The TV shows struggling for survival

In 1986, 30.1 million people tuned in to watch the Christmas Day instalment of BBC soap EastEnders. The nation was on tenterhooks as “Dirty” Den Watts finally handed over divorce papers to his wife Angie, with the episode drawing higher ratings than The Queen’s Speech.

More like this:

– Why reality TV deserves more credit

– The show that sums up our times

– The 11 best TV shows to watch in October

Now, 36 years since that momentous TV event, and 37 years after EastEnders began, the BBC’s flagship soap is part of the UK’s cultural furniture. Even people who have never watched it can hum its opening theme music. For Britons, it might be hard to imagine that the soap was ever brand new, but, back in the mid-1980s, EastEnders was different from anything viewers had seen before. “It was like watching a documentary. You were a fly on the wall,” Michael Cashman, who played Colin Russell in the soap from 1986 to 1989, tells BBC Culture. “The dialogue was quick and the scenes were fast. There were no lingering shots or long reactions. It was about a community in the East End of London and it moved as sharply or as slowly as their lives.”

General Hospital is one of only three soaps left on terrestrial US TV following the so-called “Soapocalypse” (Credit: ABC)

EastEnders debuted in a crowded field of British soaps: Coronation Street was already 26 years old, while Emmerdale and Brookside were popular too. But in just one year, EastEnders had beaten Coronation Street’s all-time most-viewed episode by 10m viewers. Why was it so popular? “On Coronation Street, the scenes in Rover’s Return had become sedate: nobody passed the camera, there was no background noise, no one was fighting to be heard,” Cashman says. “But in EastEnders there was life. It shook things up and brought Coronation Street back to life too.”

The rivalry between these two soaps endures today, with Coronation Street back on top – for now. But the reality is that Britain is no longer as engaged with the soap genre as it was. Last Christmas, just 2.9 million tuned in for the Christmas Day Eastenders episode, making it only the 10th most-watched programme on Christmas Day overall, where it used to regularly top the ratings. And it’s not just EastEnders: “While TV viewing as a whole fell by 9% between 2017 and 2019, Coronation Street’s audience fell by 19%, while Emmerdale’s went down by 22%,” noted Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian earlier this year.

Soaps aren’t just struggling in the UK. In July, iconic Australian soap Neighbours came to an end after 37 years, when Channel 5 pulled out of the deal to broadcast it in the UK, its biggest market, due to dwindling viewing figures. In South and Central America, where telenovela soap operas reigned supreme for decades and became popular with international viewers too, there are also signs of decline. In 2018, the Wall Street Journal’s David Luhnow and Santiago Pérez wrote that competition from Netflix has prompted Mexican media conglomerate Televisa and other South and Central American broadcasters “to develop real-life, edgier dramas and crime stories to replace the soaps that that once enthralled millions”.

In the US, the field of soaps has narrowed significantly in the last decade, with the cancellation of long-running shows such as All My Children and One Life to Live creating a “Soapocalypse“, as it was dubbed by US media outlets. Now just three soaps – The Bold and the Beautiful, The Young and the Restless, and America’s longest-running soap General Hospital – remain on terrestrial TV, following the move in September of Days of Our Lives to streaming platform Peacock, after dwindling ratings on NBC, so marking the end of an era after its 57 years on the network. So what is driving the decline of soaps? And is there a way back from the brink?

A battle for new audiences

One of soap operas’ major problems in recent times has been a failure to bring in new fans on top of their existing ones. Much of culture right now is preoccupied with nostalgia, from the endless stream of reboots and remakes, to “all stars” reality shows, which bring the most celebrated contestants back onto our screens. Soaps are no exception to this trend: one of the go-to moves for boosting ratings is the return of an iconic character from years gone by. But this doesn’t exactly do much for younger viewers, or anyone who isn’t already familiar with them.

Soaps are struggling to connect with young viewers. In the UK, research conducted by Broadcast Magazine revealed that the number of 16-34 year-olds watching both EastEnders and Coronation Street has more than halved in the last five years. EastEnders’ 16-34 viewership fell from 1.3 million people in 2017 to just 447,000 this year, while Coronation St’s has dropped to 459,000, from 1 million in 2017. This is a problem because, without a new generation of viewers watching soaps, it’s hard to see how they can survive in the long term.

Soaps losing viewers, particularly young people, reflects wider changes in our viewing habits. Many audiences’ first stop when turning on their televisions is now a streaming service, rather than the terrestrial channels on which soaps continue to take pride of place. Most TV can be watched later or recorded, so there is less pressure to watch live. TV journalist Scott Bryan, co-host of BBC 5 Live’s Must Watch podcast, points to a rise in “individual” viewing too. “Ten years ago, it was much more likely that people would watch TV as a family. That is still true for some shows, but I think now we’re much more used to watching shows on individual screens,” he says. “This means that there is less of a tradition in terms of parents watching a soap with their kids and passing that on to them.”

