What defines cultural appropriation?

In 2019, a major Italian fashion house launched a collection of maxi dresses and skirts in cotton poplin, broadly edged with contrasting ethnic prints of distinctive swirls and star shapes. Only if you’d visited the small Oma communities in northern Laos, would you have noticed that the designs were simply digital prints of the tribe’s traditional clothing: handspun, indigo-dyed garments with vibrant appliqué and embroidery. Lauren Ellis, at the time an employee of Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre, had. “They had copied the patterns exactly,” she told the Laotian Times. “I couldn’t believe that this major brand would sell such blatantly stolen designs.”

More like this:

– The revival of ancient beauty rituals

– How to make your clothes last longer

– Inside the ethical beauty boom

Working with the Oma, the centre launched a campaign highlighting the situation. “The handmade textiles of the Oma are incredibly detailed, taking a huge amount of time, skill, and patience,” said co-director Tara Gujadhur. “To see them reduced to a printed pattern on a mass-produced garment is heart-breaking.” Dr Marie-Pierre Lissoir, the centre’s ethnomusicologist and researcher, added: “Communities and their traditions are in constant change. They adapt themselves and get inspired by other cultures.” However, this was not a case of a brand being inspired by motifs, and reinterpreting them, she says. “They simply scanned a handmade piece and printed it on clothes without even mentioning the existence of Oma community. This is not cultural appreciation. This is not creative interpretation.”

The Akha Oma of Phongsali province, Laos, create exquisite traditional dresses and headdresses (Credit: Getty Images)

The fashion industry is no stranger to such controversies. Just the year before, D&G’s tone-deaf campaign showing a Chinese model attempting to eat pizza with chopsticks led to an eruption of fury on China’s social media platform Weibo, and a public apology from the designers. Pre-pandemic, pre-Black Lives Matter, the fashion house Comme des Garçons was taken to task after white models wore wigs of what appeared to be cornrows during its men’s autumn/winter 2020 show. And of course, there is the ongoing trend at music festivals for tribal accoutrements, including Native American headdresses, in an attempt to ape the mystic of indigenous tribes, if only for a weekend.

Why does our concern about cultural appropriation matter? Designers and artists have been drawing inspiration from each other for millennia. Cut off that blood supply of creative exchange and communities would be left, not only with a smaller palette of ideas but far narrower views of the world and the other ways of being on it. Plus, the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation can be thin; after all, why copy something if you don’t love it?

However, for many cultural commentators, the nature of the relationship continues to be problematic. Tamsin Blanchard is curator of Fashion Open Studio, an initiative by campaign group Fashion Revolution showcasing the work of ethical designers. This year, working with Not Enough, a collective of South American women looking at how art and design have worked to perpetuate colonialism, Fashion Open Studio is co-curator of the prestigious State of Fashion Biennial in Arnheim. “Traditionally, designers were taught at fashion schools to pick and mix from the world around them, be that from an art exhibition, film, the natural world, or the culture and heritage of global communities,” reflects Blanchard.

“We’re all drawn to an exquisite piece of embroidery, a colourful textile or even a style of dressing that might have originated from another heritage. [But] this magpie mentality, where all of culture and history is up for grabs as ‘inspiration’, has accelerated since the proliferation of social media,” she continues. “Where once a fashion student might research the history and traditions of a particular item of clothing with care and respect, we now have a world where images are lifted from image libraries without a care for their cultural significance. It’s easier than ever to steal a motif or a craft technique and transfer it on to a piece of clothing that is either mass produced or appears on a runway without credit or compensation to their original communities.”

Knowledge matters. How many white people wearing cornrows (hello, Kim Kardashian and Katy Perry) know that, in 15th-Century Africa, hair was a way to distinguish a person’s age, religion, social rank and marital status; that braiding took hours, even days, to complete, and were times of great bonding; or that, during the slave trade, heads were shaved, tearing from the African peoples not only their hair, but also their identities? How many festivalgoers are aware that Native American headdresses are made from eagle feathers, symbolic of the Great Spirit, only gifted to wearers when they have done something of note for the community? How many know that the bindi, another festival favourite, is thought to enhance the powers of the third eye, by facilitating one’s ability to access their inner wisdom or gurus.

