The nation that is the ‘land of song’

Sir Bryn Terfel is pondering a question: what is it about Wales and the Welsh that produces a nation of singers? “I think it’s the mountains, and the fresh sea air. And the language – that is very important,” he says. “Then there’s the hymns… You know, we just love to sing – it’s the air that we breathe.”

More like this:

– Eight of the most stunning opera houses

– The extraordinary ‘lost’ opera composer

– Gen Z and millennials’ surprising obsession

The Welsh bass-baritone is the subject of Peak Performance, part of the BBC documentary series Take Me to the Opera. Presented by Zeinab Badawi, it follows Sir Bryn – as he has been known since his knighthood in 2017 – from his operatic debut with the Welsh National Opera in 1990, to singing at opera houses across the world, like London’s Royal Opera House, where he is a regular star performer. En route, the documentary revisits his roots in rural Wales and looks at how he’s nurturing the next generations of singing talent, as well as his invitation to sing at King Charles’s coronation.

Welsh bass-baritone Sir Bryn Terfel sang at the coronation of King Charles III (Credit: Getty Images)

Sir Bryn is high on the list of great living Welsh opera singers, which also includes luminaries such as Dame Gwyneth Jones, Wynne Evans, Katherine Jenkins, and Aled Jones. (Added to which there are many popular non-opera Welsh singers, including Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey, Bonnie Tyler, Charlotte Church and Cerys Matthews.) But beyond these headline stars lies a whole nation renowned for its love of singing, especially choral. So where does this passion for song stem from?

In A History of Music and Singing in Wales, novelist and poet Wyn Griffith, who wrote extensively on Wales and Welsh culture, observed: “If you find a score of Welsh people, in Wales or out of it, you will find a choir. They sing for their own delight, and they always sing in harmony. They sing as naturally and easily as they talk.”

“Wales is known as a nation of music – the ‘land of song’,” notes the Welsh National Opera (WNO). “Often connected with male voice choirs, it is… recognised for its choral traditions which are rooted in the culture.”

Choral singing in Wales dates back to the 19th Century, and flourished with the Cymanafa Ganu (hymn singing) movement, at a chapel in Aberdare in 1859; it was rooted mainly in religious songs, though a steady body of secular songs were also produced. Soon after, a revival of traditional Welsh music began with the formation of the National Eisteddfod Society, a focus for the Welsh passion for singing and song. Any worthy list of classic Welsh songs might include Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau (O Land of My Fathers); My Little Welsh Home by William Sidney Gwynn Williams; and the love song Ar Lan y Mor (recorded by both Terfel and Jenkins). Or the rousing We’ll Keep a Welcome (In the Hillsides).

The male voice choir, along with the harp, are two of the most popular signifiers of Welsh music. Professor Gareth Williams traces the male voice choir’s origins to the mid-19th Century industrial age: “We are reminded of what Aneurin Bevan once said: ‘Culture comes off the end of a pick’,” he writes, referring to Welsh coal miners. Choirs started in the 1920s, like Cwbach from the Cynon Valley, and Pendyrus, survive today. After a day’s hard graft in a mine, says Williams, the joy and community found in singing with co-workers was “an assertion of working-class male bonding and identity expressed through that most democratic and inexpensive instrument, the human voice”.

The Welsh Borough Chapel in Southwark, London, is host to Eschoir, a Welsh male choir of around 20 singers, aged 20 to 75. Singing together since 2009, they’ve performed at Buckingham Palace, 10 Downing Street, and the Six Nations rugby tournament. Eschoir founder and director Mike Williams, who grew up in south Wales, describes their appeal: “There’s a humility to it, as Welsh choirs stem back to the coal mines and chapels. Many people enjoy singing in the pub as much as singing in a concert. There is no pomp… it unites us and keeps us connected to our Welsh roots.” And the Welsh take choirs very seriously, he adds.

