Why perceptions of tattoos are changing

“When I started out tattoos were seen as something for the outcasts and rebels,” says Dr Woo (real name Brian Woo), a prominent LA-based tattoo artist with 1.8 million Instagram followers and a high-profile clientele that includes Justin Bieber, Miley Cyrus and Drake. “I come from a very traditional immigrant Asian family, so my parents weren’t too buzzed when their son chose this career path.”

More like this:

– The greatest conspiracy in ancient art

– The new generation redefining gender

– What our private scribbles can reveal

Yet 41-year-old Woo, whose prices begin at $2,500 (£2,066), insists body ink no longer carries the same negative connotations. “I get lawyers, doctors, politicians, kids celebrating their 18th birthdays, grandparents… it’s all walks of life coming into my studio,” he explains. “There was a time not too long ago where I was the only one in the room with a tattoo, but in 2022 you’re looked at funny if you don’t have one. Now my parents are okay with this job.”

The designs of tattoo artists like Mister Cartoon (real name Mark Machado) have pushed tattooing forward as an artform (Credit: Mister Cartoon)

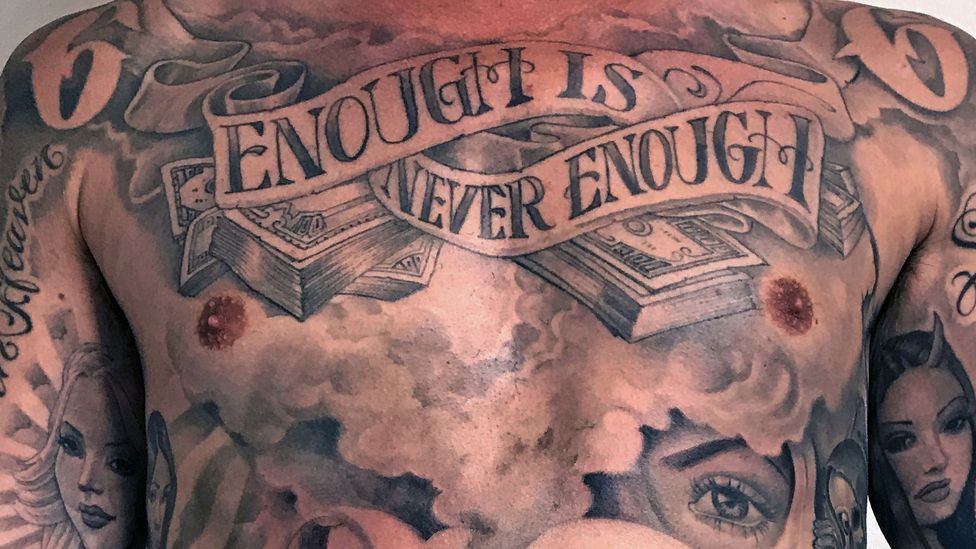

Woo’s comments reflect the cultural ubiquity tattoos are currently enjoying. A 2015 YouGov poll suggested one-fifth of British adults had tattoos, while the most recent figures from Ipsos show that 30% of all Americans have at least one on their bodies (a figure that rises to 40% among the under-35s). What once might have been perceived as a subculture more associated with nomadic sailors and biker gangs than the middle classes is now an omnipresent mainstream force and $3bn-a-year industry.

It seems to be a rite of passage for the world’s biggest pop stars (Post Malone, Billie Eilish) and athletes (LeBron James, Lionel Messi) to have tattoos etched all over their bodies and faces, inspiring fans to do the same. Major fashion houses utilise famous tattooed celebrities to add an edge to their branding (the heavily tatted comedian Pete Davidson is the current global face of H&M); Virgin Atlantic allows staff to proudly show off their sleeves during long-haul flights; and the US army has relaxed historic rules prohibiting visible tattoos on troops, citing “changing social norms” as a reason.

“It’s undeniable how visible tattooing is right now,” explains Matt Lodder, a senior lecturer in Art at the University of Essex who specialises in the history of tattoos. “It is a bigger deal culturally than it’s ever been.”

