emphasised perspective and how small each of us is compared to the whole of the cosmos, electronic music artist George FitzGerald looked to the universe and the stars for inspiration for his 2022 album Stellar Drifting. The musician told MusicTech: “To me, [space] represented the furthest point away; the grandest vision of humanity.” FitzGerald spent time in New Mexico driving in the desert and stargazing. “Space gets you out of yourself. It reminds you that we’re tiny and insignificant.”

He took images of the universe collected by Nasa and, by feeding them into new software programmes, converted them into sounds, which he then developed into the 10 tracks on the album. He also used audio recordings from probes that were floating around the solar system.

Electronic, garage and house music have for decades been a form of escapism, first evolving in the interesting margins of society, and uniting disparate groups. And according to FitzGerald, the stars in the sky are an escapism, one that connects all of us. Probably the most calming track on the album is Setting Sun, to be enjoyed not necessarily on a busy dancefloor, but rather lying on a sofa or standing on a hillside, contemplating the vastness of the universe – and our own insignificance.

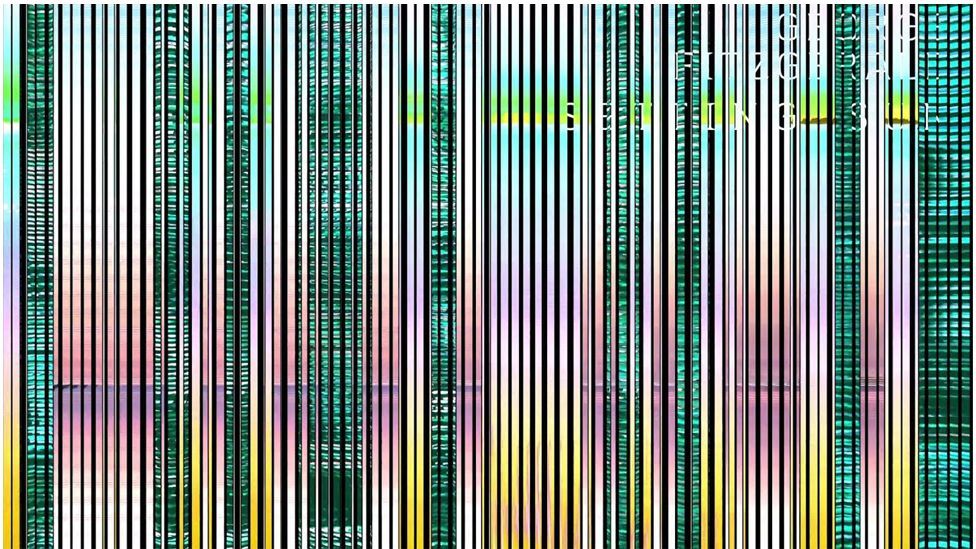

Hilma af Klint’s The Ten Largest, Group IV, No. 3 Youth 1907 will feature in an upcoming exhibition at the Tate Modern (Credit: Tate/ Courtesy of the Hilma af Klint Foundation)

Art of tranquillity

Likewise in visual art, one viewer’s tranquil, meditative experience is another’s intense psychodrama. The New Yorker describes the work of Swedish artist Hilma af Kilmt as “fearfully esoteric” and resonating with a “restlessly searching mood in present culture”. For other spectators, masterpieces such as The Ten Largest, Group lV, No. 3 Youth 1907 are quintessentially peaceful in their enigmatic otherworldliness.

A Swedish mystic and painter, Af Klint developed her own lexicon of pastel-hued shapes several years ahead of other more feted abstract artists. An exhibition this April at London’s Tate Modern will explore her work alongside that of Piet Mondrian. “At the heart of both of their artistic journeys was a shared desire to understand the forces behind life on Earth,” says the Tate.

Af Klint began her career as a landscape painter, inspired by nature, and then her work began to represent natural forms that veered towards abstraction. Spirituality, theosophy and philosophy were central to her out-there vision, and her work reflects that sense of something bigger than us at play – in fact she actually believed her works were painted under the direction of higher spirits. Like others before her, she viewed our existence as only a small element in the larger scheme of things.

Undeniably woo-woo though her vision was, her interest in metaphysics and theosophy was intricate, even semi-scientific, and with its own internal logic – she was drawn to both the spiritualist writings of the founder of the Theosophical Society, Madam Blavatsky, and the philosophical ideas of the Medieval mystic Christian Rosenkreuz. She wanted her work to facilitate spiritual mediation that would transcend physical reality, and to visualise a kind of astral world.

Who knows the precise motivation or meaning behind these extraordinary, liminal, enigmatic artworks? And perhaps that mystery and other-worldliness is what makes the act of looking at them, to some of us at least, such a profoundly peaceful experience.

Harmony of haiku

The traditional form of Japanese poetry, haiku, which consists of 17 syllables in three lines, is widely considered to have a calming effect on the reader. The structure of haiku follows a strict syllable count, and it encourages the poet to focus on a single image or moment, which in itself has a meditative effect. The use of nature imagery in haiku also evokes feelings of serenity and peace. The brevity and simplicity of haiku allows the reader to contemplate and consider the meaning and the imagery without feeling overwhelmed by excessive ideas and language.

