The woman whose naked body was a canvas

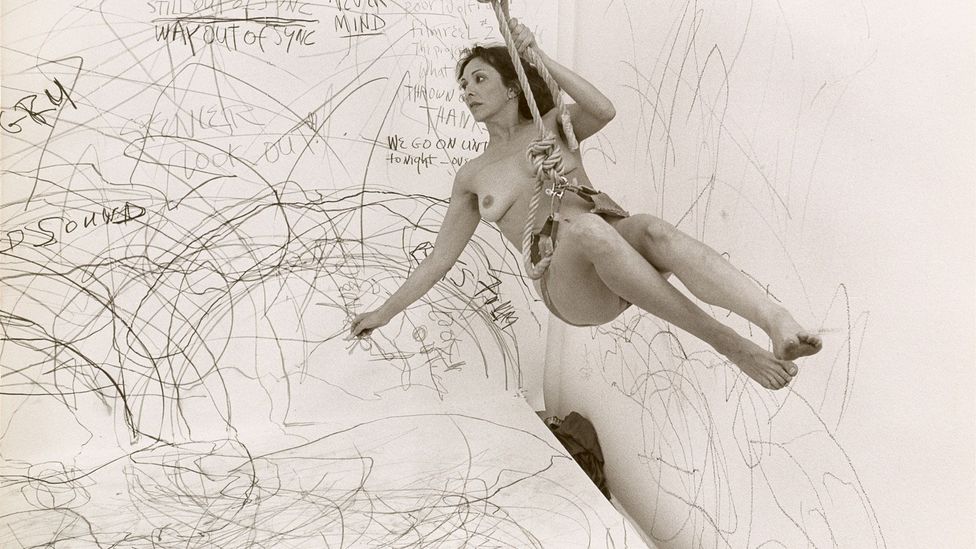

In 1977, the US artist Carolee Schneemann was invited by the Telluride Film Festival to introduce a programme of films directed by women, including her own Fuses (1964-7) and Plumb Line (1968-71). When she arrived, Schneemann saw that the series had been given a title, The Erotic Woman. Incensed at the suggestion that these films were displays of female eroticism for the pleasure of others, presumably men, Schneemann abandoned her prepared introduction and instead read a scroll pulled from her vagina. The scroll’s text comes from her film Kitch’s Last Meal (1973-6), a Super 8 film of her cat with the narration played on an unsynced cassette. It is a letter addressed to a fictional “structuralist filmmaker” who attacks her “persistence of feelings” and “diaristic indulgence” of the self.

Warning: this article contains nudity

More like this:

– The artist who likes to blow things up

– How vaginas are losing their stigma

– The new female rage in film and TV

The performance, named Interior Scroll, reclaims the centering of Schneemann’s own body in her art. She first performed the work in East Hampton, New York, in August 1975, in a planned manner as part of an exhibition entitled Women Here and Now. The restaging at Telluride gave the work a whole new resonance: this time, the performance was spontaneous and impulsive, using the physical act of the work to reframe the apparent “eroticism” of the films Schneemann had curated.

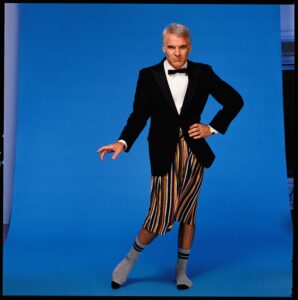

Schneemann’s film Fuses reflects her desire to celebrate her sexual agency in her work (Credit: Carolee Schneemann Foundation / ARS, New York/ DACS, London)

Describing this event, this happening, this performance can never do justice to the power of the moment itself. We can gain an impression of what it was like, we can look at the scroll behind glass, we can see photographs of Schneemann reading it, crouched and naked before her audience. But we cannot really know how her audience at Telluride felt when they saw and heard it happening before them, or feel the rage pulsating through Schneemann as she recreated the work on stage. Reflecting on her 1963 work Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, she once wrote that “I wanted my actual body to be combined with the work as an integral material.” How then can her performance art be displayed when the body itself is not present?

This is a question answered in a myriad of ways by Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics, the first major retrospective of Schneemann’s works in the UK at the Barbican in London. Schneemann died in 2019, and there is a specific challenge of bringing historical performance art to a retrospective exhibition. The show does this through a plethora of display techniques, combining projected films, still photography, archival writings such as performance instructions, and tactile objects including costumes and props. Curator Lotte Johnson tells BBC Culture that, “Schneemann herself was sensitively attuned to the condition of performance as an ephemeral, time-based form of expression.”