He continues: “The other day someone sent me an advertising leaflet from the British Post Office, which showed the father of a toddler with a visible full sleeve. There was a time where a relatively conservative organisation like the Post Office doing that would have created a backlash. Now it’s accepted as progressive.”

However, Lodder insists it’s important we frame tattoos as a historic “medium” rather than a “phenomenon”, with the media often downplaying the artform’s heritage by only narrowing in on the buzz of more recent popularity. To truly understand the trajectory of tattoos, he says we must dig deep into the history. “Western tattooing has been a commodity-based art form for only about 140 years,” he explains, suggesting that one of the key drivers behind its commercialisation in the UK was King George V, who got a “desirable” tattoo of a dragon on his arm during a trip to Japan as a teenager in 1881. Conversely, though, he adds, “we also have to remember there’s physical evidence of tattooing that dates all the way back to 3250 BC.”

Ancient roots

Lodder is referring to Ötzi, a European Tyrolean Iceman whose frozen body was preserved beneath an Alpine glacier along the Austrian-Italian border, before finally being discovered by a perplexed German couple 5,300 years later during their walking holiday in the Alps. Ötzi had 61 tattoos across his body, with the tattoos (which were primarily sets of horizontal and vertical lines) thought to have had a therapeutic purpose akin to acupuncture – since they tended to be clustered around Ötzi’s lower back and joints, areas where anthropologists say the Iceman was suffering from degenerative pains and aches.

Other ancient corpses have revealed even more intricate designs. The “Gebelein Man”, who has been on display in the British Museum for more than 100 years, has a tattoo of an interlocking sheep and bull on his arm. The naturally mummified corpse dates back to Ancient Egypt’s Predynastic period around 5,000 years ago, with the tattoos applied permanently under the skin using a carbon-based substance [experts believe it was likely some type of soot]. There’s also evidence that the women of Ancient Egypt had tattoos, with experts speculating that they were carved into the skin so that the gods would protect their babies during pregnancy. The 1891 discovery of Amunet, a priestess of the goddess Hathor at Thebes, showed extensive tattooing across the mummified corpse’s abdominal region.

A heavily-tattooed female warrior priestess dubbed the “Princess of Ukok” was discovered by archaeologists in the Altai Mountains – which run through Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan – back in 1993. The discovery of this 2,500-year-old corpse was particularly significant due to the pristine preservation of the skin and a torso featuring beautifully sophisticated illustrations of mythical beasts, including the antlers of a Capricorn.

Believed to be 25 when she died, the princess was one of the Pazyryks, a Scythian-era tribe that saw body tattoos as a marker of social status, and something that would make it easier for them to be located by loved ones in the afterlife. All these discoveries, according to Lodder, completely shatter the notion that tattooing is somehow a new “trend” – if anything, it is one of the oldest artforms on record.

Maud Wagner was one of the first professional female tattoo artists in the US (Credit: Getty Images)

“The current best evidence suggests tattoos go back 45,000 years,” he adds. “That’s when human beings developed symbolic and communicative visual behaviour. The urge to communicate stories and desires by tattooing something on our skin has long been a basic human need.”

But if tattoos have long been a prized adornment for some, they have also served as a cruel kind of branding. In the ancient Greco-Roman world, tattoos were a mark of punishment and shame, forcibly given to convicts and sex workers. This was a horrific practice that persisted long after the Roman Empire ended, continuing through to America’s slave trade and the Holocaust. But despite this, tattoos simultaneously remained an attractive lure for society’s elite.

The allure of celebrity

In author Margot Mifflin’s brilliant book Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo, she dissects how high society women of the 19th Century in Europe and United States would get tattoos on their feet and upper arms; places easily hidden by clothing. One of the first professional female tattoo artists in the US was Maud Wagner, who learned from her husband, and began work in 1907. Jessie Knight, who started professionally in 1921, was perhaps Wagner’s equivalent in the UK.

