Sex, violence and sparkling one-liners

When you hear the words Noël Coward, they probably conjure a certain idea: an elegant, well-spoken English gentleman, in a dressing gown, waving a cigarette holder or a glass of champagne, dripping acerbic little one-liners. Maybe you know his songs – from comic ditties like Mad Dogs and Englishmen to songbook classics like Mad About the Boy. Or his plays, those witty, sparkling comedies still considered box-office gold, like Private Lives, Hay Fever and Blithe Spirit.

More like this:

– The classic musical that’s really about sex and death

– Britain’s most scandalous family

– The bohemians who shocked Victorian Britain

2023 marks 50 years since Coward’s death, but while his influence and popularity endures, is it possible that we’re misremembering the man who earned the nickname “The Master”? Could it be that the image of him that lives on is mere grinning caricature, and gets in the way of really understanding his work? Both a new biography and documentary film seem to think so, aiming to reveal the darkness, the complexity and the radicalness of Coward – as have two recent productions that leaned into the thornier aspects of his plays.

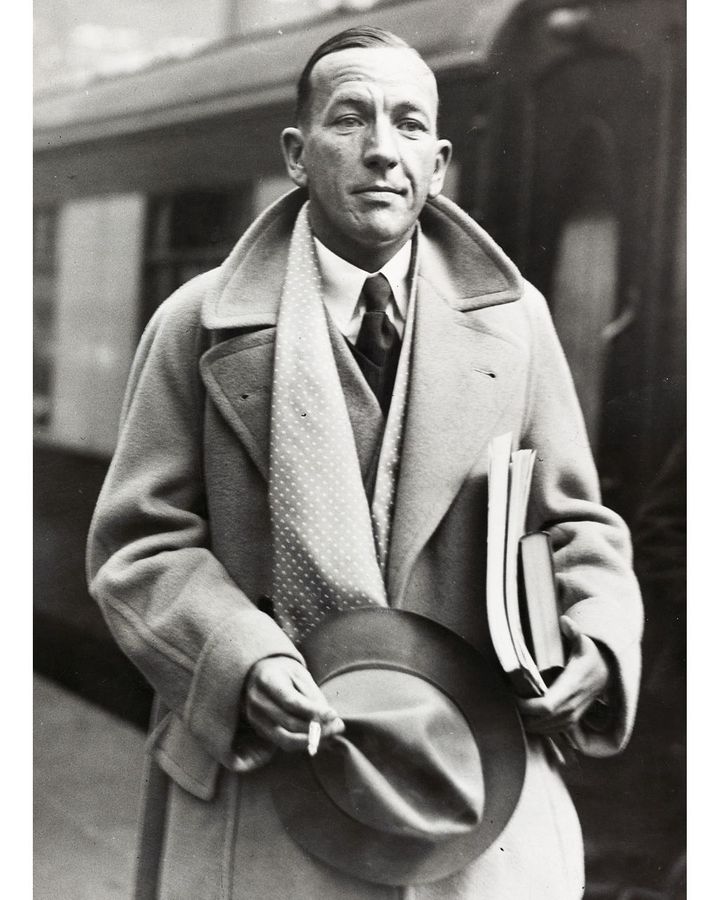

Coward had a long and glittering career, which took him from 1920s London all the way to Las Vegas (Credit: Noel Coward Archive Trust)

Coward had a front-row seat for much of the 20th Century: both its traumas and its thrills. Born in 1899, he was young enough to be called up for World War One, and to not only be one of the Bright Young Things – the nickname given to the wild-living, press-friendly socialites who dazzled 1920s London – but to write many of the defining shows about them. During World War Two, he worked as a spy, as well as singing for the troops and making hugely popular war movies. When his work fell out of fashion in the UK, he was warmly embraced as a cabaret act in mid-century America, first on stage in Las Vegas and then on television. Finally, a series of starry revivals on both sides of the Atlantic canonised his plays in the 1960s, cementing his status as a national treasure.

And he was insanely prolific, writing hundreds of songs, some 50 published plays and 40 more unpublished ones, points out Oliver Soden, author of Masquerade: The Lives of Noel Coward. It was reading all the plays during lockdown that convinced the author that there was still much to discover in Coward’s work.

“Obviously they are very funny, but what surprised me was how much more than ‘just’ funny they are,” he tells BBC Culture. “Page after page of really surprisingly truthful things to say about sex and class and love and how to live. And a deep seam of bitterness and passion and cynicism.”