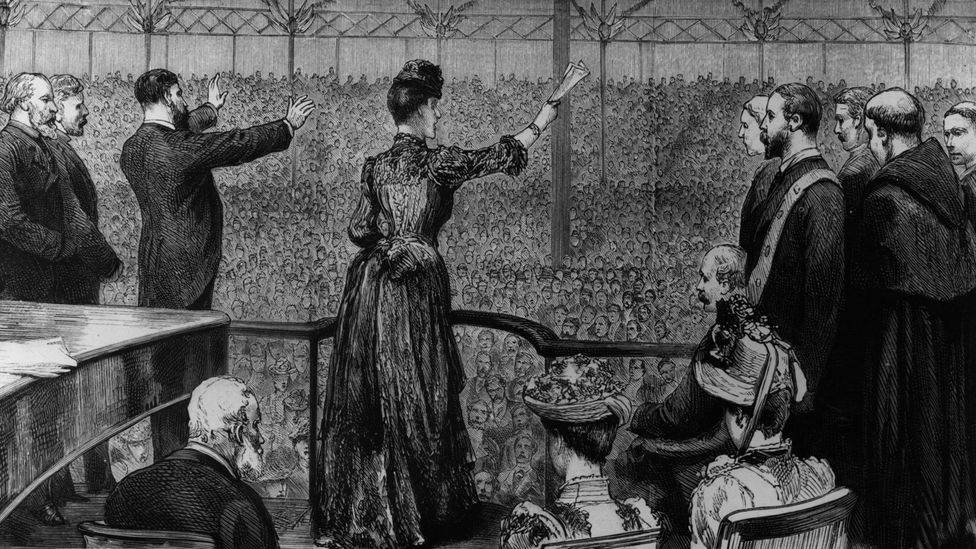

Opera singer Adelina Patti joins in the singing of O Land of My Fathers at the Royal National Eisteddfod, 1889 (Credit: Getty Images)

In tandem with a passion for choral singing in Wales, there has been a rise in popularity of the Eisteddfod. These Welsh singing and recital competitions date back to the 12th Century and today are a platform for public singing, especially for younger singers. It was at local Eisteddfods that the young Bryn Terfel first stood out, winning singing competitions that would lead him to study at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and to his first professional role in Cosi Fan Tutti at Welsh National Opera, soon after graduating in 1989.

A unique cultural inheritance

In the documentary, Terfel recalls competing in Eisteddfods in his rural north Wales, and how his “parents paid for a lot of petrol to drive me north, south, east and west to compete. They saw something in their son… the passion, how I loved singing. I think that drove them to encourage the singing within me.” Eisteddfods are “a wonderful shop window”, he says. One of his charitable initiatives is a scholarship to develop promising young performers coming up through Eisteddfods. Peak Performance visits one in Llanadog, near Swansea, as young singers of all genders, from the area and across Wales, prepare to get on stage and sing. “This is where it all starts for us Welsh singers,” says one teenage boy in the documentary. “This is where we learn our craft.” He believes when Welsh singers go to London to study, “you can see the difference… they’ve got some sort of… confidence.”

Certainly, Terfel was swaddled in song and music from the cradle. Born in 1967 in rural north Wales, his father was a farmer, his mother a special needs teacher who used music therapy in her work. The whole family, including older relatives, sang together and in choirs. “My grandfather, my great-grandfather, had the love of singing,” he says. “There was constant learning going on in the kitchen, words on the cabinets. A little bit of rivalry as well, which is quite healthy.”

Eilir Owen Griffiths, a composer and Eisteddfod adjudicator, explains what he looks for in a great singer: “It’s how the voice resonates, and the way it works with text.” He describes Terfil’s voice as “like a beautiful double bass” – but it’s not just the incredible sound he generates: “It’s also the control he has – he can sing the most delicate pianissimo as well. It’s a unique voice, very special.” That quality – and cultural diversity – was drawn on when Sir Bryn sang at the coronation of King Charles, who personally chose him to perform; he sang Coronation Kyrie, a first in the Welsh language at a coronation. “You have the rehearsals in the rooms… Then you have your fittings, and all of a sudden you’re in your costume and make-up.” And you’re onstage, he says, “portraying a character. And that’s when the fun really does begin!”

A harp sculpture stands outside the International Musical Eisteddfod site in Llangollen, Wales (Credit: Alamy)

The documentary joins Terfel as he goes through his repertoire for a week in March: as well as the Barber of Seville at the Royal Opera House, he sings the title role in Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi at the Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool; then travels to a studio near Cardiff in Wales, to record an album of sea shanties – the likes of Drunken Sailor, and traditional folk songs like Fflat Huw Puw, “about a sailor and his wonderful ship”.

It’s a voice that continues to thrill audiences, whether in lead roles such as Mozart’s Don Giovanni at the Royal Opera House; or Tosca by Puccini at Paris Opera Bastille; or Verdi’s Falstaff, at Grange Park Opera, Surrey. As well as big opera houses, he performs for new audiences in concert halls too. Gillian Moore is artistic director of the South Bank Centre, where in recent months he sang extracts from two of Wagner’s great roles: “The fact he’s passing that on to young singers makes total sense… When he’s on stage, you cannot take your eyes off him.”

Returning to that question of why the Welsh love to sing, Wyn Griffith suggests it’s about an irrepressible spirit – and it’s simply in the blood: “Whether they meet in tens or in thousands, in a small country chapel or in a vast assembly… they sing freely… It is not necessary to organise singing in Wales: it happens on its own.”

Take me to the Opera: Peak Performance is on BBC News Channel on 10 June at 13.30 and also on BBC Reel

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.