This is why Schneemann’s archive is full of hundreds of photographs, slides, negatives and contact sheets which together offer as close to a three-dimensional realisation of what took place in the moment of the performance itself as possible. Johnson further reflects, “These photographs and moving image documentations, which Schneemann often edited into her own incredible film collages, have been absolutely crucial to the challenge of bringing her work back to life through our exhibition.”

Schneemann’s art spans six decades from the late 1950s, refusing to fit into any clear categories of period or genre. She grew up in 1930s Pennsylvania before studying at Bard College in New York state, from which she was expelled in 1954 after two years for “moral turpitude”, due to painting her own nude body when Bard refused to provide her with life models. In doing so, Schneemann connected with herself artistically in a way that defined her work thereafter. She moved to New York, a city caught in the throes of Abstract Expressionism and an art world full of men, whom she dubbed the “Art Stud Club”. Where men took inspiration from women’s bodies, Schneemann had the self-possession to put her body into the work directly. She took herself off the canvas to create from the body itself, developing a mode of art alongside her peer Yoko Ono which inspired subsequent performance artists including Marina Abramović.

A gesture of liberation

The taboo of the female body as a sexual agent in and for itself lies at the core of Schneemann’s work. That is, that a woman is not simply an object of male desire in society and in the sex act itself, but rather a subject who can and should feel pleasure. The societal gaslighting performed by patriarchy, specifically of men convincing women that their own pleasure is the focus of intercourse, with the male orgasm as telos, had in Schneemann’s view forced women into submission. Johnson reflects that, “For Schneemann, working with and from the body was a gesture of liberation.”

By being liberated, women are able to reclaim their own pleasure and the equal importance of their orgasms to that of their male sexual partners – to not see sex as an act of servitude, but one that might serve their own desire. It was out of this purpose that Schneemann’s great work Meat Joy emerged: first performed in Paris in 1964, and then made into a film based on footage from a number of performances that year, it featured men and women tangling together in a mess of feathers, raw meat, shredded paper, and paint. Schneemann called Meat Joy an “erotic rite” that led to “flesh jubilation”, a return to a primitive, quasi-pagan form of bodily movement that deconstructs the “masculinist culture” which has developed in capitalist society. The work is furious, with the artist blending her own body into the mass of nude figures on the stage as they tear at each other to remove sexual difference in the final collation of flesh.

Meat Joy stands in contrast to Schneemann’s more personal film Fuses, shot between 1964 and 1967 with her partner of 13 years, the composer James Tenney. Here Schneemann uses 30-second shots from a wind-up, 16mm Bolex camera to show their sex from her own perspective, positioning the camera from every conceivable angle in their home. Schneemann described the film as revealing the “lived sense of equity” between the couple, of shared pleasure and the paying of attention both to the self and each other.

Schneemann performed Interior Scroll twice – first in a planned, then spontaneous fashion (Credit: Carolee Schneemann Foundation / ARS, New York/ DACS, London/Anthony McCall)

Schneemann also brought the vulva and specifically the clitoris into the frame in order to counter the historical phallocentrism of sex. Her 1995 multimedia work Vulva’s Morphia came from a dream in which she heard the question, “Why don’t you let the vulva do the talking?” Schneemann created a grid with various yonic figures, real and illustrated, and annotated them with text imagining the vulva as its own being in active rebellion, fighting back against those who seek to undermine its independent function, desire, and pleasure apart from the penis. It is an act of aggression against the misogynistic theorisations of sexual difference by writers like French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who see women’s genitals as an object in relation to a male subject.

The question is: when does the body stop being a body and become an artistic medium? Johnson says that, in Schneemann’s work, the body always remains a body. “This is integral to the feminist politics that runs through her myriad forms of expression. For Schneemann, life and work were intimately intertwined; just like in life, in Schneemann’s work bodies are precarious in all their eroticism, joy, rage, ecstasy, pain and suffering. Writing to a friend in 1976, Schneemann explained: ‘I do not ‘show’ my naked body! I am being my body.’ She took her body’s sensory experience as a starting point for her work, understanding herself as inextricably linked with her environment and the bodies of others.”

