5 paintings that show how we really see

A new exhibition about Paul Cézanne at London’s Tate Modern presents an artist who unveiled strange truths about human perception. Cézanne’s paintings astounded his contemporaries. They seemed to offer a radical new way of seeing, even though no one could explain exactly how.

More like this:

– The slave ship in a London courtyard

– The artist who skewers white privilege

– Why 1960 was a turning point for Africa

In 1881, Paul Gauguin joked about how to extract Cézanne’s mysterious methods, instructing Camille Pissarro to “ply him with one of those mysterious homeopathic drugs and come straight to Paris to share the information”. The painter and critic Maurice Denis shared a sense of bewilderment about Cézanne’s revolution in visual representation, writing in 1912 that he had “never heard an admirer… give me a clear and precise account of his admiration.”

The exact nature of Cézanne’s achievement has obsessed many art historians and philosophers over the years. But a critical insight could be found in the field of science. As discoveries by neuroscientists, philosophers, and psychologists have proved, Cézanne’s methods have a curious similarity with the visual processing of the human mind. He overturned centuries of theories about how the eye works by depicting a world constantly in motion, affected by the passing of time and infused with the artist’s own memories and emotions.

Cézanne’s Sugar Bowl, Pears, and Blue Cup (1865-70) is a conventional depiction of a still life (Credit: Alamy)

Cézanne’s insights into human perception took a lifetime of slow experimentation. His early Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup (1865-70), for example, shows Cézanne seeing and painting in a relatively traditional way. Apart from the rougher handling of paint, it is a close relative of traditional scenes like Harmen Steenwyck’s baroque-era Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life from 1640.

At that point, Cézanne’s belief, backed by centuries of scientific theory, was that the eye is exactly like a camera: a gateway for the flow of visual truth that constructs a detailed panorama of our visible environment. This philosophical view is encapsulated in a diagram (made at about the same time as Steenwyck’s painting) from Descartes’s 1637 essay on vision La Dioptrique. It shows the eye receiving a snapshot image from the outside world, which is then understood unambiguously by the brain (represented by the old man at the bottom).

The camera obscura, a device that cast high-focus projections into a sealed box, which had been refined in the 16th and 17th Centuries, seemed to confirm that this was how perception worked.

Still Life with Fruit Dish (1879-80) appears to be painted from a roving gaze, rather than one consistent angle (Credit: Museum of Modern Art)

By the late 1870s, however, Cézanne began questioning that presumption. In Still Life with Fruit Dish (1879-80), the rim of the water-filled glass is shown in a distorted perspective, the background wallpaper appears to be in front of the fruit dish (because the paintwork is more thickly applied), and the white tablecloth feels like it is suspended in space and not draped realistically over the table’s edge. Cézanne is showing us that he doesn’t want to see the scene from one consistent angle, but has embraced a roving gaze, fixating on each element at a time, so that when pieced together we can see the inconsistencies.

This is one of the ways that Cézanne’s approach chimes with what we now know about human visual processing. Although we are scarcely aware of it, our eyes are not static when we look, but are making minuscule darting movements (known as “saccades”) between areas of visual interest. Cézanne’s compartmentalised viewing corresponds with saccade movement. The term “saccades” was first used by Emile Javal after he had discovered the phenomenon at around the same time as Still Life with Fruit Dish was painted: 1878.