Watched by over 30 million people, the 1986 Christmas Day episode of Eastenders is a shining example of the cultural reach that soaps have had (Credit: Alamy)

In the US, Days of Our Lives moving to Peacock feels like a response to these changes. The streaming platform has more than doubled its audience in the last year and was set up to appeal to a younger viewership than NBC. In the UK, the BBC released episodes of EastEnders on iPlayer during the summer before they were broadcast on terrestrial TV. ITV did the same at Christmas, adding episodes of Coronation Street to ITV Hub – signalling the end of an era where soaps were fearful of “spoilers”. Speaking at the Edinburgh TV festival in August, the BBC’s chief content officer Charlotte Moore reiterated that EastEnders is an “important” title for the BBC and highlighted its potential with young people. “It’s the most popular young audience title we have on iPlayer in terms of the volume of people it brings in every week,” she said. Channel 4 teen soap Hollyoaks, which has turned its fortunes around by the strategic targeting of younger audiences, has gone even further. In 2020, the soap began airing on Snapchat – the most popular social media app with Gen Z users in the UK. “You can lure younger viewers by making TV work around them, rather than having them work around the soap,” Bryan says. Despite being slow on the uptake, soaps are now trying to adapt to the times – and only time will tell whether they are the right fit for streaming-first viewing.

The streaming era has also coincided with the rise of “prestige” television. Soaps used to thrive off a sense of FOMO (fear of missing out), where viewers would feel left out if everyone else seemed to be watching. But from Succession to Game of Thrones and Killing Eve, Big Little Lies and Euphoria, the most talked-about shows are now high-budget spectacles. Amazon’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power is the most expensive TV show ever made, with a budget of £399m for the first season, eclipsing the latest season of Netflix’s Stranger Things, which cost a reported £232 million.

In this new TV environment, episodes are often longer and seasons are shorter, while the actors are frequently Hollywood stars now moving freely between the big and small screen. A limited series like HBO’s Mare of Easttown, starring Academy Award winner Kate Winslet, captivated viewers in 2021 and gave its audience a huge payoff after just seven hour-long episodes – a much smaller time investment than most major soap storylines. “Viewers are now much more used to watching shows with fewer episodes and flipping between shows, rather than sticking with a show for a long period of time,” Bryan says. “And right now, younger viewers maybe aren’t as keen on soaps compared to a very polished, very expensive-looking drama.”

The perception of soaps as “low brow” dates back to the genre’s origins. Soaps became popular in the US before the UK. In fact, the BBC’s first radio soap opera, 1941’s Front Line Family, did not initially air in Britain at all but in North America. The US’s first daytime TV soap opera, These Are My Children, arrived in 1949, followed by Britain’s first TV soap opera, the BBC’s The Grove Family, in 1954. The soap opera form gets its name from the US, where they were produced by companies such as Procter & Gamble, who used them to sell cleaning products, including soap, to a daytime audience of mostly women. US soaps have always been a staple of daytime TV, whereas most soaps in the UK air in the evening. Generally speaking, US soaps tend to be more glossy and “aspirational”, following the lives of wealthier people. British soaps revolve around everyday communities of working and middle-class people, often with a pub as a central fixture. (There are exceptions, like the BBC medical soap Doctors).

Elana Levine, professor of media, cinema and digital studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and author of Her Stories: Daytime Soap Opera and US Television History, tells BBC Culture that the perception of soaps as “low art” is connected to their original association with women. More so than other mediums, soaps have put women in prominent, significant roles and made them central to the narrative. Over the years, Levine says soaps have explored concerns that have been historically associated with women, so there is an element of misogyny in how easily they are deemed frivolous. “Soaps revolve around interpersonal relationships, family, questions of trust and honesty, treasured and private secrets,” she says. “All humans care about those things. But culturally, at least in Western cultures of the 20th Century and beyond, those things have been feminised, meaning they’ve been associated with women.”

Yet the irony is that now it faces a threat from another genre that is also repeatedly, and some would say unfairly, dismissed as lowbrow. Reality TV is often derided despite being one of the most influential genres of the 21st Century. But its unstoppable rise has presented further difficulties for soaps. Reality shows are generally cheap to make by comparison, and a show like Love Island in the UK (which has also spawned a hit US version, screening on Peacock) has managed to bring in millions of viewers every night for many weeks. “Right back to the rise of Big Brother [in the early noughties], reality shows have been able to create national conversations,” Bryan says. “Since then, I think soaps have found it a little bit harder to do that.”