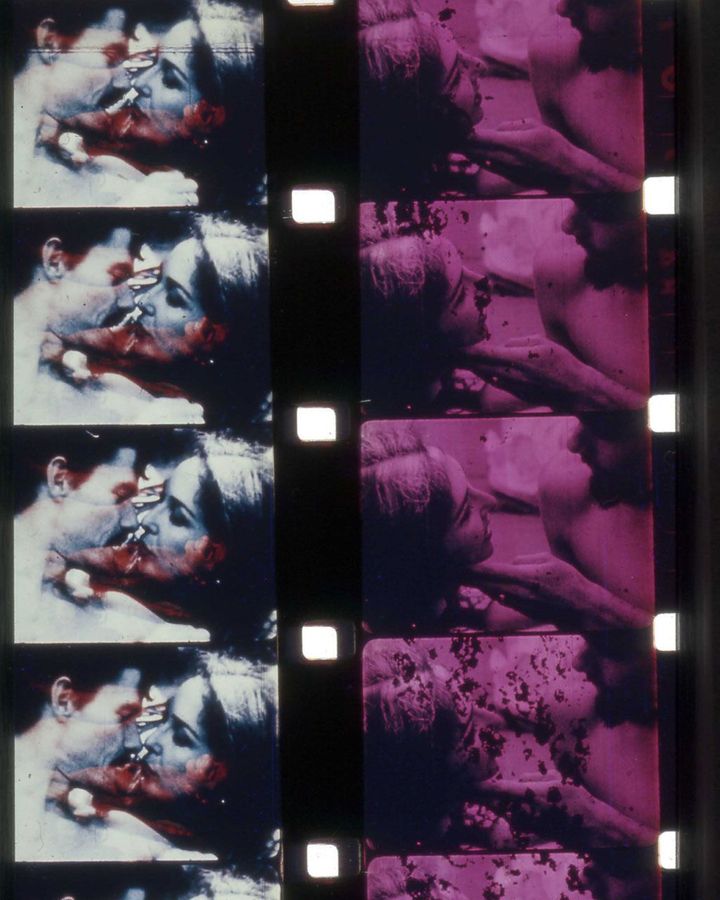

One of Schneemann’s first performance pieces displayed in the Barbican retrospective is Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera. The wall is covered in a grid of photographic prints showing a naked Schneemann in her own studio surrounded by paintings she was in the process of making at the time. Here she interrogates the distinction between being an image and being the maker of that image, to discover where the lines of overlap exist so they can be exploited and broken down. Schneemann’s fine art begins to blur with her performance, as she moves paint from the traditional canvas to her own skin, and by interacting with those static works, she becomes a living part of them. Asked about the various mediums displayed in the Barbican’s retrospective, Johnson says that, “Schneemann didn’t see boundaries between ‘fine art’ and ‘performance’, rejecting these restrictive categories.”

In Eye Body and many of her later works, Schneemann performs alone. She equips herself with the tools of performance and orchestrates the work herself before the audience. In this way Schneemann’s art differs from her contemporaries, such as Ono, who in her 1965 performance of Cut Piece at Carnegie Hall invited audience members to approach her with a pair of scissors and cut her clothing. While most braved only a single snip, it was not long before a man delighted in seeing the fabric fall away, cutting through Ono’s bra straps to reveal her naked breasts. Schneemann’s nudity is firmly an act of choice, of self-liberation, while in that piece, Ono’s is enacted by the viewer.

Similarly, Serbian artist Abramović has throughout her career set up her performances to test the actions of her audience, most terrifyingly in her work Rhythm 0 performed at Naples’ Galleria Studio Morra in 1974. Standing still for six hours, Abramović laid out 72 objects on a table ranging from a rose and a feather to a knife and a gun, which attendees could use on her body in any way they liked. The piece escalated from her clothes being cut off like Ono a decade earlier, to having her body harmed in various ways until one man held the loaded gun to Abramović’s head and tried to make her fire it before other members stopped him.

These performances by Ono and Abramović use the body as a stage rather than as a canvas, on to which others are invited to be performative. Those women allowed others to create the art themselves, highlighting the potential of others to do harm to that which is perceived to be beautiful. By contrast, Schneemann made art with her own body – the beauty is not objective but subjective, one which she remains in control of. The intent of Schneemann’s art is different to Ono or Abramović, seeking not to display the cruelty of men for its own sake but rather to do so by celebrating and liberating the female body simultaneously.