Sex, drugs and violence

It is these darker aspects that have been brought to the fore in two recent British revivals. At London’s Donmar Warehouse, Michael Longhurst’s production of Private Lives, about tempestuous former lovers whose passion re-ignites when they happen to honeymoon with new spouses at the same hotel, didn’t shy away from the violence – spoken and physical – that’s in the text. Admittedly, any good production will be alive to this, but the refusal to let the characters off the hook made it very bleak at times: Amanda and Elyot emerged as damaged individuals who inflict real harm, rather than merely reckless romantics.

Meanwhile The Vortex, Coward’s breakthrough 1924 play, enjoyed a rarer revival at Chichester Festival Theatre. It concerns Florence, an aging beauty having an affair with a much younger man, who runs off with her son Nicky’s fiancée; the play features cocaine addiction, hints of homosexuality and much adultery. The writing can be startlingly raw – not a quality one usually associates with Coward, but something Daniel Raggett’s production embraced, gradually stripping away the furniture and fripperies of a country house party until Florence and Nicky were tearing each other apart on an empty stage. It struck me as a missing step between the late 18th-Century tragedies of Ibsen, and Tennessee Williams’s mid-century masterpieces.

While its depictions of sex ‘n’ drugs sound rather moralising now, at its premiere The Vortex – which Coward starred in, as with many of his plays – scandalised audiences. “There is a touch of genius here,” wrote The Telegraph. “But its power is of a diseased kind.” As with much of Coward’s work, there is stealth radicalness in its centring of female sexual appetites, its hints of same-sex attraction, and its skewering of both stifling social convention and decadent bohemian excess.

“Coward is one of the chief architects, in the theatre at least, of the new century: trying to throw out the conventions of a previous age, and work out new ways of living… with your own gender, or in twos or threes or fours,” says Soden. “But he is attuned to how difficult it is to do that: it isn’t just a case of ‘oh we’re all free and easy now’. It’s really hard to be free, and it’s really hard to be true to yourself.”

The recent revival of Private Lives at London’s Donmar Warehouse foregrounded its violence (Credit: Marc Brenner)

Both these productions delivered the delicious waspishness we expect of Coward’s depictions of high-society partying and moral flippancy – but they also brought out the terror that there might be nothing beyond all that. The fear that love might be impossible and life pointless lurks in many of Coward’s plays, and indeed throughout his own life.

While he honed to perfection the persona of “comic genius Noël Coward”, behind the mask was a man who suffered nervous breakdowns, depressions and crying fits; who feared the loss of control that came with falling in love, and had troubled relationships; whose punishing work schedule and relentless appetite for travel suggest someone almost on the run from themselves. The US actress Elaine Stritch, in a letter to mutual friends in 1951, described Coward as “one of the saddest men I’ve ever known”.

“The exhausting thing [for him was] having to perform Noël Coward all the time,” suggests Barnaby Thompson, director of the documentary Mad About the Boy. “I assumed he grew up in a nice family, had a good education… then we find out he left school at nine? He was a child actor, and entirely self-educated. So you’ve got a guy who, from nowhere, created this incredible persona that ended up defining the modern Englishman.”

And maintaining this fiction clearly took a toll: Coward glossed over many aspects of his life, from his lower middle-class upbringing (his father was a travelling piano salesman) to his lack of Oxbridge education to how hard he worked. He preferred to give the impression of effortless success.

Then, of course, there was his sexuality. Coward did have long-term partners – his first, rather toxic relationship was in 1925 with Jack Wilson, who became his manager in part to account for why they spent so much time together; his most significant was the actor Graham Payn, who was with Coward for three decades before his death. In between – and indeed during – these relationships, there were many other lovers, including a wartime affair with Michael Redgrave and a fling with Gore Vidal.

But while friends all knew that Coward was gay, it wasn’t possible to be publicly out for most of his career: homosexuality was illegal in Britain until five years before Coward’s death in 1973. Although earlier plays are sometimes remarkably candid – Design for Living from 1932 is about a bisexual love triangle – in the more censorious 1950s, Coward was shaken when his friend (and former understudy) John Gielgud was arrested in a public toilet. Coward’s sexuality may have even been why Winston Churchill blocked a recommendation from King George VI, no less, that Coward should be given a knighthood in 1942. He’d have to wait till 1970.

“All that does mean that even though you are the most successful person in the world, you never rest easy,” posits Thompson. “I think he felt like an outsider more or less his whole life.”