What’s more, “structured” reality shows, like Made in Chelsea in the UK or Bravo’s Real Housewives franchise and Netflix’s Selling Sunset in the US, which follow the lives of wealthy people, brand themselves as “living soap operas”. And in recent years, there has been a noticeable audience crossover: several well-known soap stars, like Lisa Rinna and Eileen Davidson, have joined the Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, while their co-star Erika Jayne landed a recurring role on The Young and the Restless. “Younger viewers who may have watched soap operas can get some of those same pleasures and enjoyment through reality TV,” says Levine. “Reality shows being similar to soap operas is part of what has allowed for their success. But it’s also made soap operas less prominent and secure as a cultural form.”

Losing the plot

Added to that, there’s a question around whether soaps, in trying too hard to snare audiences’ attention, have in fact lost something of what made them special. There has been a long tradition of soaps tackling social issues, ahead of other mediums. In the UK, the first same-sex kisses on TV, between two men and two women, were both in soaps: EastEnders in 1989 followed by Brookside in 1994. Alongside Nicholas Donovan, Cashman was one half of the first gay kiss on British TV. The scene provoked a tabloid backlash, including a notorious article written in The Sun by Piers Morgan.

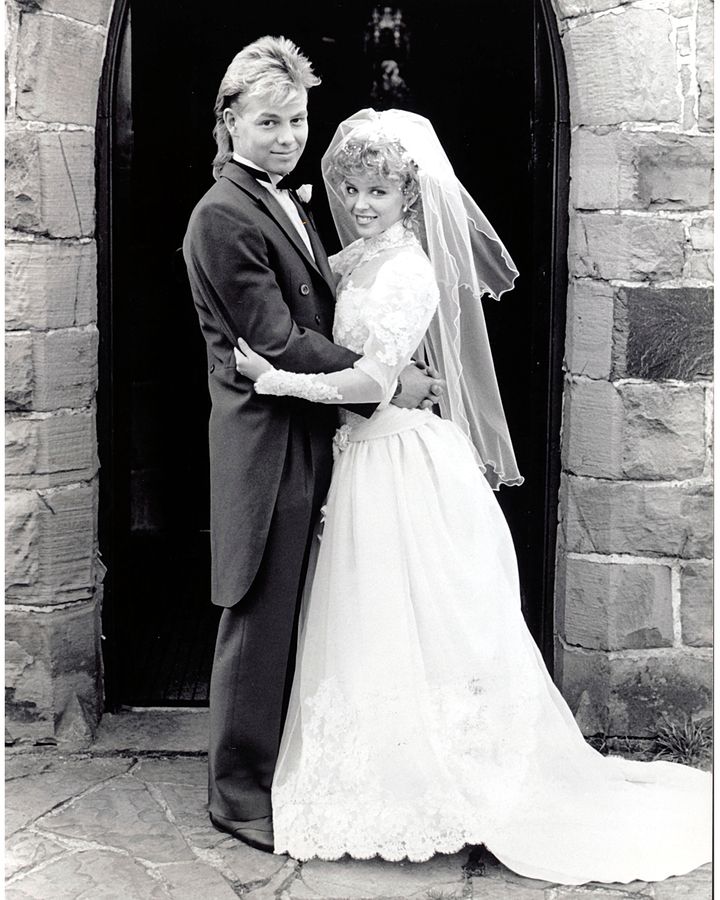

Australian soap Neighbours ended in July after 37 years on air, having launched the careers of Kylie Minogue and Margot Robbie among others (Credit: Getty Images)

Despite reactions like this, though, Cashman says that Eastenders never set out to create controversy, but rather deal with things going on in society with sincerity and credibility. “EastEnders followed issues that people who lived on the square would experience,” he says. “The gentrification of parts of the East End of London, with the so-called ‘yuppies’ moving in, was something people were going through at that time.” Cashman thinks the relationship between his character Colin and his first romantic interest on the square, Barry Clark (Gary Halles), worked because Colin was an interloper into the square and Barry was a local market trader. As the relationship progressed, the characters, as gay men during the Aids crisis, also became a prism through which audiences could learn about the stigma and misinformation surrounding the disease. “That was a brilliant reflection of issues sitting comfortably and appropriately within a community, rather than imposed,” he says.

In the US, Levine says that a “direct engagement” with social issues became increasingly significant in soap starting in the 1960s and peaking in the 1990s. “Women’s issues are probably the most consistently dealt with – things like abortion and rape, which weren’t always getting attention elsewhere in entertainment media,” she says. “Soaps could get away with this because, really, they knew people weren’t paying as much attention to them.” In 1973, All My Children’s Erica Kane (Susan Lucci) had US daytime TV’s first legal abortion. The storyline was a groundbreaking moment for US TV, particularly because her reasoning was that she simply didn’t want to have a child. When it comes to same-sex relationships, Levine thinks that US soaps have not been as pioneering, perhaps because a daytime TV audience was presumed to be less interested in them. “Same-sex relationships is one area where I would say American soaps have not been as cutting edge, when compared with other forms of television,” she says. “Same-sex relationships didn’t become a part of soaps until the 2000s, by which point there were already others on primetime TV.”