Blending influences, but not appropriating, the brand Aciela draws on its Colombian heritage and folklore, along with traditional British tailoring (Credit: Aciela)

And how many would have known that in the past – and even now – the originators of the cornrows, the headdresses, the bindis, would have been persecuted for wearing them? In a 2018 BBC Stories documentary Cultural Appropriation: Whose Problem is it?, interviewee Ayesha says: “When you are part of a society that has told you how you look is wrong, for someone in that society to then say, ‘well, I’m going to do it because it’s fashionable, and it’s a music festival so who cares’, is very ignorant to the people who have had to go through those things.” Interviewee Karisha adds: “When one racial group in their history has taken from a different racial group, and then in the future, wears the same things, it’s like a slap in the face.”

Cultural anthropologist Sandra Niessen has researched Indonesian Batak weaving for more than 40 years. In 2020, she wrote a paper called Fashion, its Sacrifice Zones and Sustainability. Inspired by the concept of the “sacrifice zone”, Niessen dug deep into the colonial underpinnings of the industry, going far beyond whether black models were included in a catwalk show to an exploration of the way the traditions of the indigenous peoples have been simultaneously plundered and erased. “Sacrifice zones are resource-rich lands, generally associated with minority communities that are considered dispensable, and exploited for economic gain,” Niessen explained in the paper.

“Rather than expendable physical landscapes, fashion sacrifice zones are dress traditions, and their makers, associated with fashion’s ‘other half’, that are destroyed for, and by, the expansion of industrial fashion. These zones facilitate industrial expansion because they are a source of cheap labour and also indigenous design (commonly appropriated) important for style change.” This catalogue of injustices continues: “[These sacrifice zones] also serve as markets when indigenous dress is replaced with industrially produced dress. Finally, they are the major sites of waste disposal, including second-hand clothing.” The paper is a searing critique of fashion’s wilful systems of inequity, and remains seminal to those seeking to address cultural imbalances.

“All peoples everywhere derive inspiration from elsewhere,” says Niessen, by email from her home in the Netherlands. “The problem is the hierarchy, with designers at the top and indigenous clothing at the bottom, to be pillaged from but not acknowledged. The system is skewed, not the creative work of designers per se. To recruit indigenous people to make luxury fashion acknowledges their skills but not their right to their own clothing systems. And to reduce their clothing systems to design and skill is to do it a fundamental disservice; it’s a form of erasure. Working within the fashion system is the problem, not the exciting process of cultural contact.”

Textiles designer Ellen Rock works in close collaboration with artisans in Nepal, exchanging ideas and skills (Credit: Ellen Rock)

What would she like to see? “The fashion business supporting the needs and desires of indigenous dress makers and not the other way around,” she says. “To place ‘them’ first would be a restitution, perhaps revival, of ‘their’ systems. It’s time to ask what fashion can do for them, not what they can do for fashion. They need the chance to be able to live their own cultural lives. They need their lands revitalised, their systems respected, self-determination. They need clean air and clean water. Our debt to their health and their way of life can’t even begin to be tallied up.”

The issues of respect and of concern for other cultures – of which Niessen’s paper is such a nuanced expression – has become more marked in a world still battling a global pandemic, jolted awake by Black Lives Matter, and damaged beyond recognition by global warming, itself directly caused by consumption. Within this context, many are questioning whether the extractive model of infinite growth, born from a history of colonial exploitation, is all it’s cut out to be; whether it may, in all that matters, actually be one of the worst ways of moving forward. Attention is turning, with a renewed humility, to indigenous practices, tried and tested for millennia, for stewarding the Earth.