Acting as her own muse

Schneemann’s work also observes the artistic tradition of male artist/female muse and subverts it by making muse and artist one and the same. Consider an early example of male-created performance art in the 1960s, Yves Klein’s Anthropometries, in which he stood in a suit and instructed naked women to roll around on sheets of paper covered in blue paint to the sound of a string quartet. In response to this imbalanced dynamic, Ono in Cut Piece and Abramović in Rhythm 0 removed the singular male artist to leave open their female bodies to the risk of a live audience. Schneemann went a step further in her work, removing the participative aspect of the viewer to give herself total agency before them, working as female artist/female muse to act in and for herself.

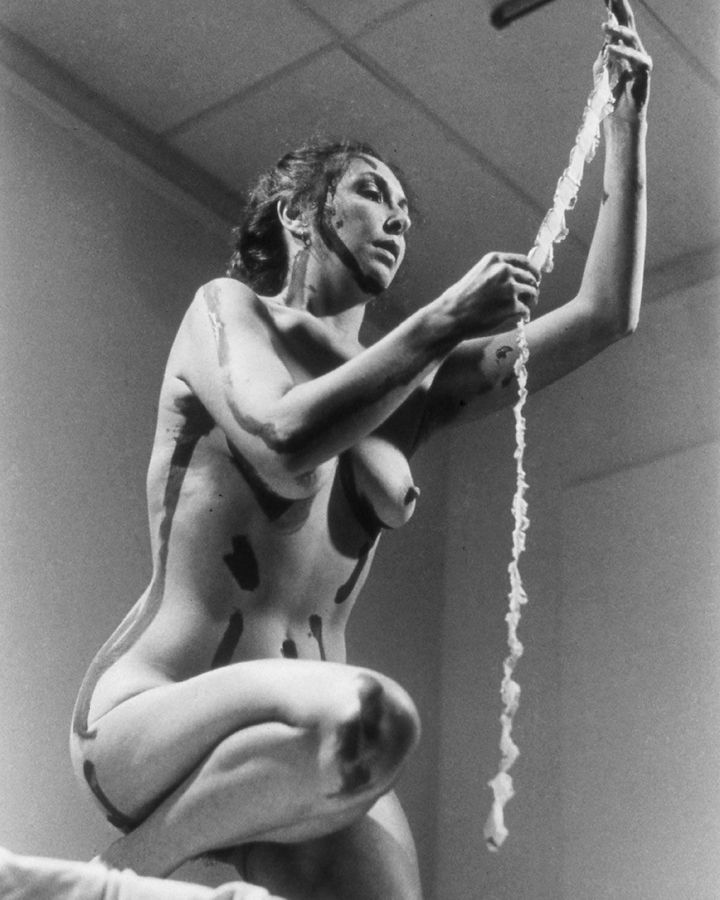

In Up to and Including Her Limits, Schneemann swung between walls of paper making marks with crayons (Credit: Carolee Schneemann Foundation / ARS, New York/ DACS, London)

Take for example one of Schneemann’s “action paintings” – a term coined by critic Harold Rosenberg in reference to Jackson Pollock’s physicalised artistic process – Up to and Including Her Limits, performed in 1976. The artist suspended herself from the ceiling by a rope harness between walls of paper, then with crayons in her hands she swung between them and made marks. Schneemann invites her audience to watch her in media res, displaying the process of creation as the artistic end in itself. In other words, what is left on the paper at the end of the performance is not the art – it is her body suspended and in motion, beholden to her own self-imposed restrictions through the placement of the harness. Everyone has limits of freedom; here, she can only create so far as the restrictions on her creativity allow. The visualisation of that invisible internal and external experience is the essence of the piece.

In the Barbican exhibition, Up to and Including Her Limits is displayed with the suspended rope harness between the walls of paper, with photographs and video nearby to illustrate the original performance. Yet there is a remove created by seeing the space without Schneemann in it herself, an acknowledgement of the curator’s own limits on how far the act of performance can be restaged. The Barbican’s various methods of display in the exhibition opens questions for other ways in which performance art can be brought back into a new gallery space.

In September 2023, London’s Royal Academy of Arts will open an Abramović retrospective, promising “live re-performances” of the artist’s works. But with a different audience, a different placement in time, a different body, it remains to be seen how much of their original essence can be retained. What impact can really be felt when an audience knows that someone will take the gun from the table with no intention of firing it? The Barbican exhibition does not attempt to recreate Schneemann’s performance art. It memorialises the artist and her works while acknowledging the role of ephemerality in their conception. Without Schneemann herself present, the audience becomes responsible for projecting the body back into the art.

Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics is at the Barbican, London until 8 January 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.