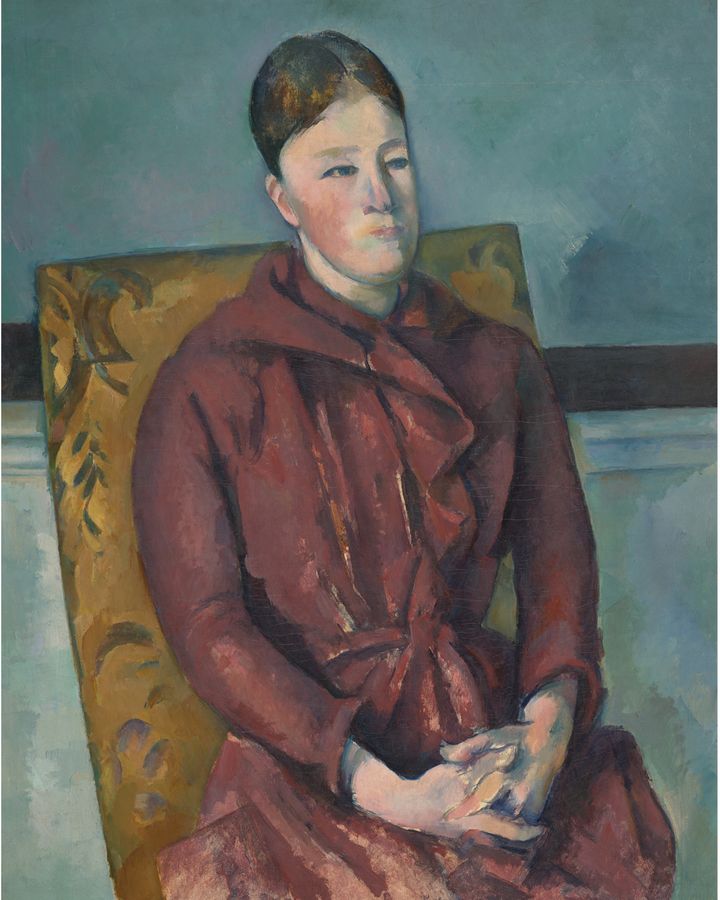

Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair (1888-90) reveals quirks of the human eye, including the ‘Troxler’s fading’ phenomenon (Credit: Art Institute Chicago)

According to the author and poet Joaquim Gasquet, who visited Cézanne in 1897, the artist would spend up to 20 minutes staring fixedly at isolated areas of his subjects whilst painting. Artworks like Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair (1888-90) and Still Life with Fruit Dish show us the visual oddities that this scrutiny produces, which is linked to the anatomy of the human eye and the saccade process.

At the centre of our retinas (the area at the back of the eye) is a small and tightly packed cluster of sensitive “cones” that can perceive colour. Around it are “rods” that can only pick up light and dark. Therefore, the eye can only perceive colour in an absolutely minuscule range – effectively only a few degrees around where we are directly looking. As the eye makes its multiple saccades, the mind is perpetually stitching them together, processing the scattered information to create the illusion of a consistent and seamlessly photo-like reality.

This may seem counterintuitive, but it can be proved. If you fix your eye on a single spot for a long time, your peripheral vision begins to dissolve – a phenomenon known as “Troxler’s Fading“.

A fixed gaze

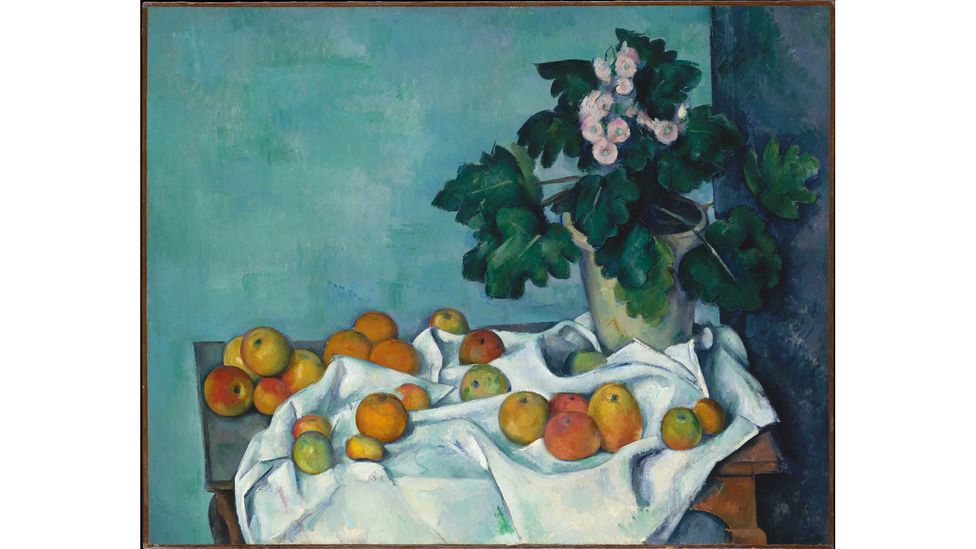

According to Professor Paul Smith of Warwick University, Cézanne’s method of looking with rapt attention at his subjects caused visual anomalies. The sitters in his portraits (such as Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair) seem to have mask-like faces because he concentrated on small areas of facial detail and didn’t allow his mind to consider the face as a holistic whole. In Still Life with Apples and a Pot of Primroses (c 1890), the leaf on the right-hand side doesn’t have a stalk, indicating that an unbroken visual fixation on the area has resulted in Troxler’s Fading.

Still Life with Apples and a Pot of Primroses (c 1890) contains a detail showing what happens when our peripheral vision fades (Credit: Metropolitan Museum)

The fact that he intentionally retained mistakes in his final paintings does not mean that Cézanne was careless. On the contrary, according to Natalia Sidlina, a curator of the Tate Modern exhibition, Cézanne was thoughtful and well-read. “Cézanne translated Latin manuscripts for fun,” she told BBC Culture, “and was friends with some of the leading scientists in fields like natural science, geology and optics”.

One of the most notable developments in science and optics in Cézanne’s lifetime was the invention of photography. We know that Cézanne possessed and even copied photographs. But early cameras like the daguerreotype (invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced to the public in 1839) and the calotype (invented by Henry Fox Talbot and introduced in 1841) replicated the old-fashioned perspective of a static “eye” as conceived by Descartes. They were a disappointment to many 19th-Century painters, including Cézanne, because they conveyed a drab and dispassionate alternative to the world seen through human eyes.