Coward’s out-sized, charming persona was his passport to freely moving through worlds he was not from. It has not, however, necessarily helped our understanding of the work: it’s taken “half a century to get him out the way!” Soden laughs. Coward had a vein of determined anti-intellectualism, and often undermined his own work: “He would swear blind that he wasn’t remotely serious, just a silly trite little comedian. But the plays tell a completely different story, whether or not he meant them to,” insists Soden.

Coward “wraps this flippant humour around himself like a shield – it’s not only disguise but protection,” he adds. And when you look at Coward’s early years, you see why he might want that armour: they are ripe with grief and guilt.

His troubled start

From the age of 14, he had some sort of relationship with 36-year-old artist, Philip Streatfeild – possibly sexual – before Streatfeild died of trench fever in World War One. Coward’s other close friend, John Ekins, also died in the war. In 1918, at the age of 18, Coward had a nervous breakdown in an army training camp before seeing any action, and was hospitalised for six weeks.

“Coward is of the generation that came out of the First World War and the global pandemic of the Spanish Flu, and thought that the future was deeply bleak, with another war on the horizon,” says Soden.

How to deal with this bleakness? Sing and dance and laugh through it. Make-believe had always been Coward’s escape: he’d been acting professionally from the age of 10, and even as a teenager was churning out plays and songs and novels. Boundless ambition was matched by determined graft.

Coward wrote one of cinema’s all-time great romances, 1942’s Brief Encounter (Credit: Alamy)

“He’s spat out into the 1920s with this hole at the centre of his life which only fame and success can adequately fill,” says Soden. “It’s as if there can never be too much of it.” And soon, there really was silly amounts. By 25, Coward was “more famous than the prime minister,” says Soden, with four plays on in London in June 1925. He stormed the US, opening three plays on Broadway by the end of the year: The Vortex, Hay Fever, and Easy Virtue – the latter featuring another woman frank about her enjoyment of sex, and stifled by the disapproving and hypocritical upper-classes.

By 1926, 3,000 productions of Coward’s plays had been staged worldwide, and his annual income was estimated to be at least £50,000 (£15 million today). He had become the highest paid writer in the world, but the relentless schedule soon took its toll. In autumn 1926, Coward found himself unable to stop crying during a performance and collapsed in his dressing room afterwards.

While wary of offering posthumous diagnoses, Soden tentatively suggests that Coward may have had bipolar disorder. What is clear is that his life was marked by periods of “astonishingly manic activity, rehearsing nine to five, a show an evening, partying till 2am… and then he crumbles.”

A pattern emerged where he would work intensely, and then flit off on travels – sometimes with friends and lovers, often alone, visiting everywhere from Mongolia to Argentina, before living in Jamaica and Switzerland (yes, dodging taxes) later in life. But it also seems he took comfort in the act of travelling itself. “He used movement as a way of dealing with pain,” suggests Thompson.

When World War Two began, the deeply patriotic Coward attempted to atone for missing the first one – bothering everyone, up to and including Churchill, for a job. He ended up with several: spying for an underground new secret service, running a propaganda department in France, attempting to stealthily influence important Americans to support Britain and enter the war, even holding meetings in President Roosevelt’s bedroom.

It may have been his greatest role – all that mask wearing proving excellent practice for going undercover. The fact that no-one took him seriously was his “best qualification for being a spy,” says Soden. But Coward was, arguably, too convincing: the press disparaged him for apparently jollying about in America while everyone else suffered, while his international playboy status was frequently seen as a liability by politicians. Both reactions deeply hurt Coward; war service was one area of life where he desperately wanted to be taken seriously.

In fact, some of his greatest achievements lay in the stories he told during the conflict. Coward penned the script for one of the most moving films ever made, Brief Encounter; scripted, co-directed and starred in the earnestly patriotic megahit In Which We Serve, and wrote one of his most enduring stage comedies, Blithe Spirit, about a writer plagued by ghosts of his dead wives.

In Blithe Spirit, Coward played a middle-aged novelist accused of “nauseating” flippancy. It may have been a savage self-portrait – and his next role, a self-obsessed, egotistical actor in Present Laughter in 1942, was certainly the height of Coward-sending-up-Coward.

The Master may have hidden always behind a mask, but he was also hiding in plain sight – continually using his plays to remind audiences of the roles he played, the masks he wore. Consider this line from Leo, another character close to a self-portrait, in Design for Living: “It’s all a question of masks, really… we all wear them as a form of protection; modern life forces us to.” Fifty years since his death, we still enjoy Coward’s wit and humour – but are maybe still uncovering the sadness that lies beneath.

Masquerade by Oliver Soden is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson; Mad About the Boy is out now.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.