Unflinching images resisting injustice

In 2009, a government minister in Johannesburg walked out of an exhibition in protest after seeing photographs of nude lesbian couples. Despite South Africa being one of the first countries in the world to prohibit discrimination against same-sex partners in 1996, and gay marriage being legalised three years before the incident, the minister’s controversial exit was seen by many people as a testament to how far the country still needed to go to reach equality. The show, titled Innovative Women, featured photographs by the non-binary activist Zanele Muholi, now one of the most acclaimed photographers working today.

Warning: This article contains distressing details about hate crime

More like this:

– The 80s artists who predicted the future

– The portraits that question history

– The century’s ‘most important painting’

Born in 1972 in Umlazi, a township in South Africa, Muholi, who uses the pronouns they/them, has been documenting the experiences of the black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa for two decades. Over the past two years, more than 250 of these works have been exhibited in a travelling retrospective across Europe, including at the Tate Modern in London, and in Berlin, Denmark and Reykjavik. It is now showing at Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), a centre for contemporary photography in Paris, until May. “Muholi is not just somebody who makes incredible images, but they are also an incredible activist, speaker and advocate,” says the director of the MEP Simon Baker. “Paris needs Muholi more than Muholi needs to be in Paris.”

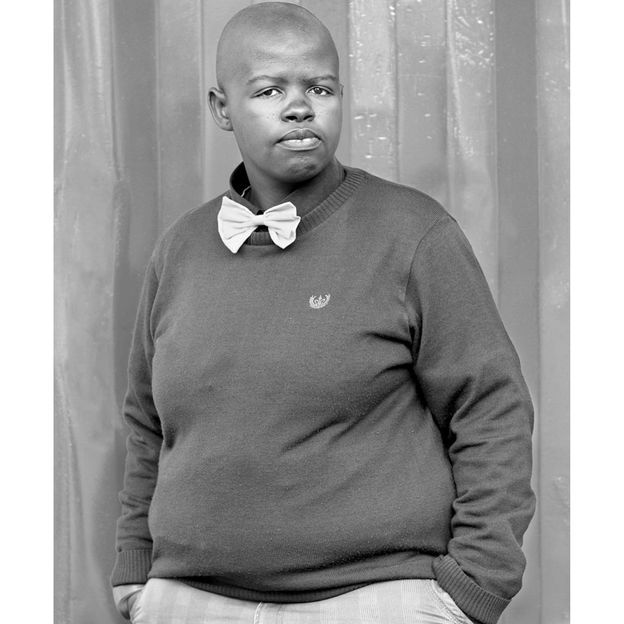

From the Faces and Phases series, Lungile Cleo Dladla, KwaThema Community Hall, Springs, Johannesburg (2011) (Credit: Zanele Muholi/ Stevenson/ Yancey Richardson)

Muholi refers to themself as a “visual activist” rather than as an artist, which they believe better describes their practice. According to Muholi, working with visual mediums allows their work to be accessible to a range of people. It ensures “that those who might not be able to read or write, or do not have an understanding of the [language] attached to queerness” can digest their message, they tell BBC Culture via video call, dressed in a green jumper and wide-brimmed hat with a cut-out on top to make room for their long hair. Their work is “pushing a political agenda, using the visuals as means of articulation,” they add.

Part of Muholi’s lexical choice for describing their work is rooted in how they have approached their artistic career. The activist was raised by a single mother under apartheid, the system of racial segregation in South Africa put in place under an all-white government from 1948 to 1994. They initially turned to image-making as a process of self-healing, studying advanced photography at Market Photo Workshop, a photography school in Johannesburg, in the early 2000s. They also co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women (FEW), a black lesbian rights organisation, and later gained an MFA in documentary media in 2009.

A core part of Muholi’s oeuvre was and still is about providing visibility for the LGBTQIA+ community that is not entrenched in victimhood. “We are only written about in history when one of us has become violated somehow, which then makes us a spectacle,” they say. “I’m bringing celebration in [to the narrative] and commemorating all those that came before us.” Their approach often means finding the middle ground between highlighting the atrocities of prejudice, and the joy within LGBTQIA+ relationships.