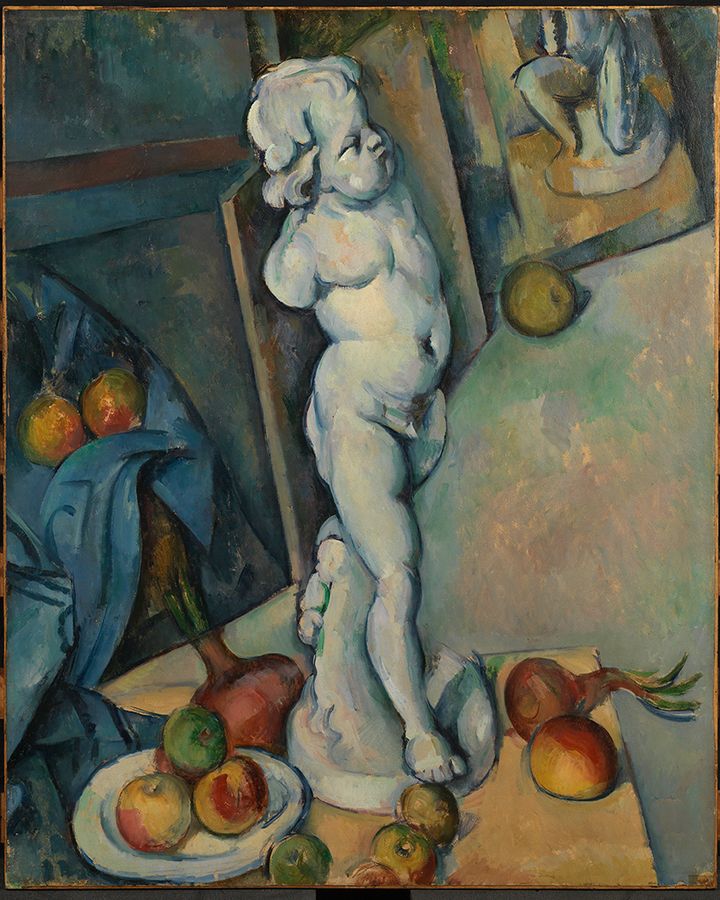

In Still Life with Plaster Cupid (c 1894), Cézanne explored the magic and strangeness of human perception even further. In this Alice-in-Wonderland scene, the space makes no logical sense: the studio floor, depicted on the right-hand side, has a drunken upwards tilt, and the apple at the far edge of the room is the same size as those on the dish in the foreground.

A forerunner of Cubism, Still Life with Plaster Cupid (c 1894) reflects how we see an object over time (Credit: The Courtauld)

If you look closely, you will also notice that Cézanne painted his cupid statuette from various angles – his foot faces us head on, but his hips seem to twist away at 90 degrees as if seen from several viewpoints at once. A conventional still life like Steenwyck’s painting (and Daguerre’s photograph) give us a frozen moment in time. But that view of reality doesn’t tally with embodied experience. Looking is always durational. There’s no such thing as a present, Cézanne tells us – only a continuous flow between past and future.

How we experience time became a main theme in the influential philosophy of Henri Bergson (1859-1941), and in 20th-Century literature, particularly the stream-of-consciousness technique used by TS Eliot, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf.

Cézanne had a direct impact on the development of Cubism, inspiring Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque to incorporate the dimension of time into their work by depicting simultaneous perspectives in a single composition.

Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-6) is an amalgamation of direct observation combined with memory (Credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Helen Tyson Madeira)

In landscapes like Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-6), Cézanne explored how reality is a construct of the mind not the eye. It’s an approach that aligns with the work of 19th-Century scientists like the German physician Hermann von Helmholtz and the English neurologist WJ Dodds, who both showed that vision is not purely optical, but influenced by our memories, appetites and our senses of smell, touch and taste. Cézanne’s deep familiarity with the landscape around the Mont Sainte-Victoire – its rubbly terrain, yearly shifts in colour and various perspectives on the mountain itself indicated by the multiple blue outlines of its profile – have permeated his means of representation.

Cézanne’s achievement, therefore, was to use the act of painting to scrutinise human perception with unprecedented honesty and curiosity. “Cézanne was the midwife of 20th-Century modernist art movements,” Natalia Sidlina summarised. “He put questions at the core of what he was doing, he put the process ahead of the result.”

In doing so he displaced a traditional notion of the eye as a passive “camera” and replaced it with a more nuanced consideration of perception as fallible, mobile, improvisatory, time-based and always inherently embodied. And the more we discover about how the eye interacts with human consciousness, the more Cézanne’s probing, sceptical art makes sense. Perhaps this is why he has continued to be such a compelling figure in the history of art.

Cézanne is at Tate Modern, London, until 12 March 2023.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.