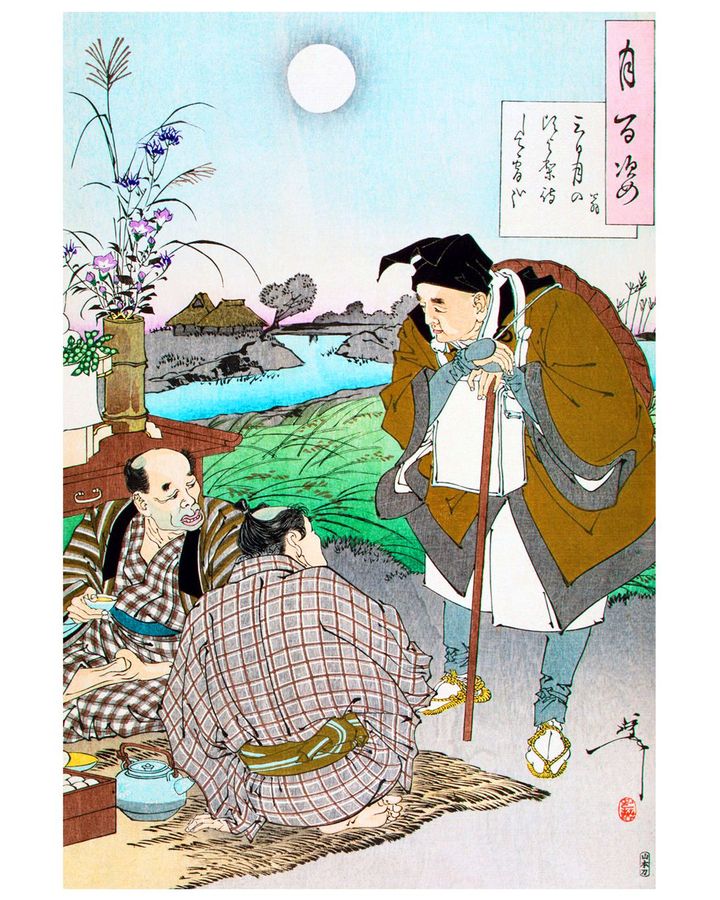

Matsuo Bashō of the Edo period, the best known haiku poet – his complete poetry is translated in the book On Love and Barley: Haiku of Basho – was born in Iga-ueno near Kyoto in 1644, and he began writing verse while acting as a companion to a local aristocrat. Bashō was not only a master of haiku, but also a Buddhist monk and a great traveller – when he travelled he relied entirely on the hospitality of temples and fellow poets.

His gnomic poems combine the Zen idea of a oneness with creation with kurami, or lightness of touch. Each of his poems evokes a scene from the natural world – a leaping frog, a summer moon, cherry blossom, winter snow – which suggest the smallness of human life in the context of the vastness of nature. Pithy and spare, his most famous haiku is The Old Pond: “Old pond/ A frog jumps in –/ The sound of water”. Another is A Leafless Branch: “On a leafless branch/ A crow comes to rest –/ Autumn nightfall”.

Bashō led a solitary life completely free from possessions. Arguably, his haiku are the result of a keen eye and a meditative mind that have been left clear from the distraction of “stuff”, and so he is more alive to the beauty of the world around him – and closer to his own intuition.

The wandering poet Matsuo Bashō was the master of haiku – he renounced all belongings and travelled far and wide, finding inspiration (Credit: Getty Images)

As Daisetz T Suzuki writes in Zen in the Japanese Culture: “A haiku does not express ideas but… puts forward images reflecting intuitions. These images are not figurative representations made use of by the poetic mind, but they directly point to original intuitions, indeed they are intuitions themselves.” The suggestion is that the composition of haiku is so intuitive, it is almost unconscious.

Haiku and their close attention to the details of nature are part of the wider Japanese concepts of nagomi and ikigai, which roughly translated equate to a sense of meaning and harmony. “[Haiku] gives us an insight into why the word ikigai exists in Japanese,” writes Yukari Mitsuhashi in Ikigai: Giving Every Day Meaning and Joy. “In our everyday lives, whether we are immersing ourselves in nature or devouring traditional Japanese food, paying attention to detail grabs our focus on to what is right in front of us, instead of wondering about our to-do lists in our head… permitting us to find joy and ikigai in simple, everyday things.”

And the principles of haiku can be calming when applied to other areas of life, too. In his book Goodbye Things, Funio Sasaki writes: “Traditional paintings have few figures in them and value negative space. Japanese calligraphy and brush paintings are in black and white. Haiku is the shortest poem form in the world. These are a few examples of a minimalistic aesthetic in Japanese art and culture.” In the book, Sasaki, like Bashō all those centuries before, decides to give away most of his possessions, and explores the feeling of calm and tranquillity that results: “There are more things to gain from eliminating excess than you might imagine: time, space, freedom, and energy, for example.”

Find your flow

Calmness is regarded by some with suspicion – is a state of calmness really just a state of passivity? A surrender of engagement, giving up, or, worse, a sociopathic disconnection?

But being calm need not equate with being passive or numb. When we’re absorbed in something we love – music, gardening, drawing, knitting, writing, whatever it is – we can enter an almost trance-like state of calm, mesmerised by what we are doing. As Mitsuhashi argues in her book about ikigai, immersing ourselves in nature or a particular activity makes us focus on what is in front of us, freeing up our minds from other things, and enabling us to find peace.

In her classic work The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron encourages the reader to “make a commitment to quiet time”. She writes: “Creativity occurs in the moment, and in the moment we are timeless”.

And author Mihaly Csiksezentmihalyi argues that what really makes us feel not only calm and peaceful, but also glad to be alive, is unlocking a more fulfilling state of being. He calls this state of mind “flow”. In his book Flow: The Psychology of Happiness, he throws light on the idea that many philosophers before him have posited – that the way to peace doesn’t lie in mindless detachment, but in mindful challenge. Each of us finds our flow in different ways, and our sense of calm.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.