For Mifflin, tattoos have always carried counter-culture values for women. “Tattooing meant women could do what they wanted with their own bodies,” she explains. “It was different for women to men, because tattooed women were directly interfering with nature in a way history had previously forbidden. It was a chance for them to rewrite their bodies.”

Mifflin says the “dark shadow” of World War Two – where Jewish prisoners of war were tattooed and numbered by their Nazi capturers during the genocidal murder of the Holocaust – led to a decline in people wanting to get body ink. But by the 1960s, the tide was changing again, something she credits in part to the influence of late rock ‘n’ roll legend Janis Joplin. “Janis had this Florentine bracelet tattooed on her wrist, which was completely visible, and also a heart above her breast,” explains Mifflin.

“She really was this transitional figure who helped tattoos become an alluring mainstream thing. [New York] artist and tattooist Ruth Marten, who blurred the lines between tattoos and the art world, also helped to destroy some of the negative connotations, repositioning tattoos as a rich artform.”

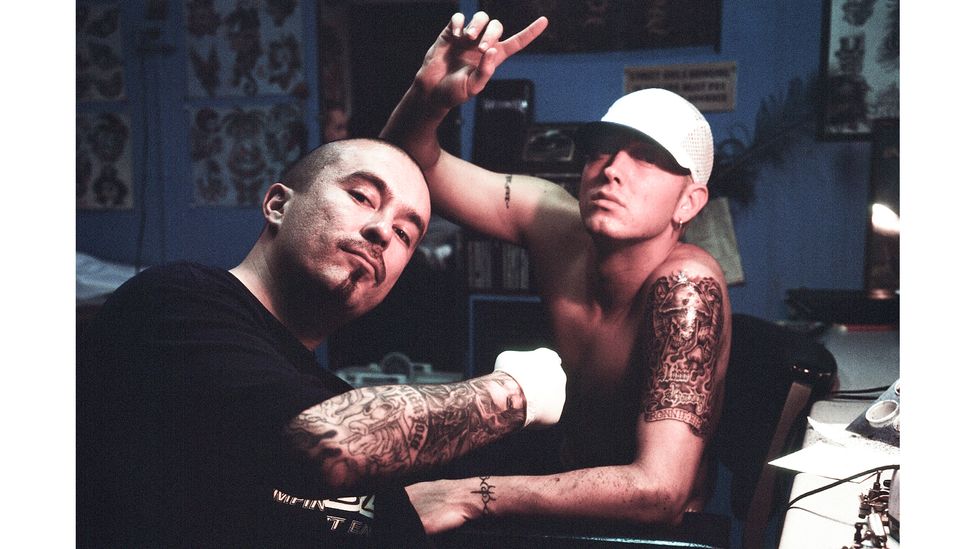

The veteran Mister Cartoon (real name Mark Machado) is one of the greatest living tattoo artists in the US. Working his way up from airbrushing lowrider cars and being a prolific graffiti tagger, the 52-year-old ended up tattooing some of pop culture’s most important names including Beyoncé, Kobe Bryant, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, Dr Dre and 50 Cent. According to Cartoon, although Joplin was indeed a “transitionary” figure, hip-hop culture really helped solidify tattoos as a desirable practice for the masses.

“In my neighbourhood,” the Los Angeles native recalls, “the tattoos you saw were typically done in prison cells. In my mom’s head, she saw those heavily tattooed gangsters as the ones who made us Latinos look bad. But to me, they looked like the coolest people in the world.”

Hip-hop artists including Eminem (here seen getting tattooed by Mister Cartoon) helped solidify the mass popularity of tattoos (Credit: Getty Images)

“When inspiring figures like Eminem, 2Pac, and 50 Cent all got tattoos, the public wanted to follow,” he continues. “All their tattoos were like mirrors to the pop culture, highlighting social issues and inspiring the underdogs to make something of themselves. If a rapper like Gucci Mane got a tattoo on his face, it showed he was all the way in, and that defiance was infectious.”