But soap storylines have become gradually more sensationalist over the years. Today, a divorce would probably be deemed rather tame, particularly for a box-office Christmas episode, in an era when explosions, shootings, murders and a whole range of dramatic twists are now commonplace. Emmerdale’s Christmas special in 1993, where a plane crashed into the fictional village of Beckindale, was a key moment of change. It reset the show, destroying the original village and killing off multiple main characters, and remains the soap’s highest-rated episode ever, with 18 million people tuning in, so it clearly worked in the short-term. But over time, the ante has been gradually raised on soaps, and the long-term effect has been corrosive, with no shortage of storylines that are ludicrous at best and damaging at worst.

Looking back to the origin of EastEnders, Cashman says its appeal was grounded in the realism of the characters, who would have “run a mile” rather than been anywhere near many situations we see in soaps today. “The whole thing was character-led and not driven by plot, or story or an imposed set of circumstances. Nothing would have worked if the characters were not believable or recognisable,” he says. He remembers showrunner Julia Smith coming into the makeup room and asking for excessive makeup to be removed, because she wanted the actors to resemble an actual working-class community. Everyday people, not melodramatic storylines, were the main draw. “Anyone coming in to work on EastEnders today should have to watch episodes from the first three years,” he says. “Because it set the tone by which the notion became gripped.”

Soaps can stiil have a valuable function in highlighting social issues. Hollyoaks is a soap that has been particularly strong in this respect, exploring everything from eating disorders to the rise of the far right, domestic violence to online trolling and addiction, and working with charities to ensure that storylines are handled sensitively. However, even then, its choice of what to focus on can feel a bit contrived, as if the direction of characters has been dictated by which topics are trending on social media. And with so many other places to find information about topical issues these days, it’s unlikely that soaps are the main source of information, like they might have been in the past – for young viewers in particular

Is there a future for soaps?

Part of the difficulty soaps face is that their decline isn’t down to any one factor. It’s a combination of audiences gravitating towards different genres of TV, as well as the proliferation of other ways of watching it. But all might not be lost. “I wasn’t sure what was going to happen with American soaps [and] if they were going to survive,” Levine says. “But at least for now, there is enough there to sustain a smaller soap opera world. It’s a form that has lasted for so long that I don’t think it’s going to ever fully disappear.”

“Living soap operas” like The Real Housewives of Beverley Hills have threatened to eclipse fictional soaps with their glitzy melodrama (Credit: Alamy)

It seems as though there is a future for soaps – albeit a smaller one, without the tens of millions of viewers they once pulled in. In the UK, the BBC spent £87m on a new set for EastEnders in 2019 and, in March this year, ITV announced that construction work has started on an expansion of the Coronation Street set. Such investments do not suggest that these shows will be leaving our screens anytime soon. And while soap audiences are in decline, the numbers are not insignificant: Emmerdale isn’t generating as many tweets, news stories and think-pieces as a show like Love Island, but this summer it still pulled in similar ratings.

Bryan thinks there is a future for the soaps that can adapt to these new times. “I wouldn’t write soaps off entirely,” he says, explaining that the cancellation of Neighbours was a “wake-up call” to the rest of the field. “You always assume that soaps will continue forever and that the shows you’ve always watched will always be there, but now I feel that there’s now a renewed effort to put some energy back into the soaps, because if they slip away, then everyone loses out.”

With so much of our lives now online, perhaps we also don’t relate as strongly to the idea of “community” in a physical sense. The feeling of normality and the pub setting is where most UK soaps are grounded, so a shift away from that might hurt them more than their US counterparts, which have traded on a more escapist element. But the recent outpourings of grief at the passing of British soap legends June Brown and Barbara Windsor suggest that a love for some characters still brings people together. And that feeling of community could be even more valuable today, when it feels in such short supply in our everyday lives.

In some ways, soaps have been a victim of their own success, inspiring other genres like reality TV, which trade on a similar appeal. They are also the place where we first saw the stars of tomorrow, like Margot Robbie, Nathalie Emmanuel, Liam Hemsworth, Kylie Minogue and Sarah Michelle Gellar – and so the disappearance of these key training grounds for talent could be significant. But the cultural loss of them runs much deeper than that. Reflecting on the heyday of British soaps, Cashman says there was a “degree of certainty” in tuning into a world that felt like it would never end, with characters who would be there forever. “I remember being 10 years old, and hearing the trumpets of the theme tune of Coronation Street starting. I would run across the council buildings to get home,” he says. “You would hear it coming out of people’s houses, like it was calling you home.” And soap operas still have the ability to provide us with that unique sense of continuity and reassurance – should we, as audiences, want it.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.