The exhibition at the MEP is a survey of Muholi’s oeuvre – shown here, Aftermath, from the Only Half the Picture series (Credit: Zanele Muholi/ Stevenson/ Yancey Richardson)

For many people in Europe, South Africa is still understood in the context of apartheid. However, this understanding often does not expand into how the system still affects black people in the country today, especially those in queer communities, who are still targets of violence. “People have a residual sense of what apartheid means, but in terms of what those experiences actually are, and the way they’re still playing out, that’s something that people are maybe not so aware of,” says Baker. The first series Muholi produced, titled Only Half the Picture (2003-2006), features photographs that simultaneously document intimate moments of people in the queer community, while also addressing past physical trauma. Aftermath (2004), for example, depicts the lower torso and legs of a person wearing briefs, a large scar visible on their right thigh.

But, for Muholi, their work also provides a space for the queer community to tell their own story, especially in South Africa. “You have museums in almost every European country, but you barely find properly allocated space for black LGBTQIA+ persons,” the photographer and activist says. London’s Tate Modern held a retrospective of Muholi’s work in 2020-21 – among the essays in the exhibition catalogue is a testimony titled I am not a Victim but a Victor, written by Lungile Dladla, a South African lesbian. Dladla recounts an evening in 2010 when a man sexually assaulted her and her friend at gunpoint on their way home from her aunt’s funeral, calling it “corrective rape”: “He said, ‘Today ngizoni khipha ubutabane.’ (‘Today I will rid you of this gayness.’),” Dladla wrote. One of the series Muholi has become known for, titled Faces and Phases, includes a photograph of Dladla from 2006, dressed in a sweatshirt and bowtie.

Brave beauties

Faces and Phases is an ongoing collection of more than 500 black-and-white portraits of black lesbians and transgender people, depicted by Muholi in the ways the individuals themselves wish to be seen. In each image, the person looks straight at the camera, seemingly demanding the viewer to look at them properly. “Muholi is invested in making sure that the person being photographed feels and is genuinely in control of the way they’re being shown,” says Baker, noting that some of the people pictured also have recorded testimonials in the exhibition. “It’s always a process of discussion, an understanding between Muholi and the person they’re photographing.”

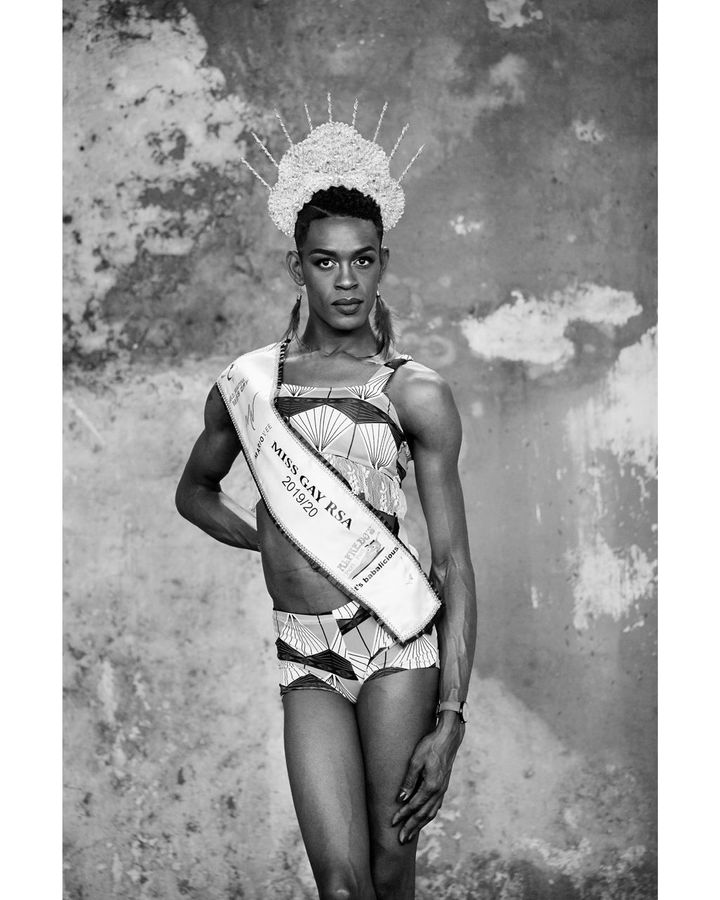

The more recent series Brave Beauties highlights individuals who have shown courage in the face of prejudice – pictured is Candice Nkosi, Durban (2020) (Credit: Zanele Muholi)

Muholi calls each person featured in Faces and Phases a “participant”, highlighting the collaborative approach to image-making in the series. “In the photo world, those who are photographed are called sitters, models or subjects. There is already that hierarchy that places the photographer on top, and those being photographed are perceived as subordinates,” Muholi says. “I choose to break these hierarchies. There is no subject because the people being photographed are the kings and queens who define what we do. They are the ones who are supposed to be on top of the pedestal because, without them, there are no photographs.”