One of Cartoon’s greatest tattoos is the word “Southside”, which he tatted across rap artist 50 Cent’s back. It is an ode to the rapper’s Southside Queens’ neighbourhood, and it represents how 50’s success meant he was quite literally carrying the hood on his shoulders, and showing anything was possible, even after being shot nine times. Cartoon interprets the Old English lettering aesthetic that he used to see tattooed on LA gang members torsos, and gives it a more grandiose feel by transporting it on to the flesh of a superstar.

“For me it was always about getting the shady type of tattoos from my neighbourhood, which my mom feared were the mark of criminals, and taking them somewhere where they could be seen as luxurious and glamorous,” Cartoon explains. “I wanted to really show their value. My mum is now sitting in a house that tattoos paid for, you know? I feel like I succeeded.”

Fighting against art world snobbery

Despite this rich history, and tattoos’ uniqueness as mobile artworks that walk around with somebody for the whole of their life, Cartoon says he still encounters snobbery. “If you go to art school and say you want to be a tattooist then they still look at it like a dishonest way to make a living,” he says.

“We’re creating art on moving flesh, which requires so much skill, while serving as therapists and marriage councillors to the people who sit in the chair. If you watch someone do a tattoo, and walk away from it thinking it’s not art, then you’re just a crazy art snob.”

Even if snobbery still exists, Mifflin insists the art and tattoo worlds are converging more and more. She credits Mexican tattooist Dr Lakra (who has pioneered a macabre religion-fuelled visual style) and Belgium’s Wim Delvoye (who has controversially tattooed pigs) as two recent figureheads who’ve helped bridge the gap between tattoos and fine art. Lodder, meanwhile, says Japanese tattooist Gakkin is bringing an “avant-garde” edge to the artform.

The major thing that separates the fine art world from the tattooists is the issue of permanence. When a person dies and their body decomposes, so does their tattoo, meaning the original copy of a tattoo artist’s work is lost. By comparison, painters and photographers’ work can live on in galleries, bringing these artists posthumous recognition. For tattooists it’s much more complicated. Infamously, Dr Fukushi Masaichi, a Japanese pathologist who was deemed the “Bodysuit collector”, carried out a project where he kept consenting people’s back skin after they died, preserving their tattoos in Tokyo’s Medical Pathology Museum. But this was a complex process and, understandably, not something that caught on.

Yet renowned New York-based tattoo artist Scott Campbell believes technology can finally help to level the playing field. Alongside LA-based creative agency Cthdrl, he has pioneered the new Scab Shop platform, which allows tattoo artists like Woo and Cartoon to sell their tattoos as NFTs (non-fungible tokens) to the general public, meaning their work can live on in the metaverse, and will no longer die with its owner’s flesh.

It effectively means that a digital replica of a tattoo design is created, which Scab Shop users then have the chance to bid for in an online auction. The NFT also comes with a tattoo appointment, so the winning bidder can then get the virtual design physically inscribed on to their skin. After sale, all the NFT designs remain archived on the Scab Shop portal. The idea is for Scab Shop to be a digital art gallery that preserves tattooists’ work; a Tate Modern for tattooists.

The new art exhibition Tattoo: Art Under the Skin at CaixaForum in Barcelona is testament to the changing perception of tattooing (Credit: CaixaForum Barcelona)

“At the moment, tattoo artists are selling original artwork based on how long it takes to carve onto someone else’s skin,” Campbell tells BBC Culture. “It means we’re selling the hours of our lives more like plumbers and electricians than artists; we’re seen as tradesman who simply carve something on to your arm.”

Campbell claims that if Vincent van Gogh was a tattoo artist, no one would know about his work, “because all of his canvases would have died. Worms would have eaten his art”. With Scab Shop, he insists the work of tattoo artists can finally achieve permanence beyond a mere photographic copy, which, in turn, should help to eradicate some of the snobbery Mister Cartoon alludes to.