And it is turning to what other practices – of organising communities, of exchanging skills and of making clothing – may have to offer as alternatives to the hyper-industrial, hegemonic Western fashion industry. “The Black Lives Matter [movement has led to a] mass realignment and re-education, and an understanding of how our colonial past and empire-building was built on the exploitation of people and theft of indigenous land and resources,” says Blanchard. “There’s a new awareness of cultural imbalances and the inequalities within the fashion industry, where a thousand-pound dress has been made by garment workers who are not paid a living wage, or where a motif has been taken from a community’s cultural textile heritage without permission.”

A shared vision

Increasingly, the industry is asking itself: what are the new systems that can take us into the future? And what are the ways of working across cultures that ensure that each party is adequately represented and recognised? “For cultural collaboration to exist, a shared vision needs to be established,” muses Kerry Bannigan, executive director of the Fashion Impact Fund. “Collaborative collective leadership is necessary along with assessment of all processes in the project. Designers and brands need to understand that they have a responsibility to value the skills that bring their collections to life, and that support is required across the full value chain and fashion community globally. Respect, inclusion, consent, and communication are key to ensure that brands are not diminishing something of intrinsic cultural value when adopting elements from another culture.”

Groups are working hard to address imbalances. The Cultural Intellectual Property Rights Initiative (CIPRI), founded by Monica Moisin, connects designers with traditional textile artisans within a framework that ensures that the artisans’ cultural intellectual property is respected with what CIPRI describes as the “three Cs”: consent, credit, and compensation. Meanwhile, the British Council’s Crafting Futures Community Couture project brings together designers from different cultures to create collaborative garments that can be rented. Digital resources capture the garment’s evolution, making sure its full story, beyond the physical, is told. “This is the future of craft and community, where projects like this allow techniques to evolve and be relevant to new generations in a spirit of equal exchange,” says Blanchard.

Slow fashion label Welana highlights the beauty of Ethiopian artistry – and works alongside the communities that create it (Credit: Welana)

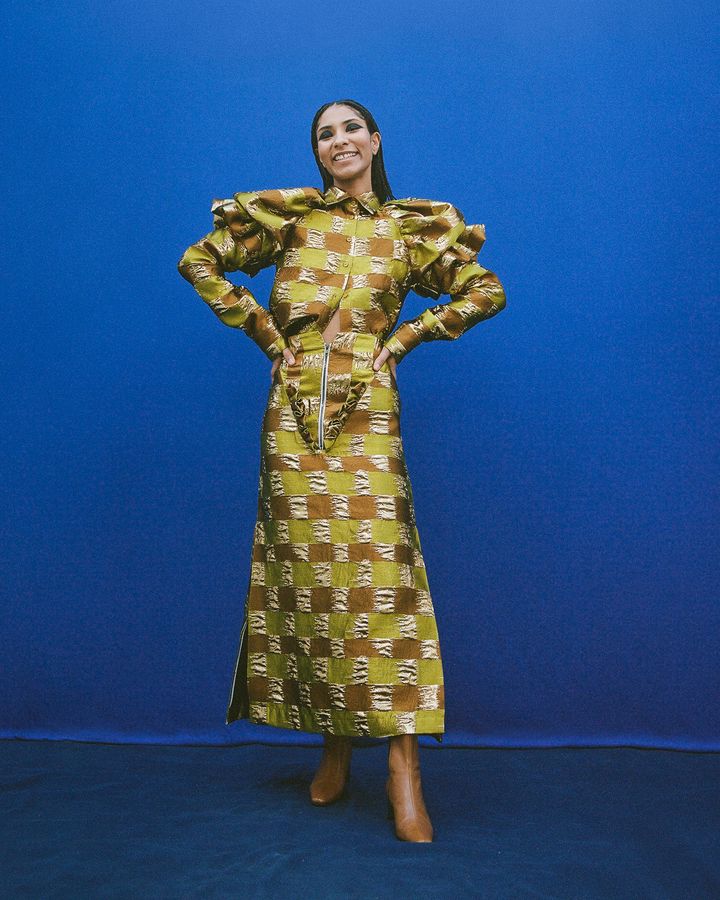

While in an imperfect world, no example is perfect, some designers are coming close. “Indonesian designer Toton Januar, one of the designers in residence at the Biennial, has a very respectful exchange with Indonesian artisans, bringing their craft into contemporary fashion, while their work is fairly compensated,” offers Blanchard. “Through her brand, Anciela, Jennifer Droguett mixes her Colombian heritage and folklore with traditional British tailoring to create her own sartorial language.” Ethiopian fair trade company Sabahar and textile weavers Maraki together source and produce fabrics for slow fashion label Welana, using traditional weaving techniques. “Our whole concept revolves around shining a light on the beauty of Ethiopian artistry, and empowering the community responsible for it,” says Berlin-based co-founder Welella Negussie.