Nakamori, who is also the senior curator of international art (photography) at Tate Modern, says Muholi is challenging traditional approaches to the representation of black people in the history of photography. “In early-mid to late 19th-Century material, black bodies appear in the ethnographical context, and none of them were given their names. Often they were just seen as objects of curiosity,” he says. “Muholi critiques that by looking at select individuals fully, giving everyone their own names [as the title of the image].”

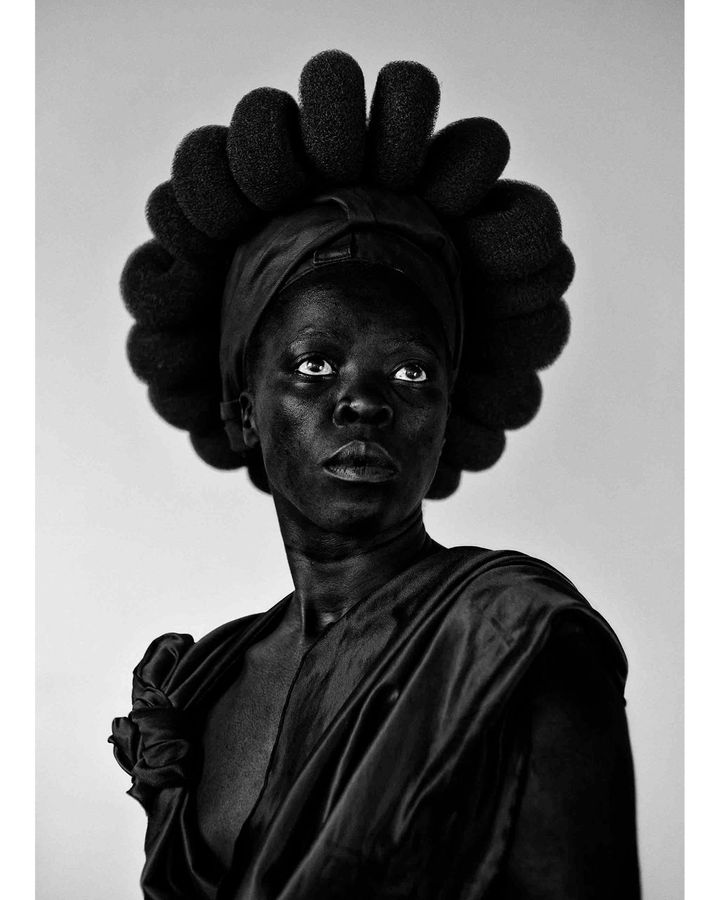

Another way Muholi questions representation is through their ongoing self-portrait series Somnyama Ngonyama (or Hail the Dark Lioness in English), which they started in 2012, where they depict themselves in multiple guises. In Ntozakhe II, Parktown (2016), Muholi wears a toga-like outfit with a crown of round scouring pads, seemingly in place of their hair. Unlike Faces and Phases, the images in Somnyama Ngonyama are also heavily edited to darken Muholi’s skin in order to accentuate their blackness. In Thulani II, Parktown, 2015, Muholi is dressed as a South African miner in a helmet and goggles to commemorate the Marikana massacre in South Africa in 2012. “For those who don’t know, the Marikana Massacre saw 112 men shot down, killing 34 as they walked out on strike at a platinum minefield in South Africa,” Muholi told Dazed Digital in 2017. “I’m speaking about minimum wage, displacement, but most importantly, the unexpected deaths of so many.”

Ntozakhe ll, Parktown (2016) from the series Somnyama Ngonyama, in which Muholi depicts themself in various different guises (Credit: Zanele Muholi)

As Muholi’s most popular series show, their work is rarely designed to be seen as singular photographs but as collections. “Muholi’s work essentially serves as an archive,” says Nakamori. “Archives have to have multiple images so that people, particularly those who come afterwards, can study the people who are photographed.” A goal for Muholi is that one day, there will be a space for creations of and by LGBTQIA+ black people in their homeland. “It’s about time that we have a museum in Africa that is dedicated to queer and trans lives because, for too long, we have been contributors, but representation is less,” says the photographer. “It is that absence that I want to undo.”

Zanele Muholi is at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, until 21 May 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.