“Thanks to Scab Shop, I can sell my original artwork as images, just like an artist might; it really is the first time tattooing can be truly transacted as a traditional art form,” claims Campbell. His hope is this will in turn lead to even more physical exhibitions, like Tattoo: Art Under the Skin, currently running at the CaixaForum in Barcelona, a major historical survey of tattooing from across the world that features, among other things, silicon replicas of body parts on which some of the world’s great tattooists have reproduced their designs.

Yet Lodder is sceptical about tattoos being translated into NFTs, in part because it raises tricky issues around copyright. “The guy who tattooed Mike Tyson’s face sued the people who made The Hangover II movie [in which Tyson appeared] for copyright infringement [after they replicated his tattoo on another character],” says Lodder. “I think the issues around who owns a tattoo, the artist or the person in the chair, aren’t solved by NFTs, but made more complicated.”

Whether Scab Shop proves to be the start of a new era for tattoos or a flash in the pan remains to be seen, but it at least shows tattoo artists are innovating and seeking out new ways to get some of the art world credit that they feel they miss out on.

The gender divide

With the tattoo industry forecast for further growth over the coming three years, Mifflin says ensuring that it’s less male-centric should also be seen as a priority. A 2017 poll by Statista claimed women are more likely to have a tattoo than men. Despite this, only 25% of US tattooists are women, vastly outnumbered by their (75%) male counterparts. “If you read a tattoo magazine, it’s filled with naked female pin-ups,” says Mifflin. “The culture still seems very biased towards men.”

One person with experience of this gender imbalance is Sasha Masiuk, a successful female tattooist who made her name in Russia despite being born in Ukraine. Currently based in Los Angeles, she has five tattoo shops globally. “When I started tattooing clients would meet me in person and be weirded out I was a woman,” she tells the BBC. “It was like I had to go out of my way to prove to them I was as good as a man.”

Yet the fact Masiuk now charges up to $20,000 (£16,534) for her work shows things are changing. She points to shifting attitudes in Russia as proof that tattoo culture isn’t just buoyant in the West, but the East too. “When people saw you had tattoos, you were seen as dangerous or a drug addict,” she reflects of her early career in Russia. “But now in places like St Petersburg and Moscow, tattoos are accepted as a way of life.”

This acceptance is something Masiuk “hopes” will translate into more authoritarian regions of Asia, where tattoos still carry taboo connotations; something illustrated by authorities in Lanzhou, a city in the Gansu province of Northwest China, implementing a tattoo ban for taxi drivers just two years ago on the basis that they “may cause distress to passengers who are women and children”.

A design by Sasha Masiuk, who said she had to deal with sexism when she first entered the industry (Credit: Sasha Masiuk)

It would be dishonest to say that everyone agrees with the late French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss’s notion that “tattoos transform us from raw animals into cooked cultural beings”. In a recent article for The Times, journalist Melanie Phillips wrote that tattoos made her feel “physically sick”, and condemned the contemporary normalisation of the culture, something she suggested was evidence of a “crisis” in moral values.

“There will always be gatekeepers who want to separate tattoos from the institutional fine art world,” counters tattooist Dr Woo. “Will tattoo designs be hanging in the Whitney Museum 400 years from now? That’s left to be said. But history has shown this is an art form that is very resilient.”

If tattoo artists are looking to preserve their work for posterity, tattoo-wearers can get rid of their tattoos more easily than ever. In fact, the tattoo removal devices market has been backed to grow by an “incredible” $245m (£203m) by 2029. “Pretty soon we’re going to be able to just erase and start over,” adds Woo. But what this means for their status as art is another matter.

Even though Woo says the industry is currently a little homogenised with “samey” and “overly simple” Instagram-friendly floral designs, the tattoo titan is convinced his artform will continue to grow globally. He concludes: “Historically, tattoos romanticised the idea of freedom, right? To have one showed you weren’t bound by social standards and could be your own person. They were the mark of the revolutionaries.

“So long as human beings want to feel free, tattoos will live on.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.