Award-winning Syrian-British designer and course leader at the London College of Fashion, Nabil El Nayal, was invited to develop a new type of embroidery stitch with refugees living in the Za’atari refugee camp, a stitch that would symbolically connect Syria with Za’atari. “All planning including workshops and presentations went out the window as soon as we met the women,” El Nabal told Fashion Trust Arabia. “You have to get good at picking up on the invisible, listening to the inaudible, and seeing solutions to problems as they arise. The women we worked with had the most incredible and diverse range of abilities. We became the students who would go on to learn from them all.” The project aims to help support the development of a self-sustaining business for the women, who have already faced immeasurable challenges.

In 2018, after being granted the Artists International Development Fund by Crafting Futures, artist and textiles designer Ellen Rock was invited to work with the Janakour Women’s Development Centre (JWDC) in Mithila in Nepal, by the foothills of the Himalayas. From the start, her approach was careful and considered, first spending two months as an artist-in-residence, observing and immersing herself in the art, to create a platform of trust and a foundation for collaboration. “I asked the centre what they might like to learn from my practice, what they felt they were missing and what they might like to share with me,” she says. “From this, we developed a workshop plan where we could exchange skills and knowledge which gradually led us to textile development.”

Screen printers printed Rock’s original designs, before the embroiderers and hand painters added detailing on top. “My work focuses on graphic symbols as communication while Mithila art is rooted in cultural identity such as fertility, religion, love – and, more recently, daily activities such as bicycling to work, owning a mobile phone and working as an artist,” says Rock. One of the prints, titled Eye See You features a combined illustration of a daily cycle with Rock’s signature illustrations, integrating Mithila hands – a key motif in Rock’s own work – adorned with tattoos and featuring embroidery interpretation of the print. “Ellen showed us how to apply our designs on to clothes and textiles; she also helped us create a lot of new designs,” says one of the artisans, Madhumala Mandal.

Rock and the artisans spent time thinking about the most beneficial skill that could be exchanged – and that had longevity. “The centre wanted to develop a product, both to apply their designs but also to generate income,” says Rock. “We decided to focus on products, such as embroidered patches or bags, that could be re-produced, not only with our collaborative designs but with original Mithila patterns.” The idea was to create a knowledge transfer that would last long after Rock had left.

Creating bold, graphic prints, Ellen Rock collaborated with Madhumala Mandal and other women hand painters of Mithila, Nepal (Credit: Ellen Rock)

Rock adds: “Appropriation usually involves the removal of origins and heritage, and a re-purposing in a way that only benefits the end company. Without dialogue, this can eradicate ancient wisdom and heritage whilst also removing income streams and livelihoods. A collaboration needs authentic connection, built up over weeks or months. But, I believe that, if designers set measurable impacts which directly involve and consult artisan groups, collaboration can be a powerful tool of amplification and preservation. Ultimately, at the heart of collaboration, is the core belief from both parties that the outcome is stronger.”

For both El Nayal and Rock, cultural collaboration remains a rich source not simply of inspiration, but of equity and global rebalancing. “My approach to fashion is about the collision of cultures, past and present, distant and close. We are living in increasingly polarised times, and my work can speak to that while seeking connections through the medium of fashion; pursuing a highly contemporary outcome, while preserving traditional Syrian dress and textile history,” says El Nayal. “But working with the community needs to be mutually beneficial. I’m keen to protect our combined legacy and cultural identity. Our rich textile culture goes back many centuries, and it’s important to ensure it goes on for